Written by Jed Winstanley, Honorary Research Assistant, CARMS Project

Hello again and welcome back to the blog concerning all things CARMS!

The CARMS (Cognitive AppRoaches to coMbatting Suicidality) Project aims to understand the pathways to suicidal thoughts and acts experienced by individuals alongside investigating the efficacy of a new psychological talking therapy designed to reduce suicidality in people who experience or have experienced psychosis and suicidal thoughts or feelings. Considering this I thought it’d be fitting to write up a blog post concerning suicidality. More specifically what suicidality means, why people may experience suicidality, and some potential ways of treating suicidality.

First off, some definitions…

Suicide is defined as ‘the act of taking one’s own life voluntarily and intentionally’ 1 whilst suicidality encompasses suicidal thoughts (or suicidal ideation), suicide plans and suicide attempts. The World Health Organisation estimates around 800,000 people end their life through suicide each year2 so it is safe to say that death by suicide is a serious public health problem. Furthermore, every life lost to suicide is a personal tragedy and the negative consequences can be seen on both an individual and societal level. On an individual level at least six people may be directly affected by a suicide3 and on the societal level suicide can greatly impact health service provision such as within the UK’s National Health Service (NHS). Acute psychiatric healthcare accounts for over two-thirds of NHS costs4 and approximately one-third of deaths by suicide occur in people accessing mental health services5. That’s not to say that mental health problems are the primary cause of suicidality. Suicide behaviours are complex, individualised and many different factors can interact to increase a person’s risk of suicidality.

