Women, Labour and Embodiment in the Material Renaissance: Interview with Laura Gowing, Stefan Hanß and Beverly Lemire

This interview discusses the labour and skills of early modern working women. Laura Gowing and Beverly Lemire have asked Stefan Hanß to further elaborate on

‘Gendering the Material Renaissance: Women, Industriousness and the Female Body at the Court of Württemberg’—an open access journal article recently published in German History (OUP):

https://academic.oup.com/gh/advance-article/doi/10.1093/gerhis/ghad031/7199842

Laura Gowing is Professor of Early Modern History at King’s College London and Fellow of the British Academy. Her book Common Bodies: Women, Touch and Power in Seventeenth-Century England (Yale, 2003) was awarded the 2004 Joan Kelly Memorial Prize by the American Historical Association. Her most recent Ingenious Trade: Women and Work in Seventeenth-Century London (CUP, 2022) uncovers the history of young women who came to London in the late seventeenth century to earn their own living, most often with the needle, and the mistresses who set up shops and supervised their apprenticeships. The book recovers the significance of apprenticeship in the lives of girls and women, and puts women’s work at the heart of the revolution in worldly goods. For Ingenious Trade, Laura Gowing was awarded the Social History Society’s Book Prize.

Laura Gowing is Professor of Early Modern History at King’s College London and Fellow of the British Academy. Her book Common Bodies: Women, Touch and Power in Seventeenth-Century England (Yale, 2003) was awarded the 2004 Joan Kelly Memorial Prize by the American Historical Association. Her most recent Ingenious Trade: Women and Work in Seventeenth-Century London (CUP, 2022) uncovers the history of young women who came to London in the late seventeenth century to earn their own living, most often with the needle, and the mistresses who set up shops and supervised their apprenticeships. The book recovers the significance of apprenticeship in the lives of girls and women, and puts women’s work at the heart of the revolution in worldly goods. For Ingenious Trade, Laura Gowing was awarded the Social History Society’s Book Prize.

Beverly Lemire is Professor and Henry Marshall Tory Chair in the Department of History and Classics, University of Alberta. She examines intersecting areas of material culture, gender, race and fashion from circa 1600 to 1900 in British, imperial and comparative projects. Her monograph Global Trade and the Transformation of Consumer Cultures: The Material World Remade, c. 1500–1820 (CUP, 2018) is a widely celebrated, field-shaping intervention that brings a novel global framework to the study of early modern material cultures, spearheading new concepts like ‘material cosmopolitanism’ and ‘cosmopolitan consumption’, as well as ‘industriousness’. Object Lives and Global Histories of Northern North America: Material Culture in Motion, c. 1780–1980 (MQUP, 2021), edited by Beverly Lemire, Laura Peers and Anne Whitelaw, won the Horowitz Book Prize for the best book on the decorative arts, design history or material culture of the Americas.

Beverly Lemire is Professor and Henry Marshall Tory Chair in the Department of History and Classics, University of Alberta. She examines intersecting areas of material culture, gender, race and fashion from circa 1600 to 1900 in British, imperial and comparative projects. Her monograph Global Trade and the Transformation of Consumer Cultures: The Material World Remade, c. 1500–1820 (CUP, 2018) is a widely celebrated, field-shaping intervention that brings a novel global framework to the study of early modern material cultures, spearheading new concepts like ‘material cosmopolitanism’ and ‘cosmopolitan consumption’, as well as ‘industriousness’. Object Lives and Global Histories of Northern North America: Material Culture in Motion, c. 1780–1980 (MQUP, 2021), edited by Beverly Lemire, Laura Peers and Anne Whitelaw, won the Horowitz Book Prize for the best book on the decorative arts, design history or material culture of the Americas.

