’Local exploitation’ scenario

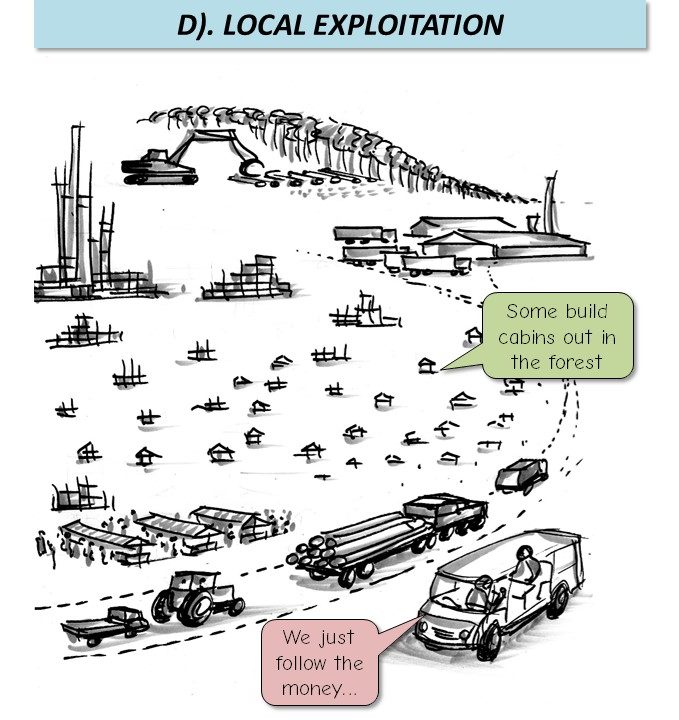

Extract-opolis: – or – ‘This land is our land’

A day in the life…. ”Maria & Sauli were struggling with the climate on their way through the forest. The melting arctic ice and permafrost had brought a ’warm-storm’ from the north, and the air was so thick with mosquitos, seeing and breathing was difficult, even with full body suits. Meanwhile back home, their business was doing ok. In the winter they organized forest hunting trips, using the latest apps, satellite imaging and drone technology. Their urban visitors would use hyper-sensory VR, to experience the deer and moose in microscopic detail, as they raise their young and look for food, before killing them in the most entertaining ways…

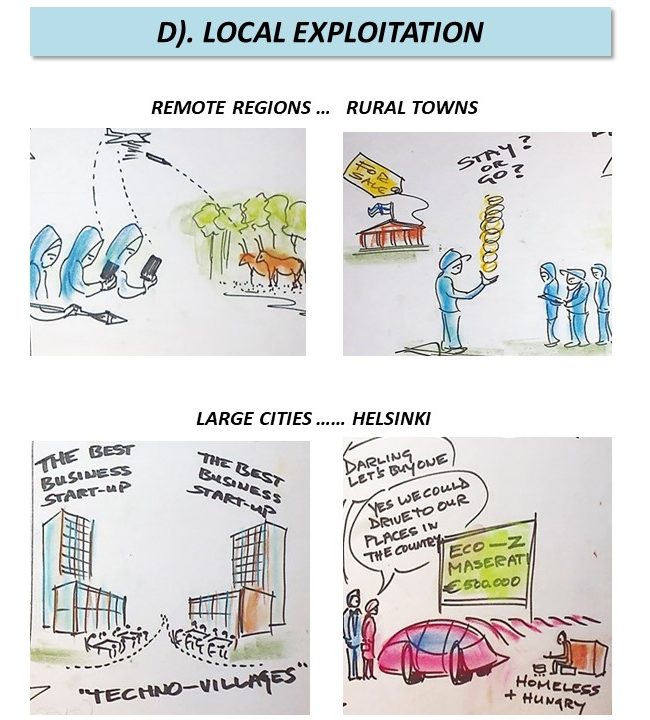

In the summer Maria and Sauli migrated as nomads in their camper van, into the towns and cities, with a bag of travel passes, licenses and permits, for the new ’autonomous’ local areas. In many rural towns and villages there were local entrepreneurs, selling the forest products and bio-economy materials, which (in theory) belonged to ’the community’. If the young people stayed they could work on virtual platforms – if they went to the big cities there were more opportunities, but nowhere to live, as each municipality provided only for local people. If they were really smart they could get into the new markets for eco-technologies and carbon quota auctions – so they planned to buy a Eco-Maserati and make big money, providing high-value eco-travel for urban leisure-seekers.

Storyline

Here the results of ’localism’ are different to the text-book advice of local = sustainable: many local communities seem happy with a free market exploitation of resources. Rural communities produce local entrepreneurs who begin to harvest the forests and bio-economy materials in a big way, sharing the work around their villages and towns. In the urban areas, inner city neighbourhoods and suburban communities bring new localized enterprises, where the profits tend to stay local, and are reinvested in community-based projects and services. While the metropolitan region suffers from a lack of strategy and coordination, each municipality and each neighbourhood seems to build more self-reliance and self-organization. This helps to counter the more extreme effects of climate change, with global tipping points leading to storms, floods, heatwaves and sea level rise, leading to invasions of pests and diseases. This pushes more people into a co-location nomadic kind of existence, between urban or rural, and summer or winter.

Keyparameters

Axes of uncertainty:

- Techno-economic systems: Closed local boundaries, slow innovation

- Socio-political structures: Equal & flexible

- Climate & natural resources: Exploitation, rapid climate change

Spatial dynamic

- Regional development : Rural region growth

- Urban form: Decentralized: growth of isolated communities in villages & forests

Counter dynamics: Urban sustainability movements, resistance to material production focus, aiming to rebuild non-material values and communities and networks.

Wild cards & shocks: Climate change accelerates with major tipping points

Key growth factors: population high growth: GDP medium growth

Regional profiles

- Remote regions: Digital hunter-gatherer communities

- Rural towns: Migration of young people

- Large cities: Technology islands in competition

- Helsinki metropolis: eco-living for the wealthy

Implications for research

This scenario questions on Finnish governance which is assumed to be rational, democratic, public interest. There are parallels in other large and resource-rich countries, where small communities form on an open free market basis. The application of digital tech to hunting and similar could be interesting. The emerging co-location economy might also apply on a regional scale with the ’new nomads’.