Materials of Sleep: Flax and Hemp

In this latest instalment of our mini-series ‘Materials of Sleep’, Professor Sasha Handley explores the importance of hemp and flax in the production of bedding materials in early modern England and early America.

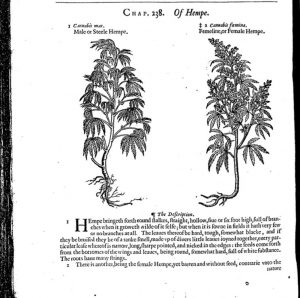

Figure 1: John Gerard, The herball or Generall historie of plantes (London, 1633)

Hemp (Cannabis) and flax (Linus usitatissimum) were two staples of early modern healthcare and textile manufacture. Medicinally, hemp and flax had a wide variety of physical applications when ingested. Amongst their benefits, proposed William Langham in his popular herbal, The garden of health (1597) was the ability to cool fevers and reduce inflammation. These advantages, alongside the widespread use of both plants in the manufacture of bedding textiles, made them a staple of the early modern English household, and of agriculture. Though distinct in their appearance, composition and cultivation needs, the two plants were frequently drawn together in discussions of linen manufacture.

Agricultural writers gave advice about how and where to sow hemp and flax, that reveals a deep well of localised environmental knowledge that connected the soil to recumbent sleeping bodies. The anonymous treatise England’s Improvement (1691) for example, began its directions about cultivating hemp and flax by focusing on the most beneficial soil types in which to plant them. William Camden was convinced that the soil of Bridport in Dorset produced the best hemp, whilst others judged the most fertile soil to be ‘sandy ground mixed with Earth’, which was very often found in ‘old Meadows grown over with moss, old Stack-yards, and places kept in the Winter for the Lair of Sheep or Cattel’. Different soil types shaped the colour of flax plants whose properties ‘participated’ in the ‘nature of the Soil’. Linens were valued within a visual hierarchy of colour, in which the whitest bleached linens were increasingly aligned with cleanliness, healthfulness and cost.

Figure 2: Flax in bloom and tied in bundles to dry, in The Huntington’s Herb Garden

For many, the ways in which flax and hemp were understood to ‘participate’ in ecologies of cultivation was a healthcare concern, but also a food security concern. Hemp, in particular, was believed to pollute certain waterways and their aquatic life. In his influential work The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) Robert Burton reflected on the significance of hemp’s cultivation process, in which the plant’s fibres were steeped in water to soften them and make them easier to break. Burton stated that ‘Standing Waters, thicke and ill coloured, such as come forth of Pooles and Motes, where hemp hath been steeped, or slimy fishes live are most unwholesome, putrified and full of mites, creepers, slimy, muddy, uncleane, corrupt, impure by reason of the Sonnes heat: and still they cause foule distemperatures in the body and minde of man, and are unfit to make drinke of, or to dresse meat with, or to bee used about men inwardly or outwardly’. His concerns about the potentially toxic effects of standing waters were partly reflected in agricultural treatises. Many of them identified wide running streams as the optimal waterways to hydrate hemp and flax fibres and to encourage their leaves to fall off but even those streams that ran ‘broad’ and ‘swift’ still had to be free of fish, to which hemp was deemed ‘offensive’. Bodily health, and the healthfulness of bedding materials, were then significant considerations in the châine operatoire of linen production, in which concerns about sleeping well were partly influenced by concerns about food security. Amercements (fines) issued by manorial courts to punish people that ‘dived’ hemp in inappropriate places suggests that these two commonplace concerns were often in conflict.

Knowing how to manufacture good-quality linens from seed was considered a staple part of a good housewife’s armoury, although opportunities to engage in this agricultural practice varied widely. Most agricultural treatises of this period were authored by men, yet the directions they gave for cultivating hemp and seed, and transforming their fibres into linens, were likely common knowledge amongst labouring women whose job it was to feed and clothe the household, tend to their healthcare needs, and manage the family purse-strings. It is impossible to accurately quantify the extent, or regional practice, of hemp and flax cultivation by individual women. This practice was nonetheless likely to be widespread given the costs of purchasing ready-made linen, and given the consistent preference for linen bedsheets throughout this period, in spite of the growing availability and affordability of cottons. Gervase Markham identified a specific housewifely vocabulary for parts of the cultivation process, which suggests that his own knowledge was at least partly based on observation of their practices. Aside from embodying women’s essential role in safeguarding the sleep fortunes of their loved ones, hemp and flax manufacture probably had a significant and differential impact on their sleep routines. Once the seeds of both plants had been sown in the ground, usually between February and April, they had to be carefully tended each morning, ideally ‘an houre or two before Sun rise’ to prevent birds and ‘other vermine’ from eating them. This meant heading into the fields between 5 and 5.30am on these wintry mornings.

Knowing how to manufacture good-quality linens from seed was considered a staple part of a good housewife’s armoury, although opportunities to engage in this agricultural practice varied widely. Most agricultural treatises of this period were authored by men, yet the directions they gave for cultivating hemp and seed, and transforming their fibres into linens, were likely common knowledge amongst labouring women whose job it was to feed and clothe the household, tend to their healthcare needs, and manage the family purse-strings. It is impossible to accurately quantify the extent, or regional practice, of hemp and flax cultivation by individual women. This practice was nonetheless likely to be widespread given the costs of purchasing ready-made linen, and given the consistent preference for linen bedsheets throughout this period, in spite of the growing availability and affordability of cottons. Gervase Markham identified a specific housewifely vocabulary for parts of the cultivation process, which suggests that his own knowledge was at least partly based on observation of their practices. Aside from embodying women’s essential role in safeguarding the sleep fortunes of their loved ones, hemp and flax manufacture probably had a significant and differential impact on their sleep routines. Once the seeds of both plants had been sown in the ground, usually between February and April, they had to be carefully tended each morning, ideally ‘an houre or two before Sun rise’ to prevent birds and ‘other vermine’ from eating them. This meant heading into the fields between 5 and 5.30am on these wintry mornings.

Hemp and flax cultivation were long-established agricultural practices in early modern England, both for self-sufficiency and for commercial profit. They were also practices that English travellers and colonists sought to replicate in early America and that guided their recommendations about viable, and profitable, settlement sites. John Brereton’s explorations of the islands off the coast of Newfoundland led him to observe how similar the soil was to England’s ‘hempelands’ and surmised that it was ‘apt’ for growing that plant in abundance. The soils of North Virginia offered similar promise, as did the watery banks of the Saint Lawrence river to the west of Newfoundland, on which hemp had already taken root. These travel accounts generally framed the prospects to cultivate flax and hemp as commercial opportunities (whilst noting it would be women’s work to undertake the cultivation). They nonetheless identify these plants as staples for the day-to-day subsistence of a sustainable, comfortable and healthy colony.

Further Reading/Viewing:

1. For a historical reconstruction of flax-linen manufacture see Usha Lee McFarling, ‘A Fascination with Flax’, The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, 9 December 2020.

2. Styles, John, ‘Transformations in Textiles, 1500-1760’ in Refashioning the Renaissance: Everyday dress and the reconstruction of early modern material culture, 1550-1650 edited by Paula Hohti (forthcoming, 2023)

3. Clarke, R.C., Merlin, M.D. Cannabis: Evolution and Ethnobotany (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

4. Allegret, S. ‘The history of hemp’ in Hemp: Industrial Production and Uses edited by P. Bouloc, S. Allegret, and S. Arnaud (CAB International: Bar sur Aube, France, 2013); pp. 4–25.

0 Comments