Stefan Hanß is Professor of Early Modern History at The University of Manchester and incoming Deputy Director and Scientific Lead of The John Rylands Research Institute. He is the winner of a British Academy Rising Star Engagement Award (2019) and a Philip Leverhulme Prize in History (2020). Hanß works on global material culture and cultural encounters. His most recent monograph and edited volume are Narrating the Dragoman’s Self in the Veneto-Ottoman Balkans, c.1550–1650 (Routledge, 2023) and, co-edited with Beatriz Marín-Aguilera, In-Between Textiles, 1400–1800: Weaving Subjectivities and Encounters (AUP, 2023). ‘Gendering the Material Renaissance: Women, Industriousness and the Female Body at the Court of Württemberg’ has been just published open access with German History.

Stefan Hanß is Professor of Early Modern History at The University of Manchester and incoming Deputy Director and Scientific Lead of The John Rylands Research Institute. He is the winner of a British Academy Rising Star Engagement Award (2019) and a Philip Leverhulme Prize in History (2020). Hanß works on global material culture and cultural encounters. His most recent monograph and edited volume are Narrating the Dragoman’s Self in the Veneto-Ottoman Balkans, c.1550–1650 (Routledge, 2023) and, co-edited with Beatriz Marín-Aguilera, In-Between Textiles, 1400–1800: Weaving Subjectivities and Encounters (AUP, 2023). ‘Gendering the Material Renaissance: Women, Industriousness and the Female Body at the Court of Württemberg’ has been just published open access with German History.

Beverly Lemire: Ground-breaking histories have shown the way that seemingly reticent sources can be revealing when care and a critical perspective is applied. The 9,000 receipts you used for court purchases are clearly such a collection. What were your thought processes as you approached and assessed this large mass, especially given that the women artisans were named—as were the things they were selling?

Stefan Hanß: The discovery of this source collection caused sheer excitement! They are so rich in detail, touching upon almost every aspect of material culture at this early modern court, and their serial nature allows for deep comparisons and wider reflections.

I started working on this collection in 2016 in my role as a Research Associate in Early Modern European Object History at The Faculty of History, University of Cambridge, and as part of the SNSF-funded project Materialized Identities. By then, these sources had been only touched upon in research from the early 1970s. In the meantime, also featherworkers featuring into the Stuttgart receipts have been discussed by Ulinka Rublack in the SNSF-project’s edited volume, but the receipts cover so much more. They are a treasure chest for research on making and makers; materials, embodied practices, and material transformation; courtly life in general and consumers as well as consumption in particular. I transcribed these sources systematically and used them widely for teaching.

“I am so grateful for exciting discussions with undergraduate students at The University of Manchester over the years.” (Stefan Hanß)

I am now in the process of editing these sources, making the transcriptions available to the wider research community.

For the history of early modern women’s labour in particular, this source collection is quite a windfall. The receipts detail makers, their names, professions and at times even the locations of their workshops. The sources also discuss artefacts, materials and practices of making, as well as commissioners, purchasers and prices. The receipts also point to networks, dependencies and communities. Of course, the receipts are anything but complete and they have their very own limitations. However, this plethora of information is in harsh contrast to the often hidden, or rather silencing, nature of sources on early modern women’s work. Maria Ågren rightly stresses that women’s labour ‘has left few traces in the historical sources, and when mentioned at all, women’s work tends to turn up somewhat randomly.’ The Stuttgart receipts are thus rather unique for their level of detail as well as their serial nature. They show women’s active role in shaping early modern material culture from different social angles, as makers and commissioners. This is particularly important since production and consumption were overlapping fields in the Renaissance, and thus not as separated as we might think of them today.

Still, serial records can be challenging to work with. I have been trained by microhistorians from early on in my career, and I am indebted to the work of historians that embrace deep contextualisation and the complexity of the past whilst reflecting on the nature, limitations and problems of historical knowledge and the writing of history itself. It would have been easy to bury individual stories with prices, numbers and charts but this would have been yet another silencing act. I tried to translate such archival information into a narrative that addresses the social world of women’s lived experiences. Making their names visible, making their own making visible as such, and lending their experiences voice was key to me.

Material analysis of artefacts from the early modern court of Württemberg. © Katharina Küster-Heise and Stefan Hanß.

