Research Outputs

Publications, articles under review, and special issue volumes accepted

Gibson (2022). Data-Driven Campaigning as a Disruptive Force

Gibson, R. “Data-Driven Campaigning as a Disruptive Force” 2022. Political Communication, Forum section of Special issue on Digital Campaigning in Dissonant Public Spheres. (Eds. K. Koc Michalska, U. Klinger, A. Rommele and L. Bennett.)

Concern about whether contemporary societies face a ‘crisis of democracy’ has grown in recent years (Kriesi, 2020). While the severity of the malaise may be disputed there is growing suspicion that the increasing reliance of political actors on digital technology and particularly new ‘data driven’ campaign techniques may be contributing to growth in citizen disengagement and discontent (Bennett and Lyon, 2019). The grounds for this claim are essentially three-fold. First, data-driven campaigns promote a more individualized form of political targeting that allows parties to narrow their appeals to the most persuadable and ‘perceived’ sections of the electorate (Hersh, 2015), and thereby effectively bypass those harder to reach groups of under-mobilized voters, i.e. the young, the disinterested, and the marginalized. Furthermore, through these micro-targeting techniques, campaigners can more accurately target demobilizing messages at opposition supporters to dissuade them from turning out. Second, social media platforms provide powerful new channels for the release of automated, anonymized, false information or ‘computational propaganda’ by rogue actors, both foreign and domestic. These disinformation campaigns are explicitly designed to mislead and confuse voters, and are escalating in scale and sophistication (Woolley and Howard, 2018). Finally, campaigns themselves are now increasingly reliant on the ‘wisdom’ of AI and computer modelling for basic tasks such as resource allocation and message construction. This shift creates a new technological elite at the heart of campaigns that operate in an opaque and unaccountable manner (Tufecki, 2014). The combined impact of these developments is a further shrinking of the public sphere and decline in the representativeness and accountability of democratic institutions. Voters who do actually make it the polls, face the increasingly difficult task of making an informed choice, as they struggle to discern both the accuracy and source of the political content they encounter online. Given the potentially serious harms that DDC presents to democracy, systematic investigation of its adoption and usage across countries is now a priority for academic research. This is precisely the goal of a new ERC funded project, Digital Campaigning and Electoral Democracy (DiCED). In this short essay we highlight in brief, the key questions the project will pursue and that we urge the wider literature to explore.

Dommett, K., Barclay, A., and R. Gibson [Under review]. Just what is data-driven campaigning? A systematic review

Dommett, K. Barclay A. and R. Gibson (2021) “Just what is data-driven campaigning? A systematic review.” Under review, Information Communication and Society

The idea of data-driven campaigning has gained increased prominence in recent years. Often associated with the practices of Cambridge Analytica and linked to debates about the health of modern democracy, scholars have devoted much attention to the rise of data-driven politics. Primarily focused on practice in the US, to date few scholars have made efforts to define the precise meaning of ‘data-driven campaigning’. With growing recognition that data-driven campaigning can take different forms dependent on context and available resource, new questions have emerged as to exactly what is indicative of this phenomena. In this piece we systematically review existing discussions of data-driven campaigning to unpack the components of this idea. Identifying areas of convergence and divergence in existing discussions of ‘data’, ‘driven’, and ‘campaigning’, we classify existing debate to highlight universal and particular attributes of this activity. This article accordingly provides the first comprehensive definition of data-driven campaigning, and aims to facilitate international study of this activity.

Gibson, R., Bon, E. and K. Dommett. [Submission Pending]. I always feel like somebody’s watching me”: What do the U.S. electorate know about political micro-targeting and how much do they care?”

Gibson, R., Bon, E. and K. Dommett. “I always feel like somebody’s watching me”: What do the U.S. electorate know about political micro-targeting and how much do they care?” (APSA paper 2021) Abstract accepted for submission. Journal of Quantitative Description: Digital Media. Submission pending

The practice of political micro-targeting (PMT) – tailoring messages for voters based on their personal data – has increased significantly over the past two decades, particularly in the U.S. Studies of PMT have typically concentrated on measuring its impact on voters’ behaviour and attitudes, or assessing its broader consequences for democracy. Less attention has been given to basic descriptive questions such as how much people know and care about PMT, and whether and how this varies within the electorate. This paper addresses this gap by reporting the findings from an online survey (weighted to be nationally representative on age, gender, ethnicity, region and past vote), that included items tapping attitudes toward PMT during the 2020 U.S. Presidential campaign. Specifically we measure levels of awareness, aversion, knowledge, and concern about PMT, and how this varies at the individual level. For the latter analysis, we demonstrate the relevance of a new set of psychological and personality traits as moderators of these attitudes, and recommend that future causal analyses incorporate these factors when theorizing and modelling voter responses to PMT.

