From supporting to deporting – Britain’s changing attitude to migration?

Article by Honor Pullman

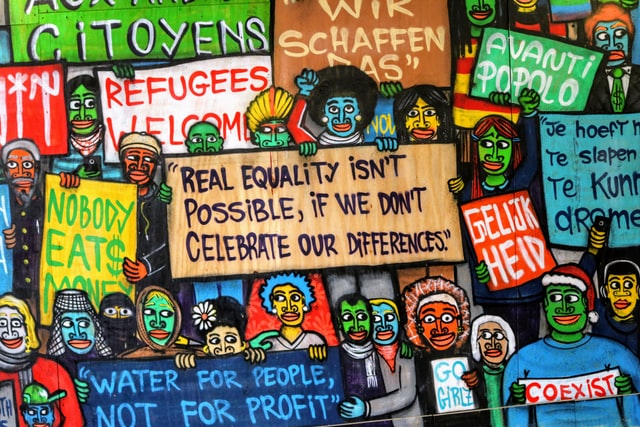

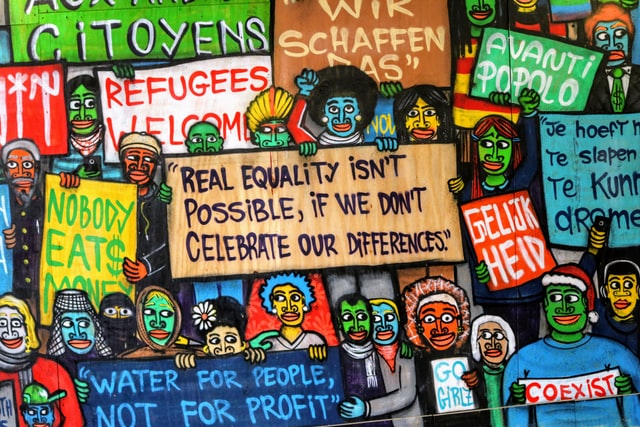

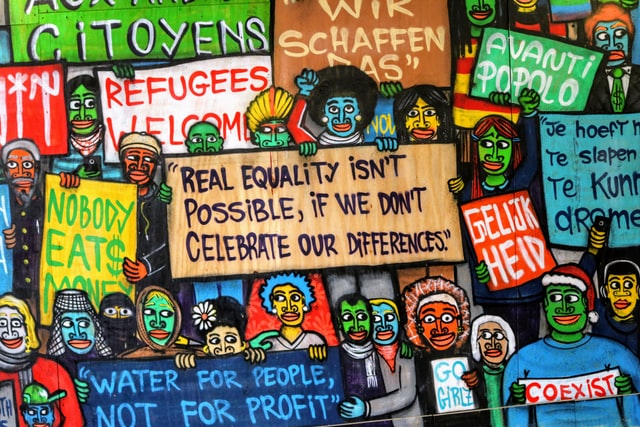

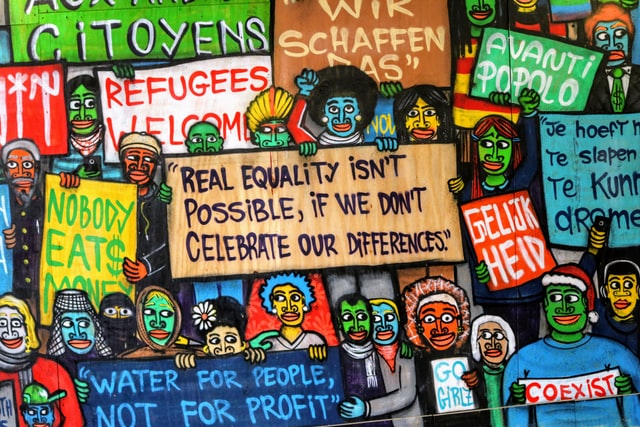

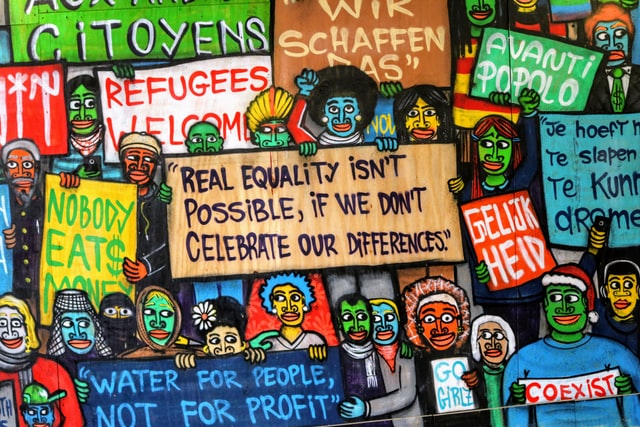

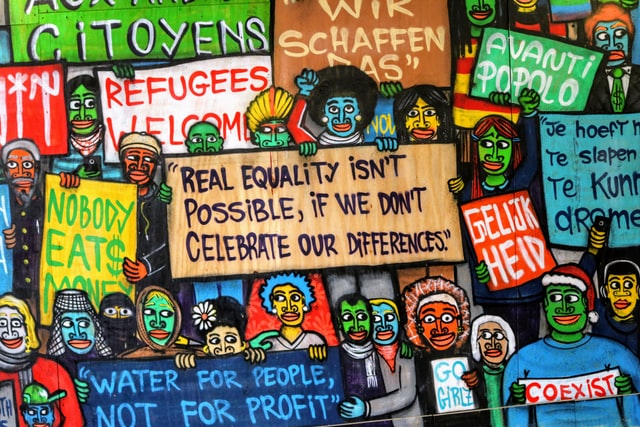

Photo by Matteo Paganelli on Unsplash

Imagine you’ve spent your entire life in one country – for many of you, this will be the case. You’ve built the foundations of your relationships, job, and family there, and you consider it your home. Now imagine that you’re arrested, labelled as ‘illegal’ and sent off to a country you’ve never been to in your life. This was the reality for hundreds of second-generation immigrants during the ‘Windrush Scandal’ of 2018. The wrongful deportation of 83 British citizens is just one example of Britain’s ever-growing hostility towards migrants.

Immigration remained a relatively inconsequential issue up until the late 1990s and early 2000s – for example in, January of 1999, approximately 5% of the public voiced immigration as one of the most important issues facing the British public. By January 2013 this had risen to roughly 35% (Immigration as an important issue by UK net migration, 1974 – 2013, Office for National Statistics). This is a microcosm of the rising hostility towards migration to Britain, driven by stringent laws and harsh discourse.

The highly publicised ‘Nationality and Borders Bill’ received widespread media attention and scrutiny for its arguably draconian measures – the bill would allow for the removal of individuals’ citizenship without warning and would give the government the power to turn back or criminalise people attempting to cross the channel. The pandemic and the humanitarian crisis in Ukraine have allowed the bill to sneak through the House of Commons without much opposition, and it is currently in its final stage in the House of Lords. The government’s antipathy towards migration hasn’t stopped there, however, in recent weeks Britain has come under intense criticism for its delayed response to the Ukraine refugee crisis.

Nearly two weeks after the outbreak of war in Ukraine, Britain had granted only 1,000 visas and only to those with family in Britain. This contrasts starkly to EU countries that have welcomed over 304,000 collectively, and neighbouring states such as Poland taking in at least 1.4 million. (Operational Data Portal – Ukraine Refugee Situation, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) So, why is Britain so unwilling to accept migrants? Well, it wasn’t always like this.