Laura Gowing: Reconstructing the world of women’s artisanal creation, this piece stitches together so many topics: artisanship, female industriousness, embodied skills and the rich material culture of the Renaissance court. Indeed,

“one of the most engaging aspects of the piece (alongside its glorious detail of taffeta, velvet, hemming and twisting) is the number of different approaches to material culture and its documentation that you draw on.” (Laura Gowing)

Can you say something about the kinds of methodology historians need to recover women’s work and the gendered world of fashion consumption and making?

Stefan Hanß: There is so much to say about this. Since women’s work is often hidden in the archival documentation,

“historians have a moral obligation to develop an open-minded, multifaceted and inclusive set of methods.” (Stefan Hanß)

We should carefully read our textual sources and situate them within different genres. Contextualisation and deep archival research are key, as are considerations regarding the politics of authorship and visibility, for instance, the often gendered nature of the early modern print market, or what it meant for early modern men like Ramazzini or Siebmacher to write about working women’s bodies as fragile or women’s material creativity as resulting from a male creator’s insemination.

Historians must also embrace working with material evidence. The study of objects can reveal stunning insights into the worlds of early modern women. If we take the time to look at such objects properly, repeatedly, carefully and with care, they can fundamentally enrich the stories that we uncover about the past. We are so fortunate to have such a rich collection of material culture from the Stuttgart court in the Landesmuseum Württemberg, and I am extremely grateful for inspiring conversations with Katharina Küster-Heise and Bettina Beisenkötter. Conversations with curators and conservators should be at the forefront of methodological innovation in material culture studies and are pivotal in uncovering the hidden histories of working women. I also studied such objects with the digital microscope to focus on practices of making and to reconsider women’s work and skills as embodied and cognitive achievements. For instance, the microscope helped me reconsidering textiles as made things: embroidering and lace-working women required manual dexterity to have become embodied rhythmicity; minute eyesight; time, as well as physical, emotional and economic investments; the intricate use of tools; technical sophistication; and the cognitive and creative engagement with the translation of materials into designs. It is such material analysis that helps us reconsidering the significance of apprenticeship that is at the heart of early modern women’s work—as your research, Laura, has shown so impressively.

I also learned a lot from interdisciplinary research, especially anthropologists’ studies of making and the body, as well as theoretical material culture studies in archaeology. Moreover, we have such a rich pool of research to draw upon as historians! It was so refreshing to re-read some of the most seminal studies of the history of the body, material culture studies, gender studies and the history of labour, consumption and fashion—and to do so not in isolation but in conversation with each other. Too often we tend to see such strands of research in isolation but working, matter and bodies are entangled and so should be our readings. I also learned so much from re-reading some of the most classical studies of proto-industrialization and early modern subsistence economy and labour, reading such literature now with the eyes of a historian committed to material culture studies.

“Embodied making is a concept with considerable potential for comparative and collaborative study, including with close study of material evidence. It is rich.” (Beverly Lemire)

Beverly Lemire: Embodied making invites comparisons and collaborations, either across space or sector. Your emphasis on the physicality of production, including its rhythm, brings us into conversation with ethnologists and others and I immediately thought of the backstrap loom, where the weaver is literally part of the apparatus. Your discussion shows that to be true of other tool/hand interactions. Kate Smith brought this to the fore as well, examining the importance of “moving hands” in the making of ceramics in Wedgewood workshops. When we see bodies as gendered instruments, we then get closer to historic and cultural understandings and there is scope to do more. Of course, women’s interactions with making, repairing and washing also encompassed the “pains” of their labour.

How might your research further inform scholars including those working in other contexts?

Stefan Hanß: Embodiment is key in making, and the material Renaissance furnished a particular fascination for the embodied epistemologies of making, as Pamela Smith’s ground-breaking work has shown. Material transformations therefore were key to the articulation of broader cultural concepts of the time.

