New Book on Aby Warburg, Fritz Saxl and Gertrud Bing: An Interview with Dorothea McEwan

Dorothea McEwan was appointed the first archivist of The Warburg Institute Archive, London, in 1993. Her research interests include Aby Warburg, Fritz Saxl and Ethiopian illuminated manuscripts and Ethiopian history. In 2008 she was awarded the Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art, in 2017 she was elected Associate Fellow of the Ethiopian Academy of Sciences and in 2021 she was awarded the Grand Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria. The publication of her new book, Studies on Aby Warburg, Fritz Saxl and Gertrud Bing (Routledge, 2023), is an opportunity to reflect on the contemporary significance of the work of Aby Warburg and his early collaborators.

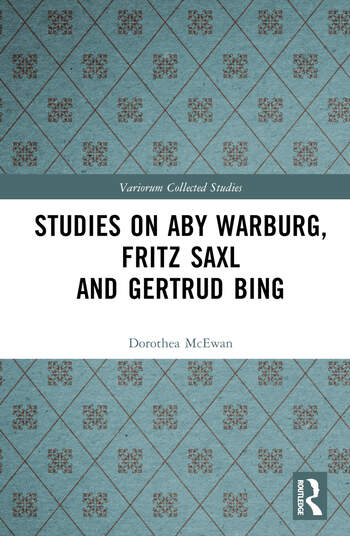

Stefan Hanß: Dorothea, warm congratulations on the publication of your most recent book! Studies on Aby Warburg, Fritz Saxl and Gertrud Bing (Routledge, 2023) is a collection of 17 articles that have previously been published in German, Italian and French, now translated into English for the first time. Can you give the readers a flavour of the topics covered?

Dorothea McEwan: Thank you, Stefan, for your kind congratulations. The need to translate my non-English articles into English became ever more urgent, as the reading competence of scholars, being used to read articles in a variety of European languages, fell victim to many contemporary processes and educational bottlenecks. From the beginning of my work as Archivist it became requisite to abstract the large corpus of Warburg correspondence, 37, 000 letters and postcards in English and not in their original seven languages used by Aby Warburg. The translation of seventeen articles which I wrote in German, Italian and French are therefore an aid to assessing Warburg’s, Saxl’s and Bing’s intellectual pursuits and activities for the next generations of Warburg scholars.

Using the Archive in The Warburg Institute as source I proceeded to publish research topics which to my mind had not been studied conclusively or so far without recourse to important archival sources. In Part I of my book Studies on Aby Warburg, Fritz Saxl and Gertrud Bing, I concentrated on a selection of Warburg’s main research topics, the Palazzo Schifanoia with its wall paintings of the decans and Warburg’s coherent interpretation in 1912 just as much as an article on a small linocut, Aby Warburg’s artistic commission called Idea Vincit, the victory of the idea, to celebrate the Peace Nobel Prize for Aristide Briand and Joseph Chamberlain, both the Foreign Ministers of their countries, and Gustav Stresemann, the German Foreign Minister on the occasion of Stresemann’s visit of the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg in 1926. Whilst some topics had been discussed earlier on, I concentrate on working on the genesis of research topics, such as Warburg’s initiative of publishing two issues of the journal called Rivista Illustrata in 1914 and 1915, on the origin of Warburg’s Serpent Ritual lecture in 1923, and the correspondence with the Moravian scholar, František Pospíšil, who travelled through Europe with his film camera to research sword dances in the 1920s.

Parts 2 and 3 present chapters showing Warburg’s collaboration with scholars, his relative James Loeb, the founder of Loeb’s Classical Library, Warburg’s rather cool relationship with members of the Vienna School of Art History, a chapter on Josef Strzygowski and Warburg’s view of him. The topics of Gnosticism just as much as Mithraism were mainly Saxl’s research agenda but both these topics show the interplay and collaboration between Saxl and Warburg, whilst a chapter on ‘Caricature as war effort’ presents Warburg in the guise of commentator of political events during World War I in text and images.

Part 4 investigates Judaica topics, the trip of Warburg’s niece Gisela, 17 years of age, to Palestine and her impressions as well as the work and conversion of A. A. Barb, an Austrian scholar, who had been forced to give up his post as first director of the Museum in Eisenstadt, Austria, was able to flee to Great Britain with Bing’s help and was after World War II offered the post of librarian in the Warburg Institute.

