Professor Robert Lucas

Robert Lucas is the Director of the Centre for Biological Timing and GSK Professor of Neuroscience, in the School of Biological Sciences at Manchester.

Here, he talks about his lab, the Lucas Group, and their research into responses to light.

What does your lab specialise in?

The biology of light! We are fascinated by how mammals detect and respond to light, both for vision and as a way of coordinating biological rhythms.

Why does this area appeal to you?

Working with light is addictive. It’s a beautiful experimental stimulus that can be applied with very high spatiotemporal resolution and close control over quantity and spectral composition. Biological responses to light tend to be time delimited and satisfyingly reproducible.

Working with light also allows my lab to span the interface between vision science and chronobiology, two worlds with their own rich heritage, robust theoretical frameworks, and sophisticated experimental paradigms. What a privilege to stand on the shoulders of two sets of giants!

Furthermore, light is a very important aspect of our environment. Light has a powerful ability to both support and disrupt biological rhythms. Its influence extends to most body systems, including those responsible for intractable problems in public health such as insomnia, obesity, depression and anxiety. Yet we dose ourselves everyday with light from screens and light fittings with rather little care for these effects.

I firmly believe that a better understanding of the biology of light will reveal ways in which we can have our cake and eat it – use electronic light to support health, as well as to enrich work and play. There are already examples of this in action, but there is scope for so much more.

What have been the highlights of your lab’s work so far?

I was lucky enough to be able to contribute to some early steps in the discovery and description of the inner-retinal (melanopsin) photoreceptor that plays such an important role in our chronobiology.

If I had to pick one highlight from that work, I’d go for the Nature Neuroscience paper that established:

- a role for that receptor in driving the pupil light reflex (and thus demonstrating that it was responsible for detecting a particular visual quality – ambient light – rather than any single physiological endpoint);

- the receptor’s spectral sensitivity (it likes blue!);

- that it has lower sensitivity and temporal resolution than rods or cones. All before we knew exactly where or what the photoreceptor was.

The pupil study was also the start of another long-standing interest – how melanopsin may contribute to vision. This remains an area of active research for my group, and there is still much that we do not know.

However, we have been able to provide clear evidence that melanopsin both provides an origin for aspects of visual light adaptation (Current Biology 24(21):2481-90; PNAS 112(42) E5734-43; Neuron 93(2):299-307; PNAS 115(50):E11817-26), and can itself support a percept of brightness that is especially relevant for defining coarse patterns (PLoS Biology 8(12):e1000558; Current Biology 12:1134-41; Curr Biol. 27(11):1623-1632; Nat Commun. (2019) 10(1):2274).

Perhaps the most important question the world might ask of those of us studying light and clocks is how much light is enough/too much for circadian health. To answer, we first need a way of measuring light that predicts its ability to elicit circadian and associated light responses.

I am proud of the contribution my lab has made to providing such a measurement system. We introduced the concept of melanopic lux as a suitable metric (J Biol Rhythms 26(4):314-23). I subsequently established an expert working group with my co-chair Bud Brainard to agree consensus on light measurement in this field (TINS 37:1-9).

I have helped to see our work translated into a new SI-compliant international standard for light measurement, and more recently into the first quantitative guidance on light exposure (see PLoS Biol (2022) 20(3):e3001571).

What are the benefits of doing research at the University? What does Manchester offer that stands out from other universities?

The hardest thing I’d find to replicate elsewhere would be the people. We now have a collection of research groups with complementary interests in what we term TVB (Time, Vision, and Behaviour) led by Annette Allen, Mino Belle, Tim Brown, Nina Milosavljevic and Riccardo Storchi.

We share lab meetings and social events, and help each other out with infrastructure and experimental expertise. It’s just a lovely community, and a rich source of ideas and inspiration.

Moving just a little wider, the Centre for Biological Timing is of course a huge plus. So much exciting research on timing processes across traditional biological disciplines.

We are also lucky to have strong local communities in vision science (including the Manchester Vision Network) and neurophysiology. If I look at my publications, it’s striking how often people from those communities appear as co-authors, which tells its own story about how they have enriched my scientific life.

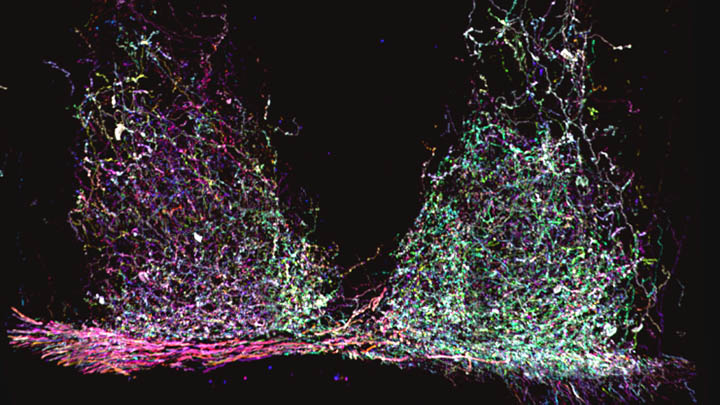

Having such strength over all my core scientific interests also means that we have access to lots of research expertise and infrastructure. Moreover, the Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health runs first-rate core facilities in histology, bioimaging, genomic technologies, and genome editing. It is unusual for our scientific ambition to be curtailed by lack of access to the tools we’d need to realise it.

What are the alumni from your lab doing now?

I’m very proud of my lab alumni. The vast majority of people leaving the lab have continued in science, either in industry or academia.

Some have stayed in Manchester, while others have moved on to work with collaborators around Europe and the world. Seven alumni have succeeded in obtaining academic positions at research universities in the UK or elsewhere, and we have one full Professor (Tim Brown) among that group.

Over the years, we’ve had a particular success in having postdocs in the group raise fellowship funds to take the critical step to independence. This has included awards from the BBSRC (David Philips), Wellcome Trust (Sir Henry Dale x2), the NC3Rs, and Fight for Sight.

Read more about Robert’s research in the Research Explorer.

0 Comments