Double Helix History extended our search for the impact of DNA on family and wider history to a 4th continent with a visit to the United States.

In a windy Plymouth, Massachusetts, it was a pleasure to receive a guided tour of the Mayflower Society headquarters, in many ways the “mothership” of American genealogy. A notable trend amongst American researchers that wasn’t as prevalent elsewhere was work towards membership of genealogical societies such as the Daughters of the American Revolution and the General Society of Mayflower Descendants. The pictures below include many volumes of meticulously evidenced and referenced family trees, to which an aspiring member needs to establish a well-supported ancestral link. Interestingly, one of our UK researchers is unable to join the Mayflower Soc because his link is only proven by DNA and not by paper records. This was yet another example of the issues we have been exploring in our research around the questions DNA generates around inheritance, identity, and historical truth – DNA could “prove” unrecorded links but also disrupt existing “proofs”, but does verified genetic descent really give a greater claim on identity or membership than other forms of personal or collective “inheritance”?

Thanks to the phenomenal assistance of the Washtenaw County Genealogical Society and many members of their thriving and growing Genetic Genealogy Special Interest Group, we had 2 lively and wide-ranging focus groups in Michigan, hosted very generously by Saline District Library and the University of Michigan’s beautiful Clements Library.

We found researchers who had made a wide range of discoveries, including breakthroughs on brick walls and links to branches not previously researched. DNA testing and research had allowed some individuals to trace parents and parts of their immediate family they were searching for and had never previously met while also unearthing some surprising findings for other individuals. We discussed many of the ethical dilemmas involved in approaching these types of situations, with researchers experiencing them from all angles – as searcher, those discovering links to unexpected family members, and those advising, counselling, and conducting research on behalf of others.

There was also a wide range of experience in using records across the United States and numerous other countries, as individuals traced family branches to other parts of the world and talked about the way in which this informed the way they thought about identity and the quirks of history.

We were also lucky enough to talk with members of the Fred Hart Williams Genealogical Society, a Detroit-based group dedicated to African-American history and family history. Among many topics, we discussed the radical impact that DNA was having in restoring histories and family trees obscured by traditional sources, both by a dearth of records and the repeated breaking up of families during enslavement and the demographic and geographic dislocations in the ensuing decades. Stories never recorded, lost, or passed down through families orally are now being reclaimed and pieced back together by researchers to be told within families and communities, but also disseminated and preserved more widely in publications and online. Many of these narratives and topics are, however, difficult for many individuals to discuss, but the restorative approach of researchers in having open and personal discussions about these themes, such as histories of slave ownership in families, can open a dialogue where individuals and communities can come to terms with painful histories.

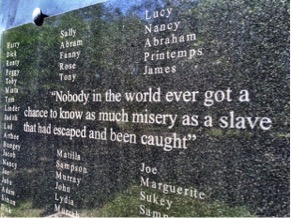

The Whitney Plantation in Louisiana gives a powerful exposition of the effectiveness of addressing complex narratives around enslavement head-on. Unlike most plantation museums, Whitney foregrounds the discovery, communication, preservation, and commemoration of the experiences of the enslaved individuals, through a series of powerful artworks, including a memorial of all known names of enslaved people in the region, compiled through decades of meticulous research, a memorial to the participants in the German Coast slave revolt, and specially-commissioned statues of the “children of Whitney”, those of the same generation whose oral testimony of enslavement was captured in the Federal Writers’ Project recordings of the 1930s which are used throughout the plantation.

The plantation are about to begin a genealogy project to trace the descendants of both the enslaved and non-enslaved residents of Whitney and other local plantations, a project which promises to demonstrate further the restorative power of family history and its impact on wider public understanding and collective memory.

Jefferson Parish Library were our kind hosts for our final two focus groups, where we had more fascinating discussions with a range of researchers, some of whom had been working for decades on their family histories, and some very recent “converts”. Among other topics, we talked about the recurring pattern of inconvenient records being lost or “burned in a fire”, only to be discovered on further probing by dogged researchers. We also talked about the importance of commemoration and legacy and the interesting ways in which DNA can allow names to be restored to tombs and untangle complex and poorly recorded family trees.

Our conversations in New Orleans brought our series of interviews and focus groups to an end for the present, with the work for the next few months being to draw together all of the experiences and insights we have gathered from our researchers for publication and discussion.