I am so pleased and grateful for your comment, Beverly. I agree that a focus on embodiment urges us to think more carefully about historically and culturally specific bodies. It calls for a historicization of making, matter and bodies alike and, most crucially, together as fluid, entangled, convergent and jointly emerging, experiential categories. This invites us to consider making as cognitive achievements, and I found the notion of the ‘extended mind’ particularly useful to reflect on the use of tools and early modern understandings of making and ingenuity—of course under the precondition that the mind and the body have never been separated as such. A focus on embodiment also urges us to consider experiences as tied to specific, individual bodies. This links material practices with notions of the self. In that regard, Denise Arnold’s ‘Making Textiles into Persons’ article in the Journal of Material Culture was a particularly inspirational reading that made me write about “period hands” elsewhere, in an article on featherwork, textiles and knots in the early modern Spanish world. A novel focus on the bodies of specific makers however also calls attention to the gendered experiences of making. The wider literature on early modern material culture has often discussed embodied making in reference to figures like Albrecht Dürer or Wenzel Jamnitzer, but I hardly find them representative for the experiences of the women (and often also the men) mentioned in the Stuttgart receipts. Finally, a focus on embodiment also provokes reflections on the physical hardships of making and thus denies any romanticization.

A study of embodiment and extended bodies allows us to foreground training and skills; creativity and industriousness; labour and hardships; as well as changing material practices, communities and values. It invites new collaborations with makers as I have done, for example, in research on featherworkers, and the focus on early modern women’s bodies also opens a conversation between often isolated historiographies, namely research on material culture, labour, consumption and gender or, as I think future studies will show, the history of emotions, food, health and medicine.

Joint bodily routines and strategies of sewing, embroidering and weaving women. J. Siebmacher, Schön Neues Modelbuch von allerleÿ lustigen Mödeln naczunehen, zuwürcken un[d] zusticke[n] … (Nuremberg, 1597), title page. ©Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Munich, Rar. 499f, urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00026001-0.

Beverly Lemire: I was struck by the attention to payment and the considerable amounts that women artisans earned in their sale of luxuries to the court. Payment clearly mattered and skill trumped gender in terms of the valuation of the goods—an unusual facet of this study. Of course, there are many contradictions embedded in the valuation of women’s labour, not least when it comes to the labour of the unfree (a subject I am considering deeply at the moment). How else might we think about value?

Stefan Hanß: Value regimes are complex and ambiguous, I agree, and subject to constant negotiation. We only start to understand how early modern making and material culture featured into the politics of life and the wider inequalities of the time. One particularly impactful development discussed in the article is that values of making became increasingly tied to virtues of makers. So, the material culture of making came to embody virtues of femininity, which in turn meant that such artefacts could embody and reproduce gendered values. I believe that much future work will unravel the troublesome history of material culture and its significance in establishing social, colonial, gendered and racial inequalities, as shown by your own pathbreaking work on material culture and race, Beverly, and the recent volume In-Between Textiles, 1400–1800.

How could the article’s discussion of gendered material values contribute to such future debates? The article shows that early modern gendered value regimes were deeply engrained in changing attitudes to making, for instance. This means that material culture ‘genders’ beyond symbolism. Making itself meant to remake life, and gendered values ascribed to material practices themselves may helped establish wider regimes of valorization. The repetition of such material practices then, sensu Judith Butler, could establish gender normativity. The more important it is for us, as historians, to uncover a shared and relational early modern world of making, and to use innovative methods, like microscopy or remaking for example, to visualize women’s work as astonishing cognitive and entrepreneurial achievements.

This article brings some fascinating examples to the wider debate on early modern working women. I think we gain some amazing details for what Amy Erickson calls the ‘economic partnership’ of early modern married couples, or Heide Wunder’s concept of early modern ‘working couples’. Historians of working women have also customarily framed female labour as underpaid and unskilled work with either cheap, old and used clothing or unprocessed raw materials. The Stuttgart receipts however show that many craftswomen championed high-end luxury crafts, and that the court of Württemberg was willing to pay immense sums to purchase such goods. As you say, this was a surprising find given the wider literature. The article also presents some important examples that challenge the widely established narrative that guilds pressured widows into quick marriages. Some widows operated for years and even decades, the Stuttgart receipts show, generating a fortune by producing and selling products and high-end goods. Most importantly, I think, this article shows the extent to which the ducal family’s consumerist expectations relied on the material expertise, knowledge, and creativity of working women, and the social potential of such dependencies for women who tried to remake communities and relationships through making when situating the products of their work, for instance, in the wider networks of female courtly patronage.

