Written by Hannah Clayton, Honorary Research Assistant, CARMS Project

The CARMS (Cognitive AppRoaches to coMbatting Suicidality) Project[1] focuses on testing the efficacy of a new psychological therapy to help reduce suicidal experiences in people with psychosis. In the last CARMS blog, we spoke about the effects of stigma surrounding suicide. Within this, we touched upon the subject of gender identity and how this may disproportionately affect some people’s experiences of stigma. Continuing with our monthly blog, we thought it was important to now share more information on gender identity in the context of mental health and suicidal experiences.

Gender Identity definitions

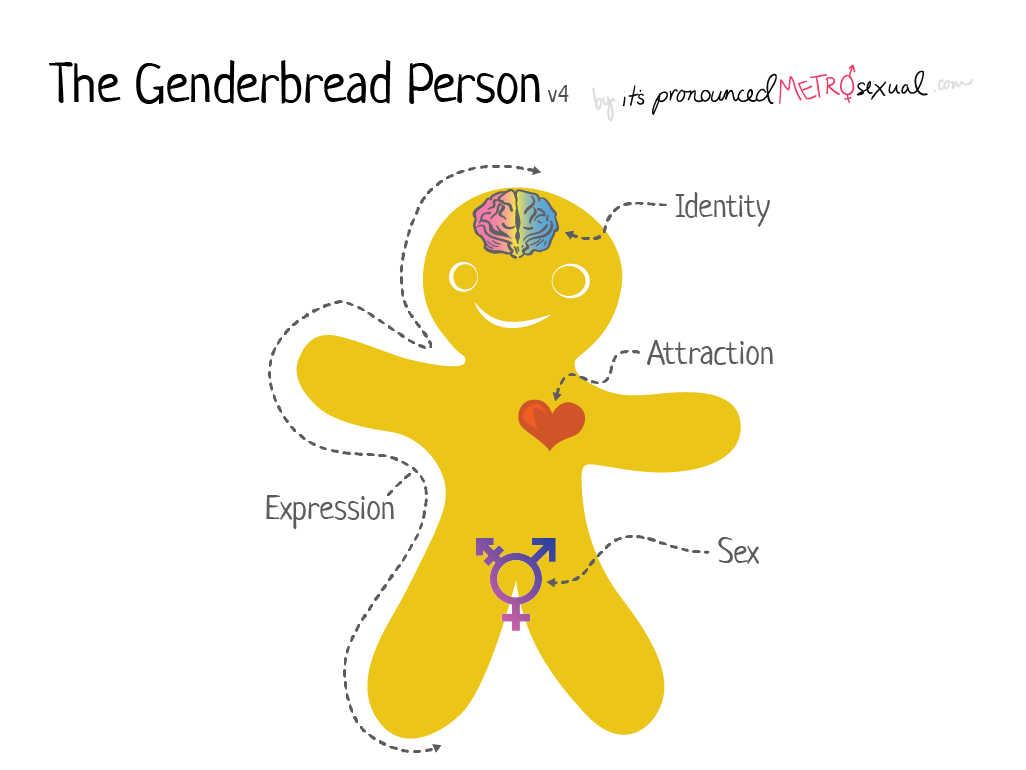

Gender identity is how people choose to describe their own gender. For example identifying as a woman[2]. Gender expression is how people choose to express their gender identity, such as through appearance and/or behaviour. This is different from sex, which is related to biology. Sex is also separate from sexual orientation which defines who people are sexually attracted to, for example bisexual or pansexual[3]. One way to understand the differences between these terms is with the ‘Genderbread Person’ diagram:

More information on this diagram can be found on The Genderbread Person website.

