The LOTUS study is the largest ever study of the effects of water fluoridation on the dental health of adults.

Our study used real-world anonymised data on 17.8 million adults and adolescents who attended NHS dental practices in England between 2010 and 2020. We did this to understand the effect of water fluoridation on:

- the number and types of dental treatments received;

- the costs of those treatments to the NHS;

- the costs of those treatments to NHS dental patients.

For more information on the anonymised dental data that we hold, please refer to the Privacy Notice for our study.

Over 10 years, people receiving optimally fluoridated water experienced a 3% reduction in NHS invasive dental treatments such as fillings and extractions, and a 2% reduction in the number of decayed, missing, and filled teeth, compared to those who received non-optimally fluoridated water.

The research team found no compelling evidence that water fluoridation reduced social inequalities in dental health, and the numbers of missing teeth between the groups were the same.

Between 2010 and 2020, optimal water fluoridation cost £10.30 per person, NHS treatment costs were £22.26 lower per person (5.5%), and patients paid £7.64 less (2%) in dental charges.

We estimate that if 62% of the adults and teenagers in England attended NHS dental services at least twice within 10 years, the total return on investment would have been £16.9 million between 2010 and 2020. This means that the costs of water fluoridation were recovered, and £16.8 million saved on top as a result of lower NHS dental treatment costs.

This short animated video explains the study in more detail.

Academic publications

-

- Moore, D. et al. How effective and cost-effective is water fluoridation for adults? Protocol for a 10-year retrospective cohort study.

BDJ Open 7, 2021. - Nyakutsikwa et al. Water fluoride concentrations in England, 2009-2020. Community Dental Health 38, 2021.

- Nyakutsikwa, B. et al. Who are the 10%? characteristics of the populations and communities receiving fluoridated water in England. Community Dental Health, 39(4),247–253, 2022.

- Moore D, Nyakutsikwa B, Allen T, Lam E, Birch S, Tickle M, Pretty IA, Walsh T. How effective and cost-effective is water fluoridation for adults and adolescents? The LOTUS 10-year retrospective cohort study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2024 Jan 8. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12930. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38191778.

- Moore, D. et al. How effective and cost-effective is water fluoridation for adults? Protocol for a 10-year retrospective cohort study.

Full report

The full and final report of the study results will be available when it has been approved by a peer review panel.

You will be able to view it online at the LOTUS NIHR Journals Library.

Adding fluoride to the public water supply (fluoridation of tap water) has been strongly promoted by dental professionals since the 1950s. However, only about 10% of the people in England receive water containing close to the government’s recommended fluoride level of 1 mg/litre.

Fewer children now have tooth decay, and more adults keep their permanent teeth into old age. This is put down to using toothpastes that contain fluoride.

In the early 1970s, almost everyone experienced decay in their permanent teeth by late childhood, and more than a third of adults had no natural teeth. In comparison, today we have problems due to decay that is slowed down but continues to progress through to late adult age instead.

For many people, this means repeated dental surgery visits, tooth drilling, filling and extractions, and the final outcome may still be complete tooth loss. During periods in between, there can also be varying levels of pain, anxiety and financial loss, making life miserable.

Wider use of water fluoridation is thought to be a practical, low-cost public health measure that could offer lifetime benefit in combating this slower form of adult tooth decay. However, little evidence for or against this in adults has been published, which is why our study of anonymised NHS dental care patient data was proposed.