As a mental health support worker…

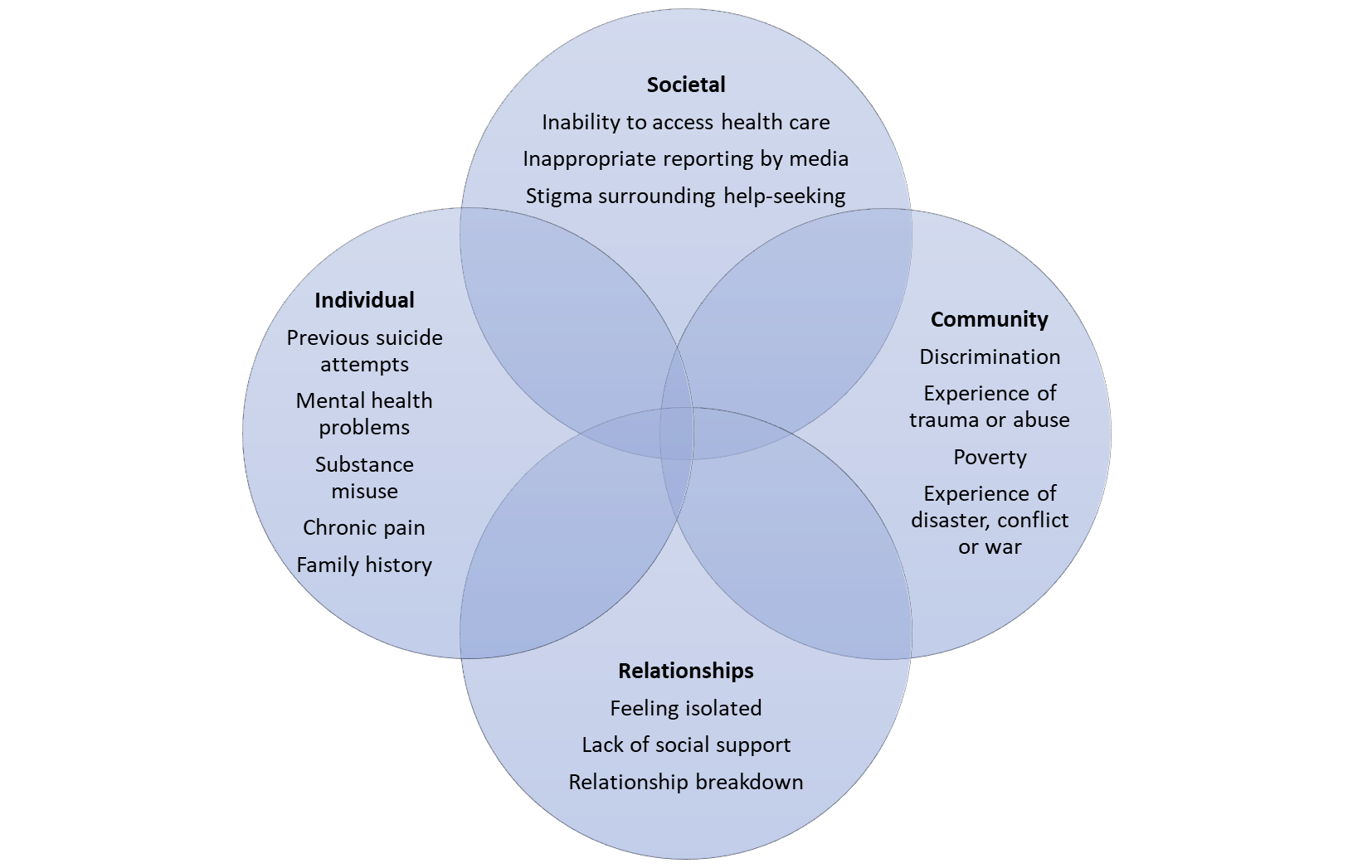

I regularly meet people who experience suicidal ideation and repeatedly attempt to end their life so have often questioned how a person could reach a point in their life where they feel the only option left available to them is suicide. Some risk factors that may lead to suicidality include: difficulties in accessing or receiving health care; experiencing stigma when trying to seek help; experiences of trauma or abuse; relationship breakdown; previous suicide attempts; or a family history of suicide6.

Fig 1. Factors that may increase the likelihood of a person experiencing suicidality6

Cognitive Behavioural Suicide Prevention

Death by suicide is preventable7 so identifying treatments to reduce suicidality in populations at increased risk for suicide is urgent. The evidence base for psychological treatments, such as cognitive-behavioural therapy8, for self-harm and suicidality is growing9,10.However, the CARMS project aims to assess a novel approach known as cognitive-behavioural prevention for suicidality (CBSP) in psychosis.

The CBSP intervention is designed to reduce suicidality in people who experience or have experienced psychosis and suicidal thoughts or feelings. CBSP is based on the Schematic Appraisal Model of Suicide (SAMS), which states that suicidality arises from three core psychological components: an increased tendency to process negative information; having established suicide schema as an escape strategy; and a negative and suicide-focused appraisals system11. Targeting an individual’s information processing biases and appraisal system12 has been shown to directly treat the suicidal, cognitive processes thought to underpin suicidality in people with schizophrenia and prisoners who are suicidal, thus reducing suicidal ideation and suicide probability13,14.

If you would like more information about the CARMS Project please contact Charlotte Huggett by telephone: 0161 2710729.

Thank you for taking the time to read this article and I look forward to seeing you here again next time!

Next time: Looking at myths and facts about suicidal thoughts and behaviour

* This article contains references to suicide that some people may find distressing so if at any point you require urgent support with your mental health please contact your GP, care coordinator or crisis team. Other help can be found here:

- Samaritans

- Phone 116 123

- Email jo@samaritans.org

- Text 07725 90 90 90

- Or visit your local branch

- The Calm Zone

- Papyrus

- Self Help Services

- Online crisis support selfhelpservices.org.uk/the-sanctuary

- Phone 0300 003 7029

- Rethink (Mon-Fri 9.30AM-4PM):

- Phone 0300 5000 927

- Saneline (4.30PM-10.30PM):

- Phone 0300 304 7000

- Mind (9AM-6PM):

- Phone 0161 236 8000 (local rates and mobile charges apply)

- Email info@mind.org.uk

- Text 86463

- The University of Manchester Counselling Service

- Zero Suicide Alliance Free Course: let’s talk about suicide

-

References:

- https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/suicide

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

- Maple, M., et al. Silenced voices: Hearing stories of parents bereaved through the suicide death of a young adult child. Health and Social Care in the Community 2010; 18(3): 241-248.

- Knapp M, McDaid D, Personage M. Mental Health Promotion and Prevention: The Economic Case. Department of Health, 2011.

- National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness (NCISH). Annual Report. University of Manchester, 2017.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. Retrieved from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/131056/9789241564779_eng.pdf;jsessionid=B93BD7CD8DCA08E9CFB3E09933AB0532?sequence=1

- Naghavi M, Global Burden of Disease Self-Harm Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ 2019; 364: l94.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Self-Harm. Longer Term Management. CG133. NICE, 2011.

- Tarrier N, Taylor K, Gooding P. Cognitive-behavioral interventions to reduce suicide behavior: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Modif 2008; 32: 77–108.

- Mewton L, Andrews G. Cognitive behavioral therapy for suicidal behaviors: improving patient outcomes. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2016;9:21–29.

- Johnson J, Gooding P, Tarrier N. Suicide risk in schizophrenia: explanatory models and clinical implications, The Schematic Appraisal Model of Suicide (SAMS). Psychol Psychother 2008; 81(Pt 1); 55-77.

- Tarrier, N., Gooding, P., Pratt, D., Kelly, J., Awenat, Y., Maxwell, J., 2013. Cognitive Behavioural Prevention of Suicide in Psychosis: A Treatment Manual. Routledge, London, UK.

- Tarrier N, Kelly J, Maqsood S, Snelson N, Maxwell J, Law H, et al. The cognitive behavioural prevention of suicide in psychosis: a clinical trial. Schizophr Res 2014; 156: 204–10.

- Pratt D, Tarrier N, Dunn G, Awenat Y, Shaw J, Ulph F, et al. Cognitive behavioural suicide prevention for male prisoners: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med 2015; 45: 3441–51.