The impacts of an ageing future

by Jennifer Collins

As the baby boomers retire and more people live well into their 80s, making the ‘oldest old’ one of the fastest growing demographic categories according to Timonen (2008), questions have to be asked about what rights are in place for the elderly. How can public space be adapted to accommodate the elderly? Can social isolation be prevented? And who will support the Millenials financially? These questions highlight the political, environmental, social and economic considerations of ageing. Improvements to public health, nutrients and medical advancements leading to increasing life expectancies, particularly in MEDCS, are putting these questions at the front of sociologist’s minds.

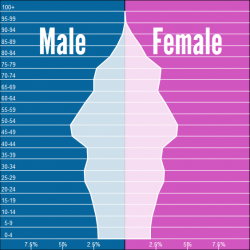

Fig. 1: Ageing societies, Germany

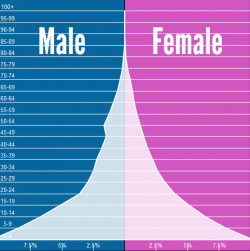

Arguably demographic changes are highly influential factors contributing to an increase in ageing populations, with death rates falling due to the factors mentioned above and birth rates also falling due to factors like better sex education, accessible family planning, more widely available contraception and lower infant mortality rates, which is particularly influential in LEDCs where lower infant mortality rates mean families have less children as there is more chance that each child will survive. This demographic change can be visualised by comparing population pyramids, the two pyramids to the left and below are contrasting Germany and Niger. While Germany’s shows a narrow base and therefore a low birth rate and ageing population, Niger’s has a large base and therefore a young population, with only 0.6% of the population reaching the age of 65-69 in 2015.

Fig. 2: Ageing societies – Niger

In her blog post ‘Predicting the Future and Getting a Job’, Sternheimer highlights that an ageing population will have major influences on the job market which can impact a country’s economic standing and job types. Not only will an ageing population change how long people work and the levels of competition, Sternheimer also infers that the requirements of caring for an ageing population will change the types of job positions that need to be filled. There will be less demand for childcare as birth rates drop and increased demand instead for healthcare services and retirement care providers. These ideas are supported by reference to statistics from the US Bureau of Labor who suggest a ‘28.6%’ growth in ‘audiology and health professionals that test and treat hearing loss’ as hearing loss occurs due to ageing- whether these changes to the market are seen as positive or negative impacts is arguable.

It is a common idea that the elderlies’ impact on society’s structure has seen the formation of a new market; known as the ‘grey pound’. Lumbers’ (2008) research expands on this and suggests they use their market impact for their own purposes, for example, using consumerism as a leisure activity or a way to socialise, which Lumbers (2008) sums up with her interview quotation:

“It’s nice to go wandering round just to see what different things there are…and it keeps you alive, you know, you see what’s going on and you meet different people (Bristol, 55-65, female)” (pg. 296) /em>

This could be interpreted as the elderly using their impact on society to tackle social challenges that an ageing population can bring, like social isolation and social integration.

The attitude that the elderly are valuable members of society is popular across Asian countries such as China and Japan, which are facing similar demographics to western countries. Whilst some argue that working elderly will cause complications around training and workplace structures, it appears that Japan’s ‘solution’ to having one of the largest ageing populations was to raise retirement age which saw a drop in unemployment rates, as explained in the Independent’s news article ‘Japan’s elderly keep working well past retirement age’. However, it can be debated whether living standards and ageing population’s social challenges are worsened by this approach.

It is interesting to consider whether ageing populations will challenge the timeline of traditional life events, such as further education being carried out more commonly in later life rather than in late teen years- as seen already in China.

As more countries face ageing populations, the impacts of a country’s population structure changing are in a way timeless as society has to adapt in different ways as populations age – for example, the post WW2 birth rate increase has seen ‘baby boomers’ add strains to education systems and now potentially multiple aspects of society will struggle as they retire. Therefore, it is important to study demographic patterns, especially within sociology and social policy, as when the structure of a country’s population alters the changes are felt throughout society.

Photo by Chalmers Butterfield

References

Timonen,V. (2008). Ageing societies: a comparative introduction. Open Univ. Press

Lumbers, H. (2008). Understanding older shoppers: a phenomenological investigation, Journal of Consumer Marketing. Vol. 25 Iss 5, pp. 294 – 301

0 Comments