Gibson, R., Bon, E., Darius, P., J. Nagler, and Smyth, P. [Decision Pending] Traditional versus New Sources of Political (Dis)Engagement? Unpacking the Effect of Different Types of Twitter Campaigning on Voter Attitudes and Behavior in the 2020 US Presidential Election

Gibson, R., Bon, E., Darius, P., J. Nagler, and Smyth, P. “Traditional versus New Sources of Political (Dis)Engagement? Unpacking the Effect of Different Types of Twitter Campaigning on Voter Attitudes and Behavior in the 2020 US Presidential Election “Abstract submitted to Media and Communication. (Decision pending)

Social media campaigning is increasingly linked with anti-democratic outcomes including declines in voter knowledge, turnout and trust. Concern to date has focused largely on the impact of Facebook adverts (Borgesius et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2018), leaving the impact of ‘organic’ social media campaigning by candidates and non-official political ‘influencers’ less well studied. This ‘softer’ form of campaigning arguably constitutes an equally important, if more subtle influence on voters. This study will investigate the effects of softer type of social media campaigning on voter behavior using Twitter data from the 2020 U.S. Presidential election campaign. Twitter is a valuable platform to assess this mode of campaign communication given it banned political ads from late 2019. Specifically, we compare the impact of exposure to three different types of actor – official campaigns, media and informal political influencers – on participation and trust in political institutions, the electoral system, and the information presented by campaigns. As well as designing an innovative measure of political influencers we develop hypotheses about the size and direction of effects of each campaign actor, and the moderating effects of ideology. In particular, we expect greater exposure to right-wing campaign content reduces political trust, particularly in the electoral system. We test our expectations using an innovative dataset that combines individuals (n= 697) Twitter feeds with their responses to a two-wave pre- and post-election online panel survey fielded by YouGov.

Gibson, R. and T. Buskirk. [Under review] New Sources of Data: New Methodological Choices and Challenges

”New Sources of Data: New Methodological Choices and Challenges” Special Issue proposal prepared for submission to methods, data, analysis. (Eds.) Gibson, R. and T. Buskirk. (Under review)

This focus of this proposed Special Issue of Methods, data, analyses (mda) is to promote more reflection on, and exchange of, emerging best practices in the collection, analysis and sharing of new data sources among Social Scientists. This topic is of growing importance for quantitative social science given that social media and digital trace data as well as data collected from sensors are now widely used in many areas of research. The appeal of these data is evident based on their sheer volume, and the extent to which they unlock new research questions, offer fresh insight into perennial problems, and also provide access to ‘harder to reach’ geographies and populations. On the more negative side, social media data, in particular, are often themselves hard to obtain, in that they sit behind paywalls or tech company restrictions (boyd, 2015). Once obtained they can be highly selective and unrepresentative of target populations, with bias levels difficult if not impossible to ascertain. They also invariably carry significant ‘noise’ and require an extensive amount of cleaning and validation before they are ready for use. Even with the most intensive of ‘housekeeping’ efforts, the data still come with the caveat that they are the product of unknown internal algorithms, making inference about exposure and impact an even more difficult task than is the case for ‘standard’ media content.

Given both the merits and these known and unknown problems in the collection and analysis of many types of new and emerging data sources, there is now an increasing need for academia to openly confront and interrogate the assumptions and processes followed in working with them. The recognition that social media and digital trace data, for example, have properties that deviate from the ‘norm’, both in regard to their basic format, underlying (lack of) structure, and representativeness, is becoming more common across the discipline (Amaya, 2021; Conrad et al., 2021; Buskirk & Kirchner, 2020). In this special issue we aim to build on this growing trend toward an ‘open research’ culture around the challenges of working with social media data. Specifically, we will highlight and showcase work that explicitly documents how research practices have been reviewed, adjusted, and updated to accommodate the unexpected demands presented by social media data and provide as robust as basis as possible for scientific analysis. Of particular interest will be papers that focus on detailing the methodological pathway and course of decision-making involved in implementing a research design that is reliant on one or many new or emerging data sources like digital trace data , social media data or sensor data, for example for its conclusions. Given the interests of mda, we especially invite authors to submit articles extending the profession’s knowledge on the opportunities and problems involved in linking social media, digital trace or sensor data, for example, to other types of data such as that generated through surveys, as well as administrative data, such as census or electoral roll information. It may focus on a single research paper or a particular element of the longer research process, collection, analysis, or issues around data sharing and collaboration..