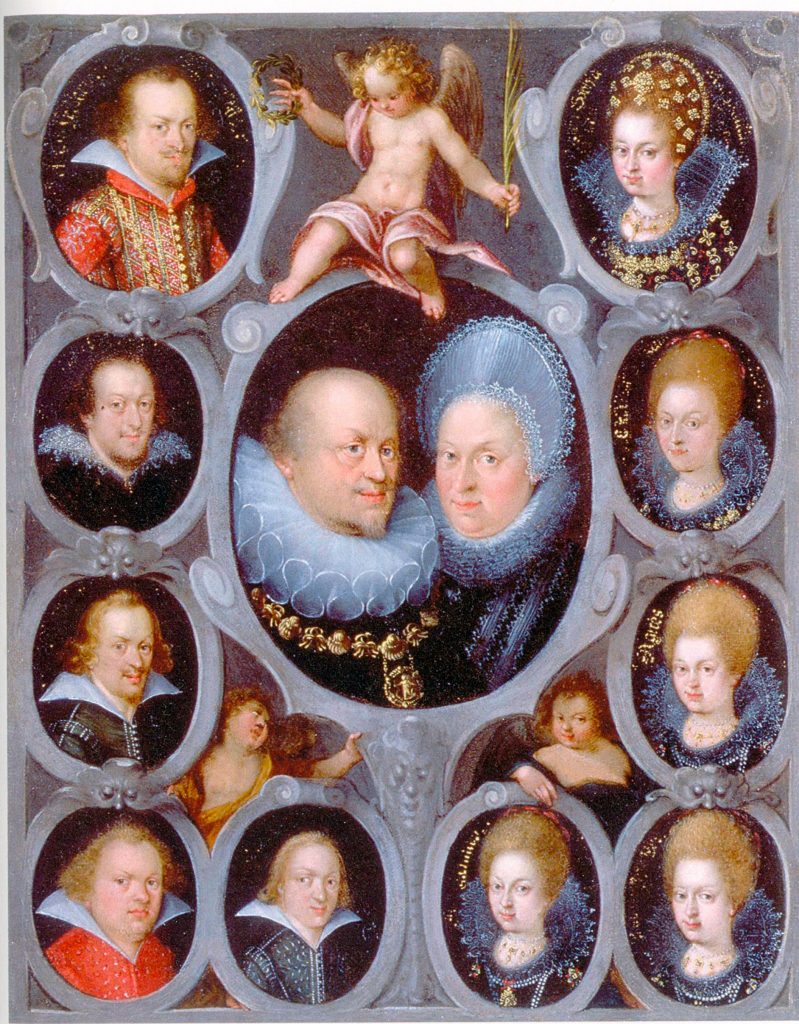

Pieter Isaacsz, Duke Friedrich I and Duchess Sibylla of Württemberg with ten of their children. Painting. 30.5 x 24 cm. Württembergisches Landesmuseum Stuttgart. © Wikimedia commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:85Familie_Friedrich_I.jpg.

Laura Gowing: Your argument that, both as makers and as wearers, women shaped material lives at court seems extendable to many other European contexts. How far do you think this aspect of the material Renaissance is a general one, and how much is specific to the Stuttgart case study?

Stefan Hanß: Women’s labour and industriousness in making, trading and consuming were key in widening consumer choices and making the material Renaissance. My reading of the Stuttgart receipts is influenced by Beverly Lemire’s study of early modern global trade and industriousness, your own work on apprenticeship, and Evelyn Welch’s vivid portrayal of Isabella d’Este as an active, strategic and versatile consumer, among others. In Shopping in the Renaissance, Evelyn Welch states that ‘in turning to the Italian Renaissance courts, wives, mothers, daughters and sisters suddenly appear with far greater clarity.’ This is reflected in the findings from the court of Württemberg.

