The View from the Cloakroom

Paris’s Stock Exchange – the Bourse – was the heart of the second largest financial market in the world down to the Great War. It trailed London in terms of the volume of transactions it hosted, but was nevertheless similarly international, with a privileged position as a market for international public debt. Along with the third and fourth place markets of Berlin and New York, and thanks to the rapid expansion of its massive commercial banks, Paris was a strategic centre channeling the flows that constituted capital’s first era of globalization.

Photograph of the Paris Bourse, early twentieth century. Source: Archives de la Préfecture de Police de Paris, D/B 188.

Despite its global footprint, the nineteenth-century Bourse was also distinctly and importantly Parisian. Not only were the microstructures of the exchange – the rules of trading and the regulations governing agents – distinct from other national exchanges. (These rules made information generated on the Bourse an entirely different kind of commodity from that springing from the London or New York exchanges.) The exchange was also Parisian in a legal sense. Built by the architect Alexandre-Théodore Brogniart along designs approved by Napoleon, it became the property of the city of Paris in 1829. It was a municipal asset that brought in around 240 000 francs to the city’s coffers annually at the turn of the century. (When a 1fr entrance fee was imposed between 1856 and 1861, it returned 617 000 francs per year.) The city’s police had a special division dedicated entirely to the exchange and to controlling places where brokers conventionally gathered, tracking the curb market and other unofficial trading groups through cafés, passages, and club rooms near the official exchange.

Since at least Saskia Sassen’s now classic work Global Cities, local spaces and material assemblages are acknowledged as crucial to seemingly disembodied networks of global finance. In the nineteenth century, exchanges became icons of urban and financial modernity, their confusing crowds instantiating otherwise invisible relations of money and trade. At the same time – and as is the work of icons – their spectacular imagery obscured the ordinary and routine work that assembled financial transactions into international markets.

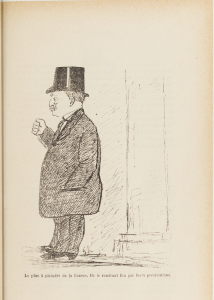

A portrait of Lévy from her book, La Bourse en 1890.

This labour is not invisible to all – certainly not to those who perform it. Taking sidelong or unfamiliar views can help push aside the tropes of the temple of money and reinvigorate our understanding of the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of financial markets.

This particular view comes from the cloakroom. The Paris Bourse had at least three, one at each entrance, where men with business on the exchange consigned their hats, jackets, umbrellas, canes – anything that might encumber their activities during trading. (At some points, turning over umbrellas and canes was obligatory, to avoid the temptation of their aggressive deployment inside.) They were leased to concessionaries by the City of Paris, and all were run day-to-day by women – the only women permitted inside the Bourse, which was open only to those who enjoyed their full political rights. In 1889, one of their occupants, Nathalie Lévy, penned a unique guide to the men and spaces that made up the Bourse, one that defied convention by individualizing its participants and by widening its scope to include not only the flurry of tail-coated transactions that typically dazzled observers but the work of maintenance, surveillance, and support that surrounded the hubbub of finance.

Lévy’s Exchange

Among popular guides to the Bourse, Lévy’s not only stands out for being written by a woman and a worker at the exchange. It is deeply idiosyncratic, eschewing the official agents and spaces of the Bourse in favour of its employees, independent intermediaries, and service spaces. Even the familiar portion of the book – an almanac-style section listing the city’s principal banks and brokers – is uniquely developed, listing hundreds of smaller agencies in multiple lines of business “concerned with finance” alongside financial heavy weights like the Bank of France and the Crédit Lyonnais. The world of Lévy’s Bourse is sprinkled across the city, from single-room brokerages to multi-branch financial department stores.

The author’s chief interest comes in a humorous catalogue of Bourse denizens, brought to life by sketches from well-known illustrators. Lévy draws verbal ‘silhouettes’ of dozens of individual intermediaries – like the remisiers who shuttled business between clients, brokerages, and official stock brokers – offering teasing and pun-filled descriptions of their appearance, business, and temperament. Where most ‘physiognomies’ populate the Bourse with types (the bull, the bear, the winner, the loser), Lévy introduces us to people – for example, to Léon Weil, who used to work for Pereire but today trades for the Dreyfus bank; to Ernest Morel, a trader in the curb market who has two clerks just to sort his telegraph messages (and for all that gets impatient if a moment passes without more news); to Clavelly, who can claim a self-made fortune; and to Poloniny, a “créole by birth” and “the prettiest boy at the Bourse.”

Bonhomie at the Bourse: An unsuspecting trader is the butt of his fellows’ jokes, fearing what they place in his pockets.

Light-hearted and playful, the guide catalogues a fraternity of fair sport, even-handedness, and good intention. From the rowdy coulisse (the curb market) to the middlemen of the official exchange, Lévy’s Bourse is a marvel of good faith and honesty, “trafficking in millions” with nothing but a pencil tick. Slow moments are given over to harmless fun and innocent escapades – “gamineries” (childishness) like slipping a live crayfish into someone’s pocket – all while sharing around chocolates and candies. (Lévy purportedly sold sweets from her perch in the cloakroom.) In the place of a nefarious network or impenetrable tumult, Lévy gives us charming personalities and boys being boys, a simplicity and jocularity that humanizes and entertains. Professional money-making jockeys with professional pleasure-taking in descriptions that give more space to horse-racing, yachting, and concert-going than to financial operations.