Our goal is to provide offer a new resource for scholars that will present a range of ‘lessons learned’ and best practice to guide others in the design of more robust approaches to the use of social media data. We envisage a collection of papers that constitute a ‘must read’ for those seeking to conduct a project that uses any type of social media data. The volume itself, and the approach of ‘reflexive praxis’ that it encourages would constitute an innovative and even pioneering contribution to knowledge production and particularly open research. Authors would be encouraged to openly discuss the problems and critical decisions they faced in generating meaningful findings from new forms of ‘big’ data. As such we would expect the journal to be of widespread multi-disciplinary relevance and high impact.

Gibson, R., Rommele, A., and E. Bon. [Under review]. Operationalising Data-Driven Campaigning: Designing a New Tool for Mapping and Guiding Regulatory Intervention

Gibson, R. Rommele, A. and E. Bon. “Operationalising Data-Driven Campaigning: Designing a New Tool for Mapping and Guiding Regulatory Intervention.” (APSA paper 2021) Under review, Policy Studies Review

Since the Cambridge Analytica scandal, governments are increasingly concerned about the way in which citizens’ personal data are collected, processed and used during election campaigns To develop the appropriate tools for monitoring and controlling this new mode of ‘data-driven campaigning’ (DDC) regulators require a clear understanding of the practices involved. This paper provides a first step toward that goal by proposing a new organizational and process-centered definition of DDC from which we derive a formative empirical index. The index is applied to the policy environment of a leading government in this domain – the European Union (EU) – to generate a descriptive ‘heat map’ of current regulatory activity toward DDC. Based on the results of this exercise we argue that regulation is likely to intensify on existing practices, and extend to cover current ‘cold spots’. Drawing on models of internet governance, we further speculate that this expansion is likely to occur in one of two ways. A ‘kaleidoscopic’ approach, in which current legislation extends to absorb DDC practices and a more ‘designed’ approach that involves more active intervention by elites, and ultimately the generation of a new regulatory regime.

[Open Research Europe Collection] Gibson, R., Bon, E. and A. Rommele. (2022-2023). The Future of Democracy.

‘The Future of Democracy’ Open Research Europe Collection. Gibson, R., Bon, E. and A. Rommele. (Collection Advisors)

Fears and hopes for the future of democracy in Europe and globally are rising. Electorates are seen as increasingly distrustful, divided and disinformed about politics, while pressure for change intensifies from the ‘bottom up’, as younger Gen Z’rs and activist movements campaign for a radical restructuring of established institutions and greater social justice. Underlying and propelling these new trends are rapid technological change, economic crises, a global health pandemic, and a new questioning of established long held norms and orthodoxies such as whether democracies require the losers consent.

This collection seeks to draw together the latest empirical, conceptual and normative research on democracy and political change to spotlight the current strengths and weaknesses of our core democratic institutions, organizations and participatory practices. How durable and robust are they? Are we on the precipice of a new democratic crisis and a move toward more authoritarian modes of rule? Or is democracy simply ‘shape shifting’ into a new, digitally enhanced form with new ideological fault lines and alternative forms of representation?

Supporting the dissemination of all Horizon funded research outputs on democracy as openly, transparently and quickly as possible, this collection accepts a range of article types offered by Open Research Europe – research articles, reviews, case studies, data notes, method articles, essays, software tools, and more.

Potential topics include but are not limited to:

- Models of Democracy

- Political Trust

- The Growth of Populist politics

- ‘Infowars’ Democratic Security and Subversion

- Political Extremism and Polarisation

- Party change and party democracy

- Protest movements and social activism

- The Impact of Global Pandemic on democratic societies

- Media Fragmentation

- Social Media and the rise of platform politics

- Electoral System Integrity

- Inequality and democracy

https://open-research-europe.ec.europa.eu/collections/democracy/about

[Special Issue] (Exp. 2024) Data-Driven Campaigning in a Comparative Context: Toward a 4th Era of Political Communication?

‘Data-Driven Campaigning in a Comparative Context: Toward a 4th Era of Political Communication?’ Media and Communication Special Issue Volume 12, Issue 4. (Accepted, Forthcoming 2024) (Eds) Dommett, K., Gibson, R., Kruikemeier, S., Lecheler, S. and E. Bon

The 2012 US Presidential campaign of Barack Obama was seen as a launch point for a new model of electioneering, one that was driven by scientific modelling, big data, and computational analytics. Since then reports of the spread and power of data-driven campaigning (DDC) have escalated, with the victory of Donald Trump and the Brexit vote commonly attributed to the use of these new techniques. Contrasting accounts, however, have emerged that challenge this narrative in several key ways. Notably, questions have been raised about what is the extent of adopting DDC among political parties, particularly outside of the US? How new is it in historical terms? And how effective is it in actually reaching the target audience and delivering the behavioural change required?