When talking about gender, there are lots of different labels or identities people may use, which are constantly changing and developing. Some examples include:

o Trans/Transgender: when an individual’s gender identity or gender expression is different from the gender or sex assigned at birth[4]. For example, a transgender person may identify as a woman even though they were born with male genitalia.

o Cisgender is rather when an individual’s gender identity matches their birth sex[5].

o Non-binary / genderqueer: when you do not feel like you are male or female. You may rather be a combination of the two or at times one or the other[6].

o AGenda / gender neutral: when you have no, or very little, connection with the concept of gender or may see yourself as not having a gender[7].

o Androgynous: a gender expression that has elements of both traditionally feminine and masculine traits[8].

o Gender Fluid: when your gender changes over time and you do not have a fixed or single sense of gender[9].

There are also other labels and terminology and some people may not choose to identify with any one of these. It is important to remember that all of these are valid. For more information, you can explore a comprehensive list of LGBTQ+ vocabulary definitions.

Suicide rates and mental health problems in the LGBTQ+ community

In 2018, the charity Stonewall carried out a survey to assess differences in experiences of life in Britain for LGBT people[10]. It was found that almost half of the people who identified as transgender (46%) thought about taking their own life in the past year; 60% thought their life was not worth living; and 12% had made a suicide attempt. In addition, the survey found that 41% of non-binary people and 35% of transgender people had self-harmed in the last year. Furthermore, 67% of transgender people and 70% of non-binary people had experienced depression in the past year.

These statistics highlight how common suicidal experiences are in individuals who identify as transgender and non-binary. By comparison, it is estimated that around 20% of the general population experience suicidal feelings in their lifetime[11] and around 13% self-harm[12]. Therefore, transgender and non-binary people are at a much greater risk of a range of suicidal experiences, as they face mental health problems and suicidal experiences at significantly higher rates than the general population[13].

Unique Risk Factors

Certain factors that increase the risk of suicide may particularly affect the transgender and non-binary population. These factors include:

o Discrimination. This may be in the form of physical or verbal harassment, as well as physical or sexual assault. A survey by Stonewall found that 41% of transgender people and 31% of non-binary people have experienced a hate crime because of their gender identity[14].

o Healthcare inequalities. Access to health-care tends to be particularly vital for transgender people, especially for those who choose to medically transition through surgery or hormone therapy. However, many of these individuals experience discrimination in healthcare settings. For example, a recent BBC article reported there were over 13,500 transgender and non-binary adults on waiting lists for NHS gender identity clinics in England[15]. The average waiting time is 18 months and some people even reported having to wait three years before their first appointment. Furthermore, transgender people have reported stigma and discrimination form health care professionals, as some individuals have even been given inappropriate or abusive treatment because of their gender identity, or even refused treatment altogether[16].

o Gender-appropriate spaces. Female- and male-only areas, such as bathrooms or changing-rooms, discriminate against transgender and non-binary people who may be denied access to these. One study found that denial of access to gender-appropriate housing and bathrooms across college and university campuses increased suicidal experiences[17]. In addition, a survey by Stonewall found 48% of transgender people do not feel comfortable using public toilets and some people reported experiencing physical, verbal and sexual assault in these public spaces[18].

o Transitioning. Choosing to medically transition, through surgery or hormone therapy, may cause stress and even increase the risk of suicide[19]. One study analysed the opinions of transgender people as they progressed through the transitioning stages[20]. Before transitioning, participants reported feelings of worthlessness, failure and discomfort. During the transitioning process, some individuals reported increased distress due to a lack of social support, rejection and discrimination. Yet in the post-transition phase, individuals felt a greater sense of comfort in their identity, peace and contentment. They also demonstrated more excitement and hope for their future life. Another study also suggested transitioning can greatly reduce suicidal experiences, as they found 67% thought more about suicide before transitioning, whereas only 3% thought more about suicide after[21].

o Bullying. Young people may face further discrimination in the form of bullying at schools due to their gender identity. One survey by Metro Youth Chances found 83% of young transgender people experienced name-calling, 35% experienced physical attacks and 32% missed lessons due to fear of discrimination[22].

How to help

If you want to offer support to communities and individuals who identify as transgender, non-binary or gender-diverse then there are some small steps you can consider taking:

o Use pronouns correctly. People will have preferred pronouns, such as they/them/their, her/she, he/him. It is important to use each individual’s desired pronoun choices and not assume what their pronouns are. If you are unsure, the organisation GLAAD has suggested that sharing your own pronouns first is a good way to bring up the topic. If you accidentally use the incorrect pronouns, you should explicitly and genuinely apologise then correct yourself[23].

o Be considerate about what questions you ask. Certain topics, such as questions about medical transitioning, sexual activity or life pre-transition may not be appropriate to ask someone[24]. For example, asking individuals what their “real name” or birth name is can create a lot of unwanted anxiety or stress[25]. It is important to be sensitive around these topics in order to treat every individual with respect, no matter how they choose to identify.

o Continue to create nurturing environments. It is important to have spaces where everyone feels comfortable. Creating these environments will allow people to feel safe and able to openly share their views or feelings about topics including gender identity and sexual orientation.

Where to find support

These are some resources that may be helpful:

o Stonewall is a charity offering help and advice to LGBT communities. Their information-service lines are open from 9:30 – 4:30, Monday to Friday: 0800 0502020. More information can be found on their website: https://www.stonewall.org.uk/help-and-advice

o IMAAN is a charity that supports Muslims who identify as LGBTQ+. You can contact them on imaanlgbtq@gmail.com and find more information on their website: https://imaanlondon.wordpress.com/about/

o Gendered Intelligence is a charity which aims to increase understandings of gender diversity and improve the quality of life of young transgender people in particular. They run youth groups across the UK and offer resources to help support transgender youth and their families. More information can be found on their website: http://genderedintelligence.co.uk/support/trans-youth

o Mermaids is charity offering family and individual support for young people who are transgender or gender-diverse. Their helpline is open from 9am to 9pm Monday to Friday: 0808 801 0400. Text chat is available 24/7 for free crisis support: 85258. An online chat is also available on their website: http://www.mermaidsuk.org.uk/

If you would like more information about the CARMS Project please contact Charlotte Huggett by telephone: 0161 2710729.

* This article contains references to suicide that some people may find distressing so if at any point you require urgent support with your mental health please contact your GP, care coordinator or crisis team. Other help can be found here:

- Samaritans: Phone 116 123; Email jo@samaritans.org; Text 07725 90 90 90; Or visit your local branch

- Anxiety UK

- Self-Help Services: Online crisis support www.selfhelpservices.org.uk/the-sanctuary; Phone 0300 003 7029

- Rethink (Mon-Fri 9.30AM-4PM): Phone 0300 5000 927

- Saneline (4.30PM-10.30PM): Phone 0300 304 7000

- Mind (9AM-6PM): Phone 0161 236 8000 (local rates and mobile charges apply); Email info@mind.org.uk; Text 86463

- The University of Manchester Counselling Service

- The CALM Zone

- PAPYRUS

A bit about Hannah Clayton:

“I have been volunteering as an Honorary Research Assistant at the CARMS Project since June 2019. I have recently completed my BSc in Psychology at The University of Manchester, where I will officially graduate in the next few months. I completed an independent research project during my time here, on the factors influencing students’ help-seeking attitudes for mental health problems. My motivation behind this project came from my interest in how we can best support vulnerable groups of people to get them the help they need. I have also used this motivation in my work outside my studies. For example, I am a volunteer with Samaritans, who I have been with for almost two years now. I am a strong believer in their values and recognise the need to support people dealing with distressing situations, including suicidal experiences. I also hold a position with the charity ‘Reach-Out’ where I lead weekly after-school classes with young people, alongside their volunteer mentors, in disadvantaged areas around Manchester to help raise aspirations and growth in both attainment and character. My plans for the future are to carry on supporting others, especially young people, who may experience mental health problems and suicidal experiences. I am therefore very excited to be part of this blog series for the CARMS Project.”