Yet, the Stuttgart case study is specific in terms of the ways that Lutheranism linked material culture with the production of useful knowledge at that particular time. Also rather particular dynastic circumstances lend significance to the female body, and the material industriousness of the duchesses, to embody Württemberg rulership. After all, it was only after the sudden death of his childless second cousin, 39-year-old Ludwig, in 1593, that Friedrich surprisingly inherited a ‘threatened dynasty’ (Paul Sauer). While her husband’s predecessor had remained childless, Duchess Sibylla gifted Friedrich with altogether fifteen children throughout her life. This constituted her reputation as the ‘mother of the territory’ (Landesmutter) and lend further significance to the material practices of the duchess’s body. Also fierce constitutional conflicts between the duke and the estates provide a specific context for the Stuttgart receipts. The estates had to approve the court’s spending and after both Friedrich and Johann Friedrich had ruled for years with the de facto suspension of the diet, the estates increasingly opposed ducal financial politics. The estates restricted the means of the ducal family and reduced their commitment to cover debts, especially those related to courtly splendour and luxury. In light of such contested financial politics, the duchesses’ immense spending on the material appearance of their own as well as their extended bodies, as detailed in this article, was a powerful statement on ducal authority and agency. In addition to all this, it is the survival of an extremely detailed series of sources that offer the rather unique chance to recover the history of women as active makers, commissioners and purchasers in the German material Renaissance in unprecedented depth.

Beverly Lemire: Finally, I was intrigued to read analyses of the boundaries of women’s bodies, relational and porous, and the role of artefacts in these extensive possibilities. Where else might this lead?

Stefan Hanß: This idea is closely linked to the truly inspirational oeuvre of Natalie Zemon Davis, and her book chapter ‘Boundaries and the Sense of Self in Sixteenth-Century France’ in particular. Davis examines sixteenth-century women’s wills and argues that women’s detailed instructions on the distribution of personal artefacts, especially those worn close to their bodies, point to women’s strategic use of material culture to carve out a space of subjectivity, a sense of belonging and social relationships. Claudia Ulbrich and Gabriele Jancke introduced me to this powerful text as a student in a seminar on early modern self-narratives at the Freie Universität Berlin. Since then, this interpretation kept me thinking in particular regarding the links between material culture, the self and the ways that early moderns conceptualised and experienced their bodies as porous, unstable and relational. The Stuttgart receipts made me think that artefacts could extent women’s possibilities to participate in material exchanges that negotiated the social realm of personhood. Artefacts could extend women’s bodies themselves, and this was such a crucial material strategy of selfhood for both female consumers and makers at the court of Württemberg around 1600. I see the potential to link such considerations with the history of the senses and emotions, for instance in work on how perfumed artefacts related to emotional experiences in the early modern period; or how materials interacted with the physical materiality of the body and the extent to which matter, in early modern terms, enacted bodily porosity and instability. It would be such a joy to see the idea of porous, extended bodies further developed for different contexts in future studies!

Literature mentioned in this interview

Ågren, M. ‘Introduction: Making a Living, Making a Difference.’ In M. Ågren (ed), Making a Living, Making a Difference: Gender and Work in Early Modern European Society, pp. 1–23. Oxford, 2017.

Arnold, D. Y. ‘Making Textiles into Persons: Gestural Sequences and Relationality in Communities of Weaving Practice of the South Central Andes.’ Journal of Material Culture 23, no. 2 (2018): 239–60.

Davis, N. Z. ‘Boundaries and the Sense of Self in Sixteenth-Century France.’ In T. C. Heller, M. Sosna and D. E. Wellbery (eds), Reconstructing Individualism: Autonomy, Individuality, and the Self in Western Thought, pp. 53–63, 332–5. Stanford, 1986.

Erickson, A. L. ‘The Marital Economy in Comparative Perspective’. In M. Ågren and A. L. Erickson (eds), The Marital Economy in Scandinavia and Britain, 1400–1900, pp. 3–20. Burlington, 2005.

Fleischhauer, W. Renaissance im Herzogtum Württemberg. Stuttