Monuments to Financial Crisis

Space matters tremendously to both the reproduction and the everyday experience of finance, something which did not elude contemporary financial operatives and their critics in nineteenth-century France. The premises of a financial outfit was worth investigation and investment by all concerned. Police examining potential malfeasance accorded great significance to what could be gleaned from the location of an agency, the rent it paid, the organization of its rooms, and the circuit of people they housed. An inquiry into the Crédit Territorial de France in 1882, for example, emphasized that the setup of its offices proved without doubt that the company was linked to two others, as “all the rooms connect between them, without appearing so to the public.” The arrangement of what purported to be an administrative council chamber, hung with cherry satin and dominated by an immense table covered with green felt, “gave the room an administrative appearance that might impress a naïve public.” But, the report continued, “the furnishings give more the atmosphere of a gambling house than a council chamber; the great, double-door deposit box, covered with dust and rarely opened […] An experienced eye can tell in a glance that everything breathes deception.” Space could communicate an intention to mislead, and was a central category of economic surveillance.

Cover of the anonymous 1884 exposé of the Crédit de France, a “bank” (a scam?) that collapsed from 1882.

When the Crédit de France, a large-scale but unstable (and ultimately, fraudulent) banking enterprise was ruined along with scores of similar companies in 1882, exposés like the anonymous Grandeur et décadence d’une société financière [Rise and Fall of a Financial Company, 1884] were full of contempt for the way such firms embedded themselves in cities across France, and especially how they aimed to engage the public by doing so: “Let us pick any of the country’s larger cities; choose the richest district, the most monumental building; there, on the first floor, you’ll be sure to find that kept woman known as the Crédit de France. Its name stretches in huge golden letters across the balcony’ drawing in customers, its 30 million making eyes at passers-by, who are incapable of resisting the outpouring of the prostitute’s charms.”

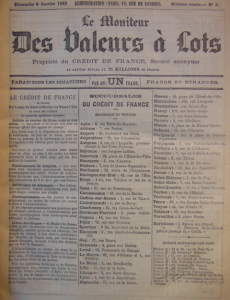

Front page of the Moniteur des Valeurs à Lots, listing all the company’s branches in France. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, photo by author.

This company was in existence for just slightly over five years, and yet its directors – or, more accurately, Edouard Lepelletier, the disgraced banker who was pulling the strings – spent a considerable part of that time on the construction of a luxurious headquarters in the dynamic commercial districts of Paris’s right bank. It’s hard to fathom how quickly and ostentatiously this firm, raking in terrific sums of money from clients who avidly consumed its cheap gazette, the Moniteur des Valeurs à Lots, marked their stake in the fevered Parisian financial scene of the early 1880s. The building erected at 16 rue de Londres was across the street from the company’s original headquarters at no.17, and intended as a showpiece for the public (the company kept offices and meeting spaces at no.16). As a statement about the firm’s growth, optimism, and self-importance, the expansion far outpaced the short distance involved.

The new building was constructed by Salomon Revel, an architect also employed by the capital city’s police prefecture. It received warm reviews, many of them pushed in a massive press campaign by the bank, and stands out today for distinctive – perhaps not entirely harmonious – ornamentation. The British journal The Builder noted the grandiose Renaissance façade but chiefly praised the interior decoration, which included gilded mosaics, wide stone staircases with wrought iron handrails, and large ceiling frescos by the artists Henri Gervex and A. Louis Rey. Gervex in particular was an acclaimed young painter; his picture Rolla caused a scandal when it was banned from the Salon in 1878 for immorality, but he quickly found a place as a nearly official painter of municipal republicanism. At 16 rue de Londres, the painter depicted (or, alternatively, Rey, a ‘painter-decorator’ copied) an allegory of the bank on the ceiling of the gilded, Louis XVI style administrative council chamber. The painting depicts a female form bearing a caduceus – symbol of Mercury, the mythological messenger and protector of merchants – and surrounded by the accoutrements of finance (account books, a bill press, a safe), industry (smoke stacks) and global commerce (Chinese porcelain, textiles).

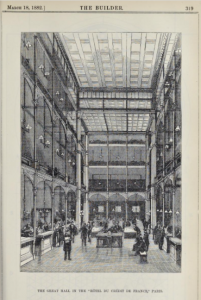

Alongside these trappings of augustness, the bank invested in the infrastructures of transparency and security that defined the new commercial banking establishments of this period. As The Builder noted, “The Hall is devoted chiefly to the financiers, who are in constant communication with the public”, surmounted by – and exposed to – three ranges of galleries supported by iron columns and girders. The French press repeated that the vaulted hall rises “hardiment” – a word that translates as both “boldly” or “recklessly.” The bank’s (read: clients’) capital was reputedly protected by “deeply excavated” basements – home to vaults and deposit boxes – and a system of fire prevention that could “inundate a considerable portion of the building” with one turn of a key. The sumptuous offices of the directors were “in direct communication” (L’Univers illustré, January 1882) with the public-facing bureaus, via electrical and compressed air mechanisms.

Interior of the Crédit de France, from The Builder, January 1882.

Certainly, the ceiling paintings and other surviving decoration give the building a certain attraction, resulting in some prominence in local historical tours and web reviews. Ordinary passersby cannot enter, of course – a stark contrast with the openness and exchange for which its monumentality was designed – though inaccessibility perhaps amplifies the interior’s allure. But such repute as building enjoys is, I suspect, generated rather by the fact that it was occupied for only one year before the Crédit de France went bust. The contrast between the opulent and declarative premises, festooned with a bombastic pastiche of columns and sculpted lions, and the nearly immediate collapse of the enterprise whose ambition it announced coalesces into an unsettled but affecting emotional assemblage: wonder, chagrin, schadenfreude. The attraction of the Titanic. The building was quickly repurposed by another company and is still in use today as commercial offices; its fall outside the financial economy was brief. But, in another register, it is nearly a ruin: a trace of grandeur and pomposity, a projection of an economic future that wasn’t, Ozymandias’s face in the sand.

The most important economic futures that were erased with the bank’s failure were those of its clients, which transpired at a remove from these vaunted, vaulted spaces. Lepelletier’s enterprise – named in succession the Crédit Français, the Société Générale Française de Crédit, and finally the Crédit de France, a name bought from another failing bank – was nicknamed in financial circles the “Petit Mazas” or “Maison Centrale de la rue de Londres,” in reference to the clandestine director’s convictions and prison sentences. Lepelletier was both skilled and politically savvy, painting his enterprise as royalist and Catholic in order to appeal to the same demographic that engaged with the Union Générale bank. Police reports described his bank’s gazette as “the example par excellence of a financial paper that defrauds the public with the most extraordinary bad faith, while knowing how to cleverly avoid falling afoul of legal infractions.” The transfer in late 1881 to the new headquarters was accompanied by a massive increase in subscribed capital (up to 75 million francs from only 6.5 million in early 1880) and a reshuffle of the administrative council, with famous and esteemed individuals replacing less notable (though possibly more notorious) characters. The building’s tiered interior may have unconsciously appropriated the criticism that many reputable financiers still lobbed at Lepelletier’s venture: that it was nothing but a “Bazar”, a “Louvre department store” or “Bon Marché de la Banque.” Just before its collapse, another police report noted that the bank “installed in unprecedented luxury on the rue de Londres” was nevertheless “on the point of collapse – the ruins will be immense.”

The refined exterior and grand offices of the Crédit de France. From Le Monde Illustré, January 1882. Source: BNF, Gallica.

Indeed, the building would remain as the company’s promises and aspirations evaporated. As the anonymous “gogo” wrote in 1884, by that point the building’s headquarters “were the only material flotsam that remained of this stupendous shipwreck.” Ruined investors began holding tumultuous meetings to discuss possible action against the company in mid-1882, gathering in meeting halls in the financial district. We can only surmise how the gilded interiors of the nearby Crédit de France appeared to them at this point. To some degree, they may have provided reassurance, tangible proof of the continued potential of the company as options were considered to right the boat; proof, as well, that they were not unwise to have invested with the company materially, of course, it represented a security that could be recovered by creditors. Though here, again, was frustration; the bank’s furnishings carried an auction estimate of 300 000 francs, but police reported that Lepelletier made his own deal, selling the lot to an interior decorator for just 35 000 francs but pocketing a 15 000 franc commission.

Nothing today announces this building’s status as a ruin, or perhaps a tomb, of financial aspiration. Yet clearly something lingers, a disjuncture created by the collision between castles in the air and durable stone and marble. The bank’s short-lived tenure endows the building with the fluidity of crisis; it was an imaginary of a state – for its builders, for its clients – that did not come into being. As we look for ways of accessing and theorizing the everyday world of finance, these spatial arrangements and built orders are centrally important. They not only told tales of affluence, of security, of modernity to investors – tales that could be read at a distance through publicity and reporting. They also engaged them physically in spaces of abundance and of performance: abundantly decorated, abundantly open, abundantly consumerist. We can not only discern contemporary expectations of investors – a group to be courted, dazzled, and made into participants in a bank’s story of itself – but also get closer to an investor’s experience of economic practices.

Further Reading:

- Youssef Cassis, Capitals of Capital: A History of International Financial Centres, 1780–2005 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006)

- Maria Kaika, “Architecture and crisis: re‐inventing the icon, re‐imag (in) ing London and re‐branding the City,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 35, no. 4 (2010): 453-474.

- Maren Koehler and Jasper Ludewig, eds., “Financialized Space,” Architectural Theory Review, special issue 26, no.1, forthcoming 2022

- Anne Murphy, “Performing Public Credit at the Eighteenth-Century Bank of England,” Journal of British Studies, 58, no.1 (2019): 58-78

- Grandeur et décadence d’une société financière, par un Gogo (Paris: Auguste Ghio, Éditeur, 1884)