There was a time when Britain welcomed immigrants and refugees with open arms, and a precursor to the ‘Windrush Scandal’ was Windrush itself. Post-war Britain needed help to rebuild its economy, and in doing so placed advertisements in Jamaican newspapers in 1948 to encourage migration. Approximately 400 people from the Caribbean travelled to Britain on HMT Windrush Empire, and this was just the beginning – it’s estimated that from 1955 to 1962 Britain’s net intake from the commonwealth was roughly 472,000 (ONS, Level of Annual Net Migration to the UK). This pro-migration attitude conveyed by the government started to shift as the numbers rose – from 2003 to 2004 net migration had risen to 268,000 and with this came new anti-immigration rhetoric being pushed by Her Majesty’s Opposition. The 2010 general election marked a turning point in Britain’s discourse around migration and shaped it into the rigorous policies we see today.

In the run-up to the election, David Cameron stated that if he won, he would reduce net immigration down to tens of thousands per year – an ambitious target that many deemed unachievable, including expert organisations such as Oxford University’s ‘Migration Observatory’. As expected, Cameron did not deliver on this promise, and he was forced to introduce harsh immigration policies to make up for it – these included the notorious ‘hostile environment policy, which aimed to make Britain an inhospitable environment for illegal migrants. This anti-immigration rhetoric came to a head in the 2016 Brexit Referendum, whereby the ‘Leave’ campaign capitalised on the public’s fear surrounding job insecurity and housing to push the agenda that had been forming over the last 6 years. And they succeeded – which brings us to 2022.

We find ourselves in the midst of another humanitarian crisis gripping Europe. While I sit here writing this, Britain is still dragging its feet on accepting Ukrainian refugees. The images of families fleeing with all their belongings in mere plastic bags are burned into my brain; meanwhile, the government asks them to pay to apply for visas, submit biometric data and more. It’s a far cry from the government that sent out invitations to the West Indies, encouraging them to migrate, and reinforces the ultimate question – how did we get here?

From supporting to deporting – Britain’s changing attitude to migration?

0 Comments

Submit a Comment

From supporting to deporting – Britain’s changing attitude to migration?

0 Comments

Submit a Comment

From supporting to deporting – Britain’s changing attitude to migration?

0 Comments

Submit a Comment

From supporting to deporting – Britain’s changing attitude to migration?

0 Comments

Submit a Comment

0 Comments