Exploring autistic friendships at school & reflecting on setting up supportive environments

Research team: Charlotte Butter, Charlotte Alcock, Emily Randolph, Sarah Spurr, Alexandra Sturrock and Kathy Leadbitter

The research team are from The University of Manchester and the Paediatric Speech & Language Therapy Team, Manchester NHS Foundation Trust (MFT)

Background

A Patient & Public Involvement & Engagement (PPIE) project

Autism is a common form of neurodiversity (Kapp, 2020), typified by differences in social communication (DSM-5, 2022), which can impact upon interactions & friendships, particularly with people of a different neurotype (Williams et al., 2021). Positive friendships have been shown to increase self-esteem & reduce feelings of anxiety and depression (Buhrmester, 1990). However, autistic children are often unable to reap these benefits, reporting higher rates of loneliness & poorer quality friendships (Capps et al., 1996). Friendships with other autistic individuals are considered more accessible & easier to sustain (Crompton et al., 2020) increasing support networks, feelings of acceptance & self-awareness (Milton & Sims, 2016). However, opportunities to develop these friendships do not always occur naturally in childhood.

To date, few programmes have targeted the social communication needs of autistic teenagers (Marriage et al., 1995). MFT aimed to address that gap with a training package enabling schools to host social groups for adolescents. The training entailed two teacher-focused sessions (‘Autism from the other end of the lens’ & ‘Skills, ideas, resources & tips for setting up groups’) & one parent-focused session (‘Connect & continue positive relationships beyond school’). Ultimately, training could facilitate school-based social groups offering tailored but naturalistic environments for individuals to make friends & develop social communication confidence.

This PPIE project aimed to explore the lived-experiences of autistic young people in their attempts to make friends in school & sought their opinion on developing relevant and acceptable training materials (in line with co-production techniques, Farr et al., 2021)

What did we do?

We contacted local groups for autistic people by email & shared information about the PPIE project on social media. Interested people filled out an online form about themselves. We were aiming for a representative mix of ages, genders & ethnicities. We chose volunteers aged 16-25 as they could reflect on recent school experiences that were likely to be similar to experiences of current pupils. Volunteers’ consent was gained & they were happy for us to share anonymised quotes. Ethics was not acquired as this was a PPIE project rather than a research project. Staff & students from The University of Manchester interviewed volunteers online by video, chat or written form. Transcripts of interviews were analysed thematically to find common themes – experiences or ideas that were shared by several volunteers.

Who took part?

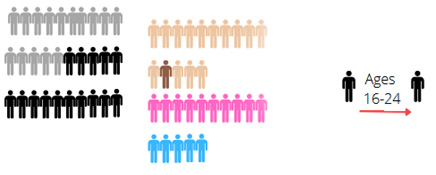

30 people signed up and 15 participated.

30 people signed up and 15 participated.

14 were White, 1 was Black African or Caribbean British.

10 were female, 5 were male.

Ages 16 – 24.

What did our volunteers tell us?

Findings showed that the opinions of autistic young people were essential in developing a resource & training package for teenagers in schools. Themes from the analysis showed a need for specific physical environments, certain structures for activities & an inclusive attitude of facilitators. They also indicated a need for unforced, naturalistic opportunities for developing social interactions & friendships (see below for more details). Findings also indicated that training for professionals running the groups should include autistic people telling their story. Content should also include: training about variation in presentation & preferences between autistic individuals, especially in less well recognised groups (e.g., in girls), the effects of anxiety, differences in friendship motivation, managing the sensory environment & neurodiversity acceptance.

Findings showed that the opinions of autistic young people were essential in developing a resource & training package for teenagers in schools. Themes from the analysis showed a need for specific physical environments, certain structures for activities & an inclusive attitude of facilitators. They also indicated a need for unforced, naturalistic opportunities for developing social interactions & friendships (see below for more details). Findings also indicated that training for professionals running the groups should include autistic people telling their story. Content should also include: training about variation in presentation & preferences between autistic individuals, especially in less well recognised groups (e.g., in girls), the effects of anxiety, differences in friendship motivation, managing the sensory environment & neurodiversity acceptance.

Intimate spaces

- Smaller and quieter spaces improve interaction.

- Fewer people can help build relationships.

“I think on a one-to-one basis. It allows me to be more personal and open with that person.”

Support needs

- Clubs related to activity or interests.

- Support with communication barriers.

- Sense of belonging.

- Familiar format.

“If it was a club that attracted a more specific crowd with specific interests I would have known I’d be guaranteed to meet people with very similar interests to mine.”

Autistic friends

- Neurodiversity in the group is important.

- Not necessarily all autistic people.

- Shouldn’t be forced.

“I didn’t meet another autistic woman until six months ago, like I’ve never even come across one before.”

Setting up a group

- Collaborative autistic working (young people).

- Community priority topics.

- Online options.

- Training to group providers.

“Having neurodiverse people involved in writing, presenting and any other part of the training process possible would be really good.”

What next?

Autistic young people in this PPIE project showed overwhelming support for the development of autism-affirmative training in schools & co-produced resources aimed at this group. They also provided important specific detail to guide the development of the programme, for example, encouraging teachers to establish groups around shared interests/activities with time for natural but supported interactions & relationships, hosted in small & quiet spaces. It indicates that the autistic community prioritise the development of knowledge & understanding of neurodiversity in teaching staff, parents, & other students. It suggests that this should include raising awareness of how friendships differ for autistic people & how these light-touch friendships & minimal interactions might be best supported.

This PPIE project demonstrates the importance of including autistic young people’s opinions & experiences in developing clinical materials. It ensures the programme will be more acceptable & applicable in line with general principles of co-production.

These findings have been presented to Manchester Foundation Trust, & will directly inform the development of a training package for teaching staff. The training package will create a supportive group for autistic high school students promoting acceptance, positive self-esteem, interactions, & relationships. The resulting package will be trialled & subjected to critical analysis using clinical research methods. The longer-term aim is to provide an evidence-based programme for working with this under-resourced group of autistic young people.

References

(1) Buhrmester, D. (1990). Intimacy of friendship, interpersonal competence, and adjustment during preadolescence and adolescence. Child Development, 61, 1101–1111.

(2) Capps, L., Sigman, M., & Yirmiya, N. (1996). Self-competence and emotional understanding in high-functioning children with autism. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 137–149.

(3) Crompton, C. J., Hallett, S., Ropar, D., Flynn, E., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2020). ‘I never realised everybody felt as happy as I do when I am around autistic people’: A thematic analysis of autistic adults’ relationships with autistic and neurotypical friends and family. Autism, 24(6), 1438-1448.

(4) APA (2022). Diagnostic Criteria for 299.0 Autism Spectrum Disorder. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/hcp-dsm.html.

(5) Farr, M., Davies, P., Andrews, H., Bagnall, D., Brangan, E., & Davies, R. (2021). Co-producing knowledge in health and social care research: reflections on the challenges and ways to enable more equal relationships. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8, 105.

(6) Kapp, S. (2020). “Introduction,” in Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline, ed S. Kapp (Singapore: Springer Nature), 1–19. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-8437-0.

(7) Marriage, K. J., Gordon, V., & Brand, L. (1995). A social skills group for boys with Asperger’s syndrome. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 29, 58–62.

(8) Milton, D., & Sims, T. (2016). How is a sense of well-being and belonging constructed in the accounts of autistic adults? Disability & Society, 31(4), 520–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2016.1186529.

(9) National Autistic Society. (2022). What is Autism? Retrieved from https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/what-is-autism.

(10) Williams, G. L., Wharton, T., & Jagoe, C. (2021). Mutual (mis) understanding: Reframing autistic pragmatic “impairments” using relevance theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 616664.

0 Comments