The final three chapters deal with Warburg’s interest in the figure of Struwwelpeter, the painted triptych of Mary Warburg and a very personal interview with a French colleague.

SH: While most researchers focus on Aby Warburg exclusively, your approach has always been more holistic. You have previously published a biography of Fritz Saxl—available open access—that I like to think of as an important accompanying reading to Ernst H. Gombrich’s famous intellectual biography of Aby Warburg. After all, art historian and head librarian Fritz Saxl was to become Warburg’s successor as director of the library and later The Warburg Institute. Also Gertrud Bing’s contributions are often overshadowed by research on Warburg. Based on you years-long work as The Warburg Institute’s first archivist, what would you say about the importance of Bing and Saxl in shaping Warburg’s thought and legacy?

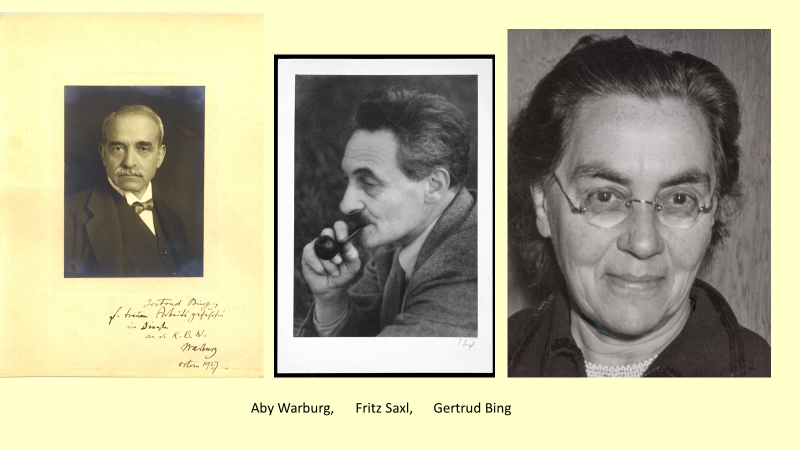

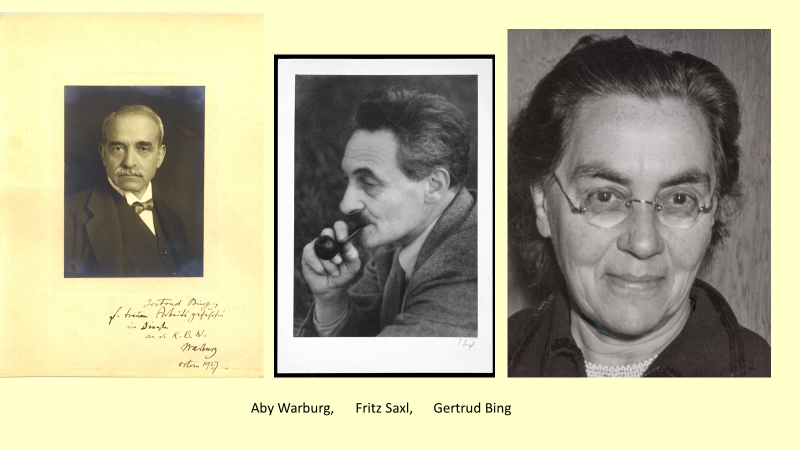

DMcE: Saxl, the art historian, and Bing, the philosopher, worked closely with Warburg in the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg in Hamburg in the 1920s. It was Saxl, who as a young man, was clear about the function of the library of a private scholar: he suggested to Warburg to open his private library to academic work within the newly founded University of Hamburg and the triumvirate of three scholars, Warburg, Saxl and Bing, was able to jointly create a seat of learning, discussion, scholarship and investigation into the cultural roots of art history, literature, religion and other intellectual pursuits. Both Saxl and Bing were trusted by Warburg, both devoted their whole lives to the particular research agenda, for which Saxl coined the phrase Die Wanderstraßen der Kultur or ‘the pathways of culture’.

Photographs in the Portrait Collection in the Warburg Institute Archive.

