Materials of Sleep: Tobacco

This blog ‘mini-series’ explores the uses of specific materials for sleeping well. In this third post, Lucy Elliott investigates the relationship between tobacco and sleep.

The tobacco plant, from Nicholas Monardes, Joyfull newes out of the new-found worlde (London: 1577)

Publishing his history of the colonisation of the Americas in the mid-sixteenth century, the Spanish colonialist and historian Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo described a ‘bad habit’ among the indigenous populations there. An unusual new herb, considered ‘very precious’ to the indigenous peoples that they encountered, enjoyed frequent use by them to ‘alter their senses’ and bring about a state of drowsiness. So potent was this herb that it could trigger sudden physical collapse. ‘When the cacique or principal man falls down to the ground’, Oviedo wrote, women would come to ‘lay him in his bed or hammock, if he had told them to do so before he fell; if he hadn’t said so nor requested this beforehand, he does not want anything but for them to leave him on the ground until the intoxication and sleepiness passes.’ The herb in question was tobacco, and following its introduction to Europeans, they too would come to associate it with sleep.

Modern findings have shed further light on the relationship between sleep and tobacco: a 2021 medical analysis of tobacco-induced sleep disturbances found that chronic tobacco users had an impaired sleep quality when compared to non-smoking adults. Today, we know that exposure to tobacco smoke is accompanied by a range of other serious health risks, with around 78,000 annual deaths in the UK attributable to smoking. While we might associate scientific discourse around tobacco’s effects with the anti-smoking campaigns of the twentieth century, early modern Europeans encountering tobacco for the first time were keen to understand how tobacco consumption might impact and change their bodies.

Following Columbus’ first voyage in 1492, European explorers who voyaged to the Americas encountered and recorded a range of plants and animals previously unheard of in the ‘Old World’ of Europe. Tobacco, sometimes referred to as petum or nicotiana, was one of these plants, and travel accounts suggest that it was smoked widely by the indigenous peoples that the Europeans encountered. Two other names it would come to be known by, herba medicea – or ‘medical herb’ – and herba panacea relay the way that tobacco was initially lauded as a ‘cure-all’ for a wide range of ailments in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Tobacco’s ability to influence sleep was consistently referred to as one of its more prominent qualities in descriptions of its medical uses. The seventeenth century medical writer Edmund Gardener described consumption of the herb as being particularly good for ‘sleepie’ persons, who upon taking it could expect to have ‘all drowsinesse banished and chased out of their minds’.

A sleeping woman being provoked by two men with tobacco pipes. Mezzotint by W. Baillie after G. Dou (1774)

Wellcome Collection

The relationship between tobacco and sleep was, nonetheless, complex. Tobacco might provoke sleep, but it could also compel the body to be more alert and awake. The sixteenth-century Dutch physician Giles Everard noted that tobacco consumption could ‘make one sleep, who wants rest’ and yet it could also keep ‘a Scholar waking in his study, and a soldier upon his guard’. Early modern writers speculated about the causes of tobacco’s varied effect upon a body’s alertness, with some pointing to the amount consumed, the weariness of the person consuming it, and the method of ingestion. The versatility of tobacco was a source of some discussion, with Everard writing that while ‘the upper Scout of Amsterdam, as some report, chews it against all diseases’, the Irish ‘Snuff tobacco to purge their brains’, and ‘the Indians swallow down the smoke against weariness, till they fall into an Extasie’, the ‘ordinary way to suck it from a pipe’ was the best in clearing distillations from the head.

Examining exactly how tobacco was presumed to work in the body sheds some light on its unique connection to sleep. The herbalist John Gerard (1545-1612) remarked in The herball or Generall Historie of plantes that the ‘stupifying or benumming qualitie’ possessed by tobacco was ‘not hard to be perceived’, ‘for upon the taking of the fume at the mouth there followeth an infirmitie like unto drunkennesse, and many times sleepe’. Gerard was one of many who assigned the properties ‘hot’ and ‘dry’ to tobacco, two descriptors that outlined its place in the system of Galenic medicine, which classified herbs by the qualities of heat, cold, dryness, and moisture. As Gerard was certain of tobacco’s heat, owing to the ‘biting qualitie of the leaves’ and its ability to ‘draw out filth and corrupted matter, which a cold Simple would never do’, its benumbing effect was one that compelled him to question its workings. Gerard notes with curiosity that while ‘Galen and all the old Physitions doe hold opinion’ that a benumbing quality arises only from extreme cold, yet ‘Tabaco is not cold and benumming; but hot and benumming […] not so much by reason of his temperature, as through the propertie of his substance’. Tobacco’s ability to benumb the body and provoke sleep was then a point of particular interest, as its innate heat seemingly contradicted prior understandings that a benumbing effect was only the nature of things that were cold.

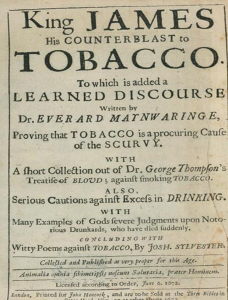

King James I’s A counterblaste to tobacco (1604)

Tobacco’s soporific effects did not mean that it was universally accepted as beneficial by writers of the day. King James I was one of tobacco’s most vocal opponents. In his Counterblaste to Tobacco (1604) he mocked the seemingly contradictory nature of tobacco as an agent of sleep, questioning how it ‘being taken when they goe to bed, it makes one sleepe soundly, and yet being taken when a man is sleepie and drowsie, it will, as they say, awake his braine, and quicken his vnderstanding’. Many of his fellow critics of tobacco consumption, however, did not doubt the herb’s connection to sleep and refreshment – instead, they questioned the legitimacy of its workings. ‘That [tobacco] hath a property to depress and clog the Spirits, is apparent by its narcotick vertue, causing a dulness, heaviness, lassitude, and disposing to sleep after the use of it,’ noted an anti-tobacco pamphlet published in 1676. Yet this use ‘alienates the Spirits’ and was ‘discord with our nature’, potentially inviting diseases such as scurvy into the body. Similarly, although some might take tobacco for ‘refreshment after labour’ and ‘being tired with business, study, and musing’, the same author argued that it might make one ‘seemingly delighted and refreshed for a short time, yet afterwards the Spirits are lassated and tired […] not truly refreshed’. While the soporific and stimulating effects of caffeine were reinforced by these critics, they argued that using tobacco for these purposes was nevertheless detrimental to the body.

The debate about how and why tobacco consumption triggered varied states of sleepiness and alertness continued into the eighteenth century but many continued to value the herb as an effective soporific. The anonymous poem Nicotianæ encomium; or, the golden leaf tabacco (1700) praised tobacco thus: ‘thou Sleep procures, and rock’st our Cradle-Beds’. Sleep’s relationship with tobacco thus has a long and complicated history.

0 Comments