This thematic issue will set out and investigate the key debates surrounding the growth of DDC in comparative and historical perspectives. Specifically, we will highlight a series of core questions that the current literature has both raised and is seeking to resolve. Namely:

- How widespread is DDC adoption across national party systems, and relatedly, does it look the same across different contexts? Is there a one size fits all version or is it adapted to local conditions, and if so, in what way?

- How disruptive is DDC to modern campaigning? Does it represent a new fourth era of “scientific” and/or “subversive” approaches to voter mobilization? Or is it a more “modernizing” force that simply intensifies ongoing trends of professionalization?

- Does DDC actually work? How far are the claims for precision in targeting and attitudinal and behavioural change supported by the evidence “on the ground”?

- What is to be done? To what extent does DDC warrant scrutiny from governments and closer regulation?

We invite original submissions from authors that address these questions from theoretical and empirical perspectives and from differing disciplinary backgrounds. In addition to political scientists, we encourage scholars from related disciplinary fields such as psychology, law, business and marketing, and data science to contribute. Methodologically, we welcome both qualitative and quantitative approaches to the topic. We are particularly interested to receive papers that advance new methodological approaches to address these questions e.g., studies linking survey and other forms of observational digital and trace data, social media network analysis, and machine learning techniques for visual analysis.

Conference and workshop papers

Bon E. (2021) ‘Comparing the value of Twitter and Survey data as a measure of issue salience and most important issue (MII) in an election.

Bon, E. ‘Comparing the value of Twitter and Survey data as a measure of issue salience and most important issue (MII) in an election. Paper presented at the Elections Public Opinion and Parties annual conference, 2021.

Debates about the value of social media versus survey data for measuring public opinion have intensified as usage of the former has spread and increasing problems with the latter have surfaced. Our purpose here is not to ‘re-hash’ these broader debates. Instead we argue that analysis of the merits of social media against survey data should move toward a more purposive ‘horses for courses’ strategy that focuses on the relative value of each source for measuring particular aspects of public opinion. We compare the results from analysis of Twitter API data and online survey responses as measures of issue salience during the 2020 US presidential election campaign. We find that the two sources provide similar if not inter-changeable conclusions about which issues were most salient for voters, but lead to different conclusions about the decisiveness of these issues. Whilst the Twitter sample suggests that the election revolved around COVID-19, the survey data suggests other issues rivalled its impact: the economy, health care and law and order. While we do not definitively rule in favour of one source over the other, on balance we argue that Twitter data may have provided a more accurate reading of issue impact on vote choice.

Gibson, R., Bon, E and A. Rommele. (2021) "Measuring Campaign Change at the Party-level: Designing a New Index for Cross-National Research"

Gibson, R., Bon, E and A. Rommele. “Measuring Campaign Change at the Party-level: Designing a New Index for Cross-National Research” Paper Presented at the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) General Conference, 2021.

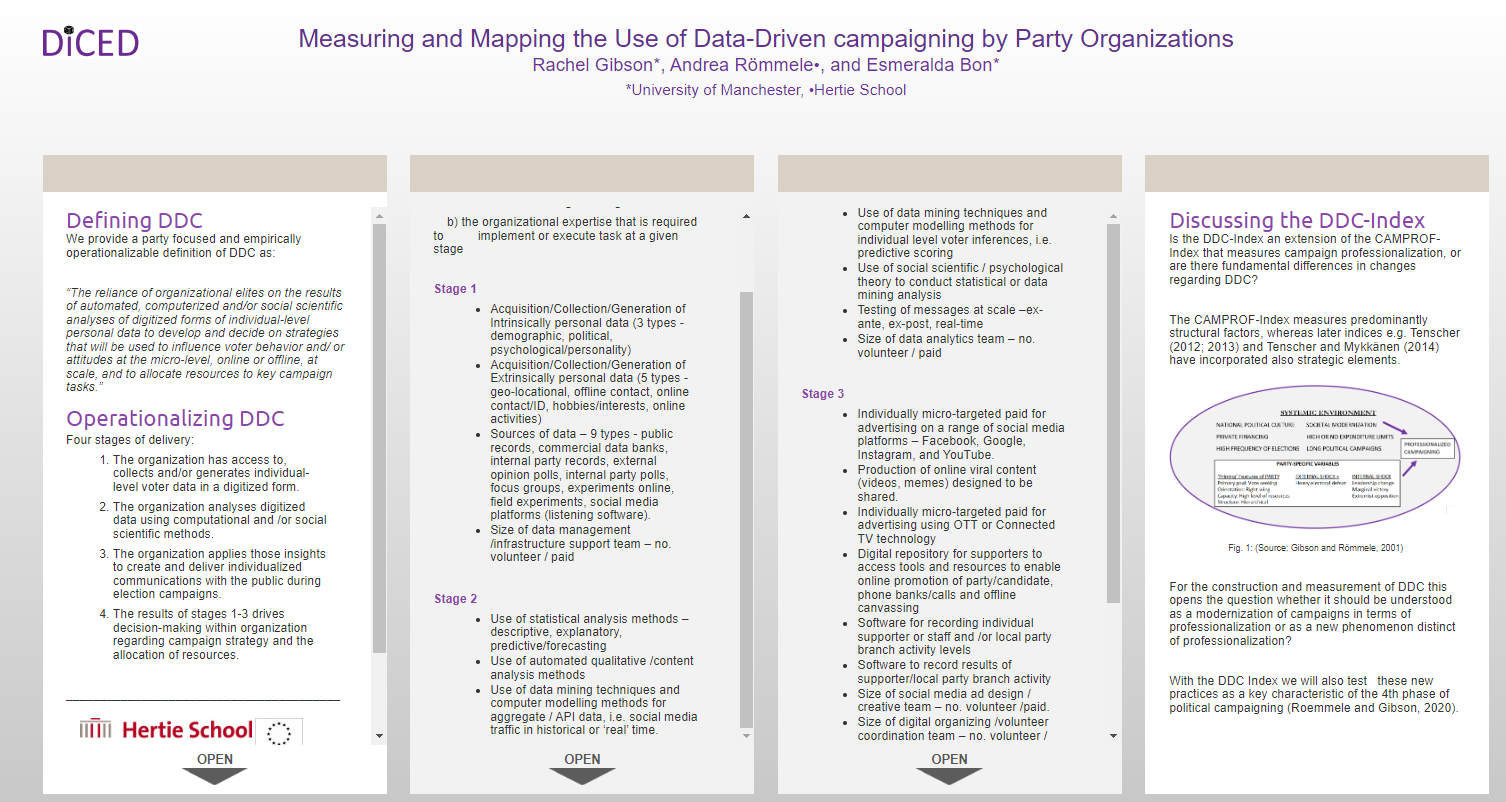

This paper develops a new empirical definition and measure of an emergent mode of electioneering – data-driven campaigning (DDC) – that can be applied to an individual party organizations within and across countries. To do so we first review the growing body of literature on DDC to identify its core components and propose a new organizationally-based definition of the practice, that is more amenable to empirical analysis. We break the definition down into four key stages and assign a range of practical or observable activities, structures and resources to each stage. These operational characteristics are then converted into a set of more quantitatively derived indicators which, when cumulated, provide an indicator of the extent to which DDC is practiced by political parties. The index thus forms the first step toward more systematic analyses of DDC, and particularly the factors driving its adoption as well as its impact on voter turnout and parties’ electoral support. In the second section of the paper we reflect on the relationship of the DDC index to its predecessor CAMPROF, which was designed to measure the professionalization of political campaigns. To what extent does the DDC index constitute a ‘stand-alone’ measure that captures a new and largely independent trend in campaign development? Or, is it better understood in a more integrated manner, i.e. as an extension of CAMPROF, and thus as inevitable next stage in campaigns’ ongoing professionalization?

Gibson, R., Bon, E and A. Rommele. (2021) “Measuring and Mapping the Use of Data-driven Campaigning by Party Organizations”

Gibson, R., Bon, E., J. Nagler and Smyth, P. (2021) “More Demobilized, Distrustful and Disinformed?: Unpacking the effects of social media use on voter behaviour and attitudes in the 2020 U.S. Presidential election.

Gibson, R., Bon, E., J. Nagler and Smyth, P. “More Demobilized, Distrustful and Disinformed?: Unpacking the effects of social media use on voter behaviour and attitudes in the 2020 U.S. Presidential election.” Paper presented at the Annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, 2021.

Social media platforms and websites are assuming an ever more prominent role in election campaigns as official and unofficial political actors flood the internet with online ads, mobilizing hashtags and misinformation, and voters’ increasingly consume, share and comment on this content. The impact of this more immediate and immersive style of campaign communication on citizens’ political behaviour and attitudes and has increasingly preoccupied scholarship over the past two decades. Two of the perennial ‘effects’ questions posed in relation to elections have centred on mobilization and persuasion. To what extent does the internet use actually increase an individuals’ likelihood to turnout, and can it convert or persuade an individuals’ to support a particular party or candidate (REFS)? A third and more recent question to emerge in the era of growing global support for populist parties’ and candidates, is the extent to which greater use of social media may help to foster mistrust in mainstream politicians and the political process itself, and even potentially decrease citizens knowledge of current affairs (REFS). Accurate investigation of these questions has proven difficult due to the lack of precise measures of what voters are exposed to online in advance of an election and the ability to link this with changes in their vote decisions and attitudes toward parties and the broader political system. This paper meets this challenge by exploiting the results from a bespoke social media analysis (SoMA) panel that conducted with YouGov during the U.S. 2020 Presidential election. The panel tracks over 1,500 respondents’ Twitter use and web browsing habits during the campaign and combines this with survey data measuring change in several key political indicators such as vote intention, trust in the political process, institutions and individual candidates, as well as accuracy in understanding the current economic and health situation facing the U.S. Through this powerful research design we are able to identify the extent to which exposure to, and interaction with, social media and web content affected individual voter decisions, their views of the candidates and the issues that mattered in the election, as well as trust in the electoral process and knowledge of current affairs? We are also able to probe which sources were most influential in generating these effects. How widely consumed was the content of the official campaigns and mainstream media versus that produced by unofficial actors? Investigation of these questions is important given the growing concerns about the disruptive, divisive and demobilizing impact of social media within democratic elections worldwide. It is particularly timely in the context of the 2020 U.S. Presidential election, given the COVID-19 crisis resulted in the shift of most campaign activity from the offline to the online sphere. Engagement with the digital election was likely to be running higher than at any previous election globally, increasing both the opportunities for and pressure on researchers to understand wheher and how this changing context if affecting democratic engagement.

Dommett, K. and R. Gibson (2022) “How New is Data Driven Campaigning?”

Dommett, K. and R. Gibson “How New is Data Driven Campaigning?” Paper presented at Norface project meeting June 2022. Under revision for Media and Communication Special issue ‘Data Driven Campaigning in Comparative Perspective’

This paper is divided into three main sections. First we examine the claims for DDC as a ‘new’ form of campaigning and set out the implicit and at times explicit arguments made in the literature in favour or against its originality. Second, we set out the empirical case for and against accepting these arguments and in a final step we articulate why it matters which version of DDC is accepted. Broadly speaking, we can divide the literature dealing directly or indirectly with DDC into three main perspectives in terms of the extent of change that is seen as occurring or anticipated as result of its adoption. The first is a ‘null’ or no change perspective in which DDC is either seen as not in fact being particularly new and different to former practice and / or not being widely implemented across most parties and party systems. A second body of work accepts significant changes are occurring but interprets this in terms of a shift in means and mode, which is bringing about substantial increases in the efficiency and sophistication of campaigns, but leaving their core goals, activities the same. DDC according to these scholars is simply reinforcing and intensifying ongoing trends of organizational professionalization. A third viewpoint offers a much more disruptive understanding of DDC and envisages it to present a radical change in campaigns’ modus operandi and their wider role within the democratic system. Specifically this takes one of two forms. The scientific version argues that DDC is bringing a wholly new methodology to campaigns’ operation, which is effectively changing them from an ‘art’ to something much more of a science. Where once key decisions about allocating resources for canvassing and message construction were made by those with extensive field experience who may have made use of polling and focus group data, but relied primarily on their intuitive knowledge of the electorate’s mood, the role of human intelligence is now displaced by AI and algorithmic decision-making. The ‘nerds’ have now gone marching in (Gibson, 2020), ‘everything is measured’ tested, and adjusted based on data mining techniques. The second variant to the disruption thesis is that of ‘subversion’. The claim here is that DDC signals a profound change in the outcomes and goals of campaigning rather than process. In this scenario, campaigns are now increasingly engaged in activities that are designed to, or inadvertently subvert the democratic process. Data-driven techniques and particularly the use of digital micro-targeting open the way for voter manipulation, unaccountable advertising practices that rely on emotive and psychographic profiling, privacy violations, political redlining (exclusion of certain voters from the polls) and even the deliberate suppression of opponents’ supporters’ incentives to vote. Where once campaigns may have strayed into negative advertising and used such appeals as a ‘shock’ tactic, the term itself reflecting the infrequency of such tactics, in the era of DDC, such questionable methods are increasingly more pervasive and less detectable as they become naturalized into the DNA of electioneering.

Dommett, K. R. Gibson, E. Bon, S. Kruikemeier, and S. Lecheler. (2022) “Is banning political microtargeting the right approach? Assessing the Public Acceptability of Political Microtargeting Data Inputs”

Dommett, K. R. Gibson, E. Bon, S. Kruikemeier, and S. Lecheler. “Is banning political microtargeting the right approach? Assessing the Public Acceptability of Political Microtargeting Data Inputs” Paper presented at the ECPR General Conference 2022

To date, coverage of online political microtargeting has tended to focus on its negative consequences for democracy and has sparked numerous calls for platforms and policymakers to limit or ban this activity. Whilst an important mechanism for curtailing problematic practices, this response conveys the impression that the use of personal data for microtargeting is uniformly bad. Within this paper we explore this idea. Gathering new data on public perceptions of data use in three countries – the US, Germany and Netherlands – , we consider whether concerns about data are uniform. Uncovering important variations in not only what data is acceptable, but by whom, we build on a small body of work about the positive potential of microtargeting, and call for a more nuanced debate about the use of data in politics.

Dommett, K. R. Gibson, E. Bon, S. Kruikemeier and S. Lecheler. (2022) “Shifting the Focus: Assessing the Public Acceptability of Political Microtargeting Data Inputs”

Dommett, K. R. Gibson, E. Bon, S. Kruikemeier and S. Lecheler. “Shifting the Focus: Assessing the Public Acceptability of Political Microtargeting Data Inputs” Paper presented at ECPR 2022 Annual General Conference (Joint with Norface)

To date, coverage of online political microtargeting has tended to focus on its negative consequences for democracy and has sparked numerous calls for platforms and policymakers to limit or ban this activity. Whilst an important mechanism for curtailing problematic practices, this response conveys the impression that the use of personal data for microtargeting is uniformly bad. Within this paper we explore this idea. Gathering new data on public perceptions of data use in three countries, we consider whether concerns about data are uniform. Uncovering important variations in not only what data is acceptable, but by whom, we build on a small body of work about the positive potential of microtargeting, and call for a more nuanced debate about the use of data in politics.

Gibson, R. Tsenina, A. and E. Barrett. (2022) ‘Online Political Micro-targeting: An Unclear but Present Danger to Democracy?’

Gibson, R. Tsenina, A. and E. Barrett. ‘Online Political Micro-targeting: An Unclear but Present Danger to Democracy?’ Paper presented at the Digital Campaigning in Dissonant Public Spheres, International Conference May 8-11, 2022.

A review article on the negative impact of Online Political Microtargeting. In recent years, scholarly attention has shifted from the study of digital technology as a democratising force to analysis of its potential to disrupt and harm democratic systems. Much of this new interest has centred on how digital technology fuels electoral interference and political manipulation by promoting the spread of false information designed to confuse, enrage or mislead voters. Less attention has been given to a range of less obvious, but arguably equally pernicious threats stemming from more ‘conventional’ uses of digital technology by political campaigns. This paper focuses on the potential harms to democracy associated with the growing use of digital political micro-targeting (DpMT) in elections. Drawing on contemporary democratic theory we unpack the process of DpMT to identify four normative conditions for a well-functioning polity that it puts at risk: (1) the capacity of citizens to make informed choices; (2) inclusivity of participation; (3) the level of perceived and actual representation; and (4) procedural legitimacy and trust in outcomes. We review recent empirical studies of DpMT to see whether the evidence is indicative of any erosion in these normative conditions. Our findings raise questions about whether DpMT is a democratically-sustainable form of political campaigning. In particular we identify concerns for the longer term health of democracy caused by the rapid adoption of these tactics for short-term electoral gains. We conclude with a call for researchers to adopt a more explicitly normative ‘means-ends’ framework in the design and construction of future studies of this increasingly widespread phenomenon, with attention being given to exploring how DMT might be better deployed to support and sustain democratic goods.

Gibson, R., Bon, E and A. Rommele. (2022) “Data Driven Campaigning in the 2021 German Federal Election: An inter and intra-party analysis”

Gibson, R., Bon, E and A. Rommele. “Data Driven Campaigning in the 2021 German Federal Election: An inter and intra-party analysis” Paper presented at APSA 2022 Annual General Conference

This paper will examine the adoption of new Data Driven campaign (DDC) techniques within the German party system, and how this is affecting inter- and intra-party power relationships. While DDC is still in an early stage of development in many countries (outside of the U.S.), several key features have been defined in recent academic literature. These features include the automated collection, analysis, and application of new forms of digital data to send voters more personalised or micro-targeted messages. To date, much of the attention has focused on the external uses of DDC and particularly changes in campaign advertising transparency and the impact on voters. However, DDC is also likely to have a significant impact on parties themselves in terms of their levels of competitiveness within the party system, and their internal distribution of power. Specifically DDC is likely to reinforce the advantage of bigger well-resourced parties who can build up their data reserves and technical expertise in targeting voters. It is also likely to affect intra-party organizational structures in terms increasing specialisation of digital campaign expertise, and the centralization and automation of decision-making. In this paper, we examine these contentions with a case study of the German party system during the most recent Federal election. We start by contextualising the German case in the comparative literature and identifying a range of factors that constrain the use of DDC by parties. We then explore rates of adoption of DDC by a range of major and minor parties using original data collected in a post-election survey of parties’ digital campaign staff. We use these data to assess the extent to which DDC is affecting inter-party competition and the role of intra-party structures and operations in determining its uptake. Our conclusions show that DDC is still relatively under-developed in Germany, that the larger parties are more generally more advanced. However, the internal factors driving adoption need further exploration via more qualitative research.

Work-in-progress (e.g., working papers)

Comparative Positives paper 2 Joint Norface empirical paper on positives of PMT

This paper would take the findings from the joint Norface ECPR paper 2.ii) and examine the question of positive effects with empirical data that would test the impact of receiving DDC on voters’ political participation, including vote and other activities. Preliminary investigation of the Dutch data has shown a positive impact of parties’ email and social media contact on individuals likelihood to participate, this is stronger than for other types of campaign stimuli. We would extend to Germany and the U.S.

Comparative Perceptions paper 2 Joint Norface

This would build on paper 1 point six, which is to examine the linkage between the different dimensions of perceptions of DDC. Currently we have identified at least 4 in our data: Awareness, Acceptance/Concern, Affect (like/dislike) and Knowledge. We would be interested next to explore how these dimensions relate to each other by way of SEM. This could involve hypothesizing the inter-relationships between them, i.e. does higher awareness link with higher knowledge, and in turn does this increase concern and dislike. Or do people that know more feel more relaxed and accepting? We could build a possible typology (developing that of Sophie Minihold) that would potentially examine the impact of the varying configurations, i.e. high concern, low knowledge on other attitudinal and behavioural variables of interest. E.g. trust, satisfaction with democracy, online and offline engagement.

Horses for Courses paper 2

This would build on paper 1, aspect five, by presenting present an extension of U.S. analysis to German and French twitter data to generate a comparative methodological paper. Do same findings hold cross nationally when comparing MII on survey and social media data. Option to use the Social media panel and compare their survey responses WITH against their twitter data to do a direct comparison

Demobilized paper 2

This would involve an extension of U.S. analysis to German SoMA panel data to test negative impact of left and right wing DDC campaign content exposure on voters.

Collaborative project with SPARTA

Idea would be to analyse the aggregate German twitter data to extend the influential Barbera et al. paper on ‘Who leads Who follows?’ Goal here is to run an over- time analysis during the German election campaign about who led the agenda on Twitter. Our innovation would be to examine a new context and also introduce the mainstream media as an actor to add to the two-actor focus of the Barbera study examining elites /politicians, or the people.

New paper examining Digital activists/affiliates on Twitter and their roles communication during the campaign

Idea here is to examine the emergence and impact of a new set of political actors facilitated by digital campaigning rather than DDC specifically. We have identified a new type of political campaigner – political ‘influencers’ i.e. quasi-official individuals that play a role in mediating campaigns messages. These are typically individuals but could be organizations i.e. Momentum in the UK? The idea would be to set up a classificatory schema to first conceptualise and define these actors and fit them to a continuum or categorisation scheme, with a view to drawing out greater or lesser influence, and higher or lower proximity to power, and wider or lesser reach. Having identified them it would be interesting first to compare across countries how prominent they are in the national election debate i.e. across U.S. Germany and France. Then we could potentially seek to examine their influence on voter choices through our SoMA panel.

Paper about our findings from German focus groups, perceptions of political advertising

We will collect qualitative data from our FG that will allow us to explore in more depth in each of our 5 countries citizens feelings about the targeting of online political adverts, particularly on FB. We will gather some limited metrics through pre and post surveys and online tests during the FG. We will prompt with a range of mobilizing vs persuasion adverts, and explore what people understand about the level of targeting that currently occurs in their country, and what they do and don’t find acceptable and why. We will trial different options for increasing transparency in ads in terms of the type of targeting information provided, and how it is presented.