Inequality in the UK higher education system

(illustration by Ellen Winkler and Robert McGrath, published in The Chronicle of Higher Education)

post by Jack Brown

Despite only 6% of young people being educated privately in the UK, they make up 55% of students at Russel Group universities. This is a problem that perpetuates the entrenched foundations of inequality by limiting the scope for social mobility within Britain’s most disadvantaged communities. Coverage has recently quietened on the state of inequality within the university application system, as applications from disadvantaged students are at an all-time high. However, this does not mean that there is no longer a cause for concern. The rate of acceptance from wealthy communities is rising at a faster rate than from disadvantaged communities, therefore accelerating inequality in higher education. The progress made in getting disadvantaged students into university has largely only had an impact in less established universities, with high tariff institutions being further behind the pack in diversifying their applicants. This is an issue accentuated by the fact that high tariff institutions are actually growing in their proportion of total UK applications. This is clearly limiting the opportunities for disadvantaged students in higher education further; degrees from high tariff institutions are often held in higher regard by employers, and provide more social mobility from a sociological perspective. This is not a problem exclusive to traditional university degrees. Degree level apprenticeship places, traditionally perceived as a more accessible route for the working class, are also over half filled with students from the UK’s most advantaged social backgrounds.

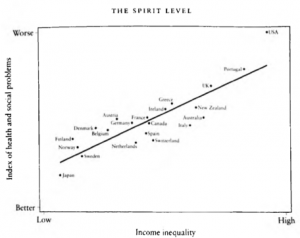

Wilkinson, R. G. & Pickett, K. (2010). The spirit level: why equality is better for everyone. London: Penguin. p. 20.

The impact of this inequality on society is undoubtedly profound, especially when considering the sociological aspect presented by Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson. Pickett and Wilkinson suggest that more unequal societies facilitate a greater level of health and social problems. Therefore, inequality in British higher education comes at the detriment of societal wellbeing due to its reinforcement of pre-existing social and economic inequalities. The social problems identified by Pickett and Wilkinson include social mobility as well as children’s educational performance; these are problems that can be improved through access to higher education. Inequality in university applications can, therefore, be seen as a cause and a consequence of social inequality, a sociological understanding of the impact of educational inequality would, therefore, be a step in the right direction in tackling this problem institutionally. Inequality has a geographic dimension too; eight times as many applicants from Richmond, London were accepted into the University of Cambridge between 2010-2015 as those from Blackpool, Hartlepool, Middlesbrough, Salford, and Stoke combined. This geographical inequality further emphasises the importance of combating the inequality of higher education in a wider context. Greater access to high tariff universities for students in the north could help to tackle the regional inequality of the ‘north-south divide’.

This level of inequality cannot be explained by educational attainment alone, which critics might suggest as a valid explanation for the discrepancies in Russel Group applications in particular. In fact, A level grades are actually increasing in disadvantaged communities, while slightly regressing in the most advantaged. Furthermore, even when both wealthy and disadvantaged state school students come out with equal A-levels, the wealthiest students are still admitted 5% more often. Labour MP David Lammy suggests that high achievers in disadvantaged communities are in fact more deserving of a top university place as they have likely overcome more social barriers than their well off counterparts. A number of other reasons could be attributed to the level of inequality in higher education. Although the Education Secretary Damian Hinds has insisted that there is no evidence that tuition fees act as a deterrent, Oxford Professor Danny Dorling argues that many disadvantaged families do not understand the workings of the student loan repayment scheme. This creates a psychological as well as an economic barrier to applying to university. Many prospective applicants may have also looked to the experiences of their working-class peers in higher education as a turn-off, as disadvantaged students are more likely to drop out according to the Telegraph.

This is a problem a long way from being resolved, however some institutions represent bright spots in the fight against educational equality. For example, Cambridge have recently pledged to offer disadvantaged students a second chance to apply if they fail to secure a place on results day, whilst the London School of Economics are using a data-led approach to ensure disadvantaged students get fair representation in the application system.

0 Comments