Materials of Sleep: Water Lilies

This blog ‘mini-series’ explores the uses of specific materials for sleeping well. In this second post, Dr Leah Astbury investigates the connections between lust, lilies and sleep.

Figure 1 Woodcut from The Discontented Bride: Or, A brief Account of Will. the Baker, who Sow’d himself up in a Blanket every Night gowing to Bed, for fear of Enlarging his Family (London: 1685-1688).

Lustful thoughts and feelings were thought to be a significant impediment to getting a good night’s sleep in early modern England. A late-seventeenth-century ballad told of a baker who swaddled himself up every night tightly in blankets to block the amorous advances of his new Discontented Bride. For seven months she tossed and turned, lying ‘whining, perplexing and vexing’ next to him for want of sex. She attempted to hide the blanket only for him to find it and return to his peaceful slumber – ‘he little regarded her moan,/But snoring lay like a drowsie,/Wrapt up in his Blanket as tight as a pack,/And never consider’d what she did lack.’ At the end of the ballad she joyfully finds a lover and lets her husband have his ‘ease’ in ‘his Blanket’. Although expelling seed, for men and for women, was framed as an important part of excretion and health in early modern medical texts, being immoderately lustful could corrupt the body and the soul and ought to be tempered.

Printed guides to medicinal plants in the period often cited water lilies as being capable of quelling lust and facilitating restful sleep. Desire was thought to be chiefly caused by heat, and water lilies supposedly cooled the body. Similarly, sleep was thought only possible when the body was cool and settled. Sleepiness and not being too lustful were good bedfellows.

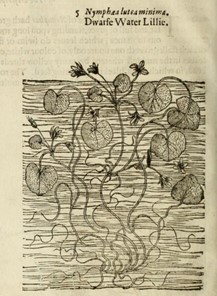

Figure 2 Woodcut of water lilies from John Gerard, Herball of Generall Historie of Plantes (London: 1633), p. 819

Thus, the popular herbalist John Gerard (c. 1545-1612) noted that the seeds and roots of water lilies could be ground up and put into drinks or mixed into meals to subdue ‘venerie or fleshy desire’. It would ‘drieth vp the seed of generation, and so causeth a man to be chaste, especially vsed in broth with flesh.’ The yellow parts of the flower were particularly useful in stopping the ‘ouerflowing of seed [semen] which commeth away by dreames or otherwise’, or nocturnal emissions. Likewise, William Cole’s 1657 Adam in Eden, or, Natures Paradise the History of Plants, Fruits, Herbs and Flowers, recommended boiling the seeds and roots of water lilies as of ‘wonderfull efficacy to coole, bind, and restrain’ and ‘exceeding good for those who shall endeavour to preserve themselves from Lechery and uncleanness.’ By consuming the roots or seeds or applying them to the genitals, the plant would not only stop nocturnal emissions but frequent use could ‘extinguisheth even the very Motions to venery’. Men and women could put lily pads on their back to cure other genital problems, or boil the leaves in ‘thick red wine’ and drink, Coles instructed.

Figure 3 Woodcut of water lilies in Gerard, Herbal (London: 1633), p. 820

Water lilies were not just used to quell lust but generally as a soporific and to quench fevers. According to early modern Herbals most apothecaries sold syrup of water lily flowers. This was useful in settling ‘the brains of Frantick persons’, curing distempers and facilitating ‘sweet and quiet sleep.’ Robert Turner in Botanologia (1687) similarly noted that both the syrup and distilled water of the plant would provoke sleep. The most famous guide to medical ingredients of the period, Pharmocopeia Londinensis (1661), similarly recommended water lilies for quelling fevers and helping people fall asleep.

The use of lilies to both quieten lasciviousness and cause sleep makes a lot of sense given the longstanding cultural link between the plant and innocence and virginity. In Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Elizabeth I is described as ‘A Virgin, A most vnspotted Lilly’ (v. iv.61). A sermon delivered by clergyman Peter Lily in 1619 hammered home the link between the flower and innocence ‘This Lilie pure delights in waters sure/[…] These Lilie leaues will make an humble minde.’ Being kept awake by lustful thoughts whilst your devotion slumbered was also a common analogy used by religious reformers: Robert Greene’s 1583 romance Mamilla warned young men how ‘lewde lust’ awakened would ‘their firme faith, brought a sleepe’. In a medicinal setting, perhaps water lilies’ association with sleep was strengthened by the way they appear to ‘sleep’ at night because their petals close.

Towards the end of the seventeenth century and early eighteenth century there was an intensified interest in ensuring young men did not ‘spend’ their seed outside of marriage. Masturbation was increasingly thought to be deleterious to health and fertility. But by the eighteenth century, lust and orgasm were thought to have a dangerously soporific quality. One 1717 anonymous correspondent who, having indulged in the sin of onanism described how he could not stir out of his ‘Bed for Two or three Days together’. The early eighteenth-century pamphlet Onania, or the Heinous Sin of Self-Pollution detailed how being lustful would do much more than disturb one’s sleep; it sent many to their graves. Water lilies were then, a crucial material agent in managing complex bodily needs, and in assuring a sound night’s sleep.

Towards the end of the seventeenth century and early eighteenth century there was an intensified interest in ensuring young men did not ‘spend’ their seed outside of marriage. Masturbation was increasingly thought to be deleterious to health and fertility. But by the eighteenth century, lust and orgasm were thought to have a dangerously soporific quality. One 1717 anonymous correspondent who, having indulged in the sin of onanism described how he could not stir out of his ‘Bed for Two or three Days together’. The early eighteenth-century pamphlet Onania, or the Heinous Sin of Self-Pollution detailed how being lustful would do much more than disturb one’s sleep; it sent many to their graves. Water lilies were then, a crucial material agent in managing complex bodily needs, and in assuring a sound night’s sleep.

For more theory about libido in early modern England and heat see, Jennifer Evans, Aphrodisiacs, Fertility and Medicine in Early Modern England (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2014).

0 Comments