If this world is like any other, it is the world of the theatre. (Lévy’s book is published by the Revue théâtrale illustrée, edited by her father, Léon, who was also the concessionary of the Bourse’s cloakrooms.) We learn that Jeaques Kann’s pencil “serves two ends: for prices on one side of his paper, and portraits on the other;” that Colaço, a specialist in arbitrage, “looks shockingly like Rochard, director of the Ambigu Theatre” and that the banker Raphael looks like “Colonne, director of the Châtelet’s concerts;” that the remisier Gans never misses an opening night and that André Wolff married the daughter of a singing sensation from the Opéra-Comique.

Maintenance and caretaking workers at the Bourse, 1924. Source: BNF, Agence Rol.

The name of the unofficial market, the coulisse, also refers to the wings of a theatre, and Lévy’s account expands from the supporting cast of traders to those behind the scenes. She introduces readers to the people responsible for maintaining the building, running the cloakrooms, writing up official prices, and securing order. The agents from the local police detachment, called upon to control crowds and settle disputes (Lévy puns that “discussions of a very delicate nature are often liquidated in [their] office”), along with the twenty-two guards (black uniforms with silver braid) managed by brigadier Rémond and attached to the official stockbrokers, and the building’s eight caretakers (blue coats and red epaulettes), render “important services” to the business of trading. It was the concierge, M. Cottin, we learn, who saved the building and its archives during the Commune – indeed, the Bourse’s police detachment records are the only local commissariat archives to survive the fires of the siege and Commune. She lingers, too, on the material that makes the Bourse tick: how chairs are rented and moved about, how movable writing surfaces were designed and installed, how telegraph cables were transferred via secure bags and fleets of running or cycling clerks.

View from the Wings

We have Lévy’s positionality to thank for this attunement to the overlooked work of care, maintenance, and support in the life of the Bourse. At least briefly an actress (newspapers report favourably on some stage appearances in 1891 and 1892) and connected to the theatre through her father, she was familiar with the vast operations of a mise en scène. As a service provider at the exchange, we can imagine a daily routine of observation from her counter at the cloakroom, in the wings of the Bourse’s central dramas. It is easy to picture the lulls between harried moments of arrivals and departures, when security guards, cleaners, and unoccupied clerks pitched up at Nathalie’s counter to gossip and crack jokes, possibly at the expense of self-important financiers. Her position as a woman accentuated this remove. The book’s tone is maternal, indulgent and gently mocking. (I don’t know Nathalie’s age for certain at this point, but it’s likely she was in her late forties.) Reviewers uniformly commented on the (agreeably) feminine nature of the text; Le Grélot described the author as “enormously parisienne,” an adept “of the art of scratching without piercing the skin.”

A sketch of Nathalie Lévy at the cloakroom of the Bourse, from La Presse, 1900.

Critics skewered her in both gendered and antisemitic terms. The cloakroom, where traders partially disrobed to better maneuver (coat, hat, boutonniere, and gloves discarded, so that “one would no longer recognize the elegant man about town”) lent itself to much innuendo. One retrospective from La Presse in 1900 described her as having transformed a simple attendant’s role into a lucrative salon – turning up when she felt like it, decked out to the nines and holding court with traders up for intrigues…sous le manteau (illicit dealings – literally: under the coat). On the one hand, “she symbolized the cult of the feminine, a reminder of romance and rest in the midst of the deafening racket, the brutalities and mêlées of the money traffickers;” on the other, the journalist suggests, she earned the nickname ‘Madame Putiphar’ for her alleged liaisons. Hers were the illicit pursuits of a woman out of place and a “well protected Jewess,” replaced in her turn by “another, no less pretty and no less Jewish, freshly divorced and adorably blonde.”

Indeed, the only part of her book to receive serious engagement in the press was an assertive section defending Jewish financiers from the period’s rampant antisemitism. Noting that readers will have noticed that “children of Israel” occupy a significant place in “the temple of speculation,” she praised Jewish finance – “this haute banque that so obsesses Drumont” – not only for sustaining the market in public debt and national securities but for putting thousands to work – the employees, building caretakers, and telegraph boys she’d just introduced by name. While the press obsessed over the smallest infractions if they happened to be committed by a Jew, she wrote, it entirely overlooked their immense works of charity. She flagged the contributions of Jewish women particularly, pointing out that two of the only five women ever to be awarded the Legion of Honour were Jewish. This section was excerpted at length in Le Grélot, a weekly illustrated magazine, and the author disparaged for being insufficiently objective about her fellow Jews, whose “manias” prevent non-Jews from treating them as countrymen. Yet the entire book, with its sketches of business bonhomie and layers of worthwhile labour, can be read as an effort to celebrate and normalize an increasingly demonized group.

Nathalie Lévy’s text gave her a buzz of publicity in the early 1890s, after which – and after the death of her father, in 1892 – she seems to have dropped from the public eye. But her unconventional guide to the Bourse, informed by her status as a woman, Jew, and worker located simultaneously at the heart and on the margins of the icon of finance, opens far more informative vantages on the work and location of finance than she surely intended when penning her comical anecdotes. In most respects, this is not a serious book; it’s a piece of gossip, a work of advertising, a grab at some headlines and salacious repute. And yet it reveals much of the daily world of market-making, and helps us recover the mundane, material, and embodied aspects of financial enterprise that both shaped its development and informed its cultural and economic significance.

Further Reading

- Youssef Cassis, Capitals of Capital: A History of International Financial Centres, 1780-2005 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006)

- Pierre-Cyrille Hautcoeur and Angelo Riva, “The Paris Financial Market in the 19th Century: Complementarities and Competition in Microstructures,” Economic History Review (November 2011): 1-28

- John Handel, “The Infrastructures of Modern Finance: The Rise of Stock Exchanges in Britain and its Empire, 1800-1929,” PhD dissertation in progress (UC Berkeley, History)