References

[1] Gooding, P.A., Pratt, D., Awenat, Y. et al. A psychological intervention for suicide applied to non-affective psychosis: the CARMS (Cognitive AppRoaches to coMbatting Suicidality) randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Psychiatry 20, 306 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02697-8

[2] Stonewall Youth (2020). Gender Identity. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://www.youngstonewall.org.uk/lgbtq-info/gender-identity

[3] Kids Helpline (2020). Gender Identity. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://kidshelpline.com.au/teens/issues/gender-identity

[4] Stonewall Youth (2020). Gender Identity. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://www.youngstonewall.org.uk/lgbtq-info/gender-identity

[5] Stonewall Youth (2020). Gender Identity. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://www.youngstonewall.org.uk/lgbtq-info/gender-identity

[6] Stonewall Youth (2020). Gender Identity. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://www.youngstonewall.org.uk/lgbtq-info/gender-identity

[7] It’s Pronounced Metrosexual (2020). Comprehensive* list of LGBTQ+ vocabulary definitions. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://www.itspronouncedmetrosexual.com/2013/01/a-comprehensive-list-of-lgbtq-term-definitions/#menu

[8] It’s Pronounced Metrosexual (2020). Comprehensive* list of LGBTQ+ vocabulary definitions. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://www.itspronouncedmetrosexual.com/2013/01/a-comprehensive-list-of-lgbtq-term-definitions/#menu

[9] Gillespie, C. (2020, February 25). What does it mean to be gender fluid? Here’s what experts say. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://www.health.com/mind-body/gender-fluid

[10] Stonewall (2018). LGBT in Britain: Health report. Retrieved from: https://www.stonewall.org.uk/system/files/lgbt_in_britain_health.pdf

[11] Time To Change (2020). Suicidal feelings. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://www.time-to-change.org.uk/about-mental-health/types-problems/suicidal-feelings#toc-2

[12] Selfharm UK (2020). Self-harm statistics. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://www.selfharm.co.uk/get-information/the-facts/self-harm-statistics

[13] Centre for Suicide Prevention (2020). Transgender people and suicide. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://www.suicideinfo.ca/resource/transgender-people-suicide/

[14] Stonewall (2018). LGBT in Britain: Trans report. [Online report]. Retrieved from: https://www.stonewall.org.uk/system/files/lgbt_in_britain_-_trans_report_final.pdf

[15] BBC (2020, January 19). Transgender people face NHS waiting list ‘hell’. [Online new article]. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-51006264

[16] Whitehead, B. (2017) Inequalities in access to healthcare for transgender patients. Links to Health and Social Care Vol 2(1), pp. 63 – 76. https://doi.org/10.24377/LJMU.lhsc.vol2iss1article109

[17] Seelman, K. (2016). Transgender adults’ access to college bathrooms and housing and the relationship to suicidality. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(10), 1378-1399. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1157998

[18] Stonewall (2018). LGBT in Britain: Trans report. [Online report]. Retrieved from: https://www.stonewall.org.uk/system/files/lgbt_in_britain_-_trans_report_final.pdf

[19] Centre for Suicide Prevention (2020). Transgender people and suicide. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://www.suicideinfo.ca/resource/transgender-people-suicide/

[20] Budge, S., Katz-Wise, S., Tebbe, E., Howard, K., Schneider, C., & Rodriguez, A. (2013). Transgender emotional and coping processes: Facilitative and avoidant coping throughout gender transitioning. The Counselling Psychologist, 41(4), 601–647. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000011432753

[21] Bailey, L., Ellis, S., & McNeil, J. (2014). Suicide risk in the UK trans population and the role of gender transitioning in decreasing suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Mental Health Review Journal, 19(4), 209-220. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-05-2014-0015

[22] Beyond Bullying (2020). Transphobic bullying. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://www.beyondbullying.com/transphobic-bullying

[23] GLAAD (2020). Tips for allies of transgender people. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://www.glaad.org/transgender/allies

[24] National Centre for Transgender Equality. (2016, July 9). Supporting the transgender people in your life: A guide to being a good ally. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://transequality.org/issues/resources/supporting-the-transgender-people-in-your-life-a-guide-to-being-a-good-ally

[25] GLAAD (2020). Tips for allies of transgender people. [Online article]. Retrieved from: https://www.glaad.org/transgender/allies