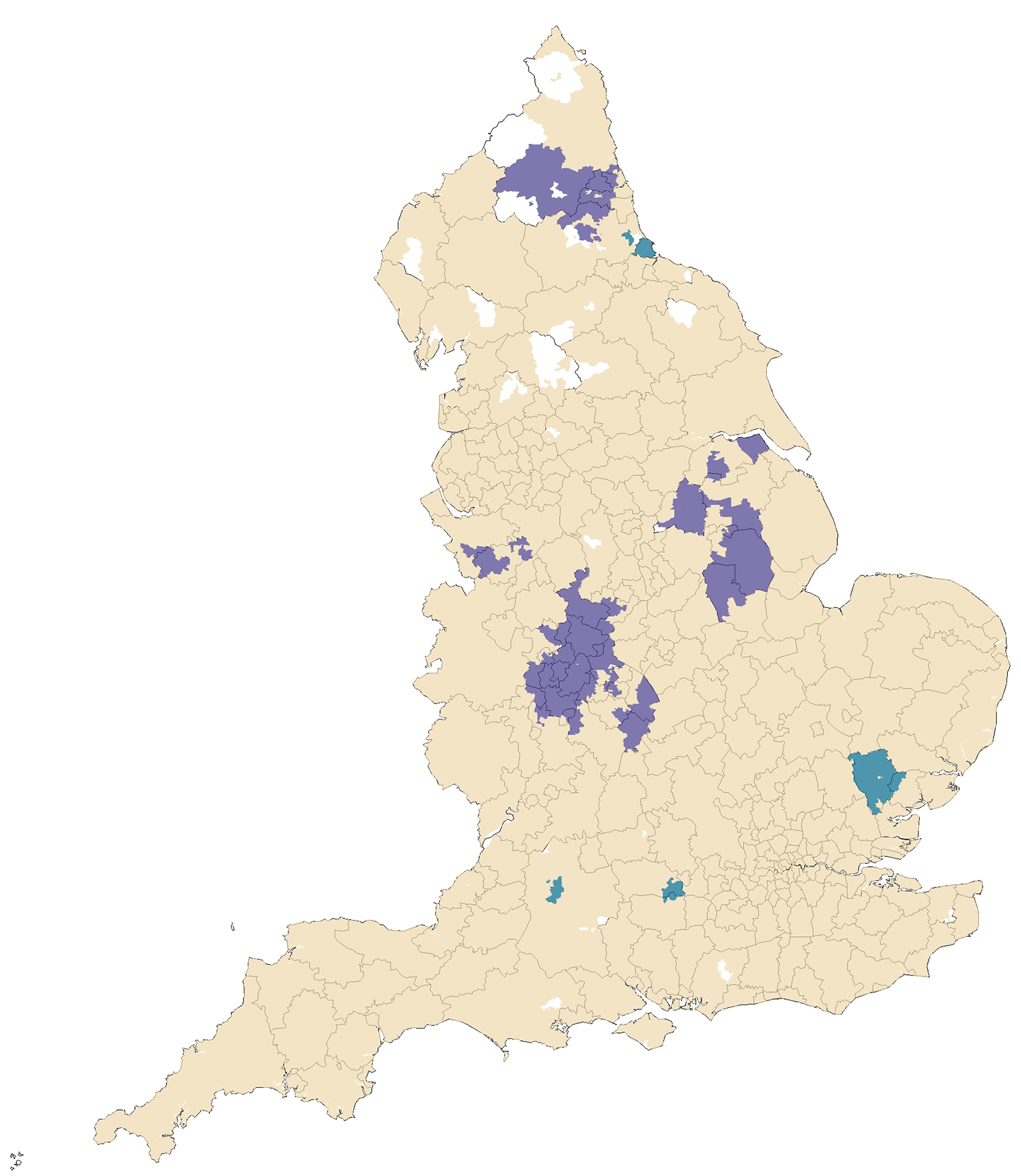

The map below shows the small neighbourhood areas (LSOAs, covering around 1,500 people) that received fluoridated water between 2010 and 2020.

Areas that received water with a fluoride concentration of 0.7 mg fluoride / litre or above are highlighted. The local authority boundary lines are illustrated. Areas that are coloured white are those where we did not receive any sample information from the water companies.

Local authorities in which all of their neighbourhoods were fluoridated during this time were:

- East Staffordshire;

- Lichfield;

- Cannock Chase;

- Tamworth;

- Birmingham;

- Sandwell;

- Dudley;

- Bromsgrove;

- North Kesteven;

- Newcastle upon Tyne;

- Hartlepool

The water in Hartlepool has naturally higher levels of fluoride. This comes from the rocks that the water passes through.

![]() Fluoridated

Fluoridated

![]() Naturally Fuoridated

Naturally Fuoridated

Not Fluoridated ![]()

This is the first time that such detailed information on fluoride levels in England has been available.

We have made the data that we created on water fluoride concentrations publicly available. It can be used by other researchers under a creative commons license. This means that the data can be shared and adapted with appropriate attribution.

The dataset can be downloaded from The University of Manchester’s Open Data Repository, Figshare.

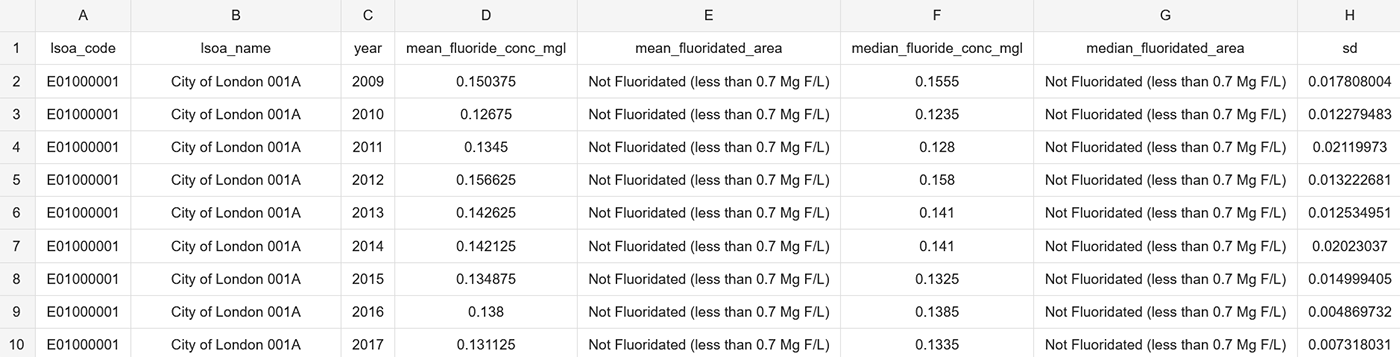

The information available includes:

- LSOA 2011 code, LSOA 2011 name, year, and mean and median fluoride concentrations per year (in milligrams of fluoride per litre).

- An indicator for whether an area was ‘fluoridated’ in each year, using a water fluoride concentration of 0.7 Mg F/L and above.

The image below shows a snapshot of the dataset that can be found in the Figshare open data repository.

This study is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research: NIHR128533.

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

The study started on 1 February 2020 and is set to submit results to the funding committee, NIHR, on 31 July 2022. This includes a 6-month extension to the study due the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ms Deborah Moore, Research Associate

Email: deborah.moore-2@manchester.ac.uk.