DMcE: There was cross-fertilisation, there was scope for following their own research work, there was trust and unity in the goal, a new goal beyond the narrow confines of academic subjects and institutes. Through the help of Saxl and Bing the entire library was shipped to London in 1933, and the work resumed in London, now called The Warburg Institute, in the pursuit not of one particular academic subject, but of the multifaceted collaborative work which so distinguished the work in Hamburg. It became an international centre in the humanities focusing on the ‘afterlife’ of antiquity. Saxl became its first professor in London and Bing followed in the 1950s.

Dr. D. McEwan, in front of Warburg’s Zettelkästen, Photograph of Ian B. Jones.

SH: The book reflects on your decades-long research on the subject, and also your own biography is closely linked to The Warburg Institute. How did you discover the works of Saxl and Bing the first time and what do you consider Aby Warburg’s legacy for researchers today?

DMcE: As a historian working first in the Department of Manuscripts in the British Library and then in Goldsmiths’ College I knew about the excellent reputation of the Warburg Institute. Through friends I was introduced to Professor Sir Ernst Gombrich, formerly director of The Warburg Institute, who was on the look out for a Research Assistant. My ten years in this role not only acquainted me with the work of Warburg, Saxl, a fellow-Viennese, and Bing and Gombrich’s esteem of their research agenda, but also with their ways of dealing with research questions. I learnt a great deal as Gombrich’s Research Assistant, I was, as a matter of course, impressed by the vast knowledge of Professor Gombrich, but also of his sense of humour, expressed in two languages, first in English when telling me a joke and then, when it came to the punchline, in German. We both laughed and enjoyed the much richer meaning of the German denouement. I remember fondly days spent in his house in Golders Green, his wife, Lady Gombrich, showing me their Christmas tree decked out with little toys of their son Richard, or listening to both playing a piece of Austrian classical music on the piano and cello. When the postman came and everyday delivered a stack of mail, there undoubtely was at least one book among the mail with a preface by the author thanking Professor Gombrich for his wise counsel, which Lady Gombrich commented by starting the Lord’s Prayer thus: ‘… give us today our daily book…’. When the post of Archivist was established in The Warburg Institute, Gombrich encouraged me to put in for it. And the rest is history, as the saying goes.

SH: Please let me ask a final question about the future. Most readers of this interview will have an interest in the history of the body, emotions and material culture studies. What insights can they gain from your new book, and the works of Warburg, Saxl and Bing more generally?

DMcE: I thank you for this question, as it was an important research topic to Warburg, Saxl and Bing. Warburg famously discussed the ‘accessories in motion’ when he saw the Ninfa, the eternal woman in Italian Renaissance paintings, walking with light steps in the cityscape or landscape of Italy, her skirts swinging, her veil and hair as if in motion. The painting expresses motions and emotions, famously in Warburg’s PhD which he devoted to the investigation of the Botticelli’s paintings The Birth of Venus and Primavera. His most extensive research is the famous Mnemosyne Atlas with its combinatory experiments in the symbolism of images.

Saxl researched, among other topics, late paganism and early Christianity and with it the change in symbols or the continued afterlife of symbols, or the images of the so-called ‘planet children’ in Renaissance art, the planet children surrounding the planets, or Mithraic altar stones with their 12 rectangles of decorations.

Bing’s life was defined by her work as editor of Warburg’s collected writings, Fritz Saxl’s lectures, and the publications of the Warburg Institute. She was instrumental in helping a large number of German, Austrian and Czech scholars who were persecuted in the 1930s in Europe and managed to come to the UK and with Bing’s help find work in academic institutions.

My book, therefore, brought in the harvest of my years as archivist in The Warburg Institute. I remember fondly the many discussions with archive users, as well as the many discussions on how to shape the papers collected by Warburg into a collection available and useable easily to scholars in London as well as abroad. Digital technology helped in this task, the great number of books and articles written with the help of archival sources give testimony that it was the right way to pursue. And having been able to assist in this way is a great joy to me.

SH: Thank you so much, Dorothea. It was a huge joy to talk to you.

The book Dorothea McEwan (2203), Studies on Aby Warburg, Fritz Saxl and Gertrud Bing. London: Taylor & Francis. Imprint: Routledge is available in the following formats:

ISBN: 978-0-367-76941-3 (hbk),

ISBN: 978-0-367-76944-4 (pbk),

ISBN: 978-1-003-16902-4 (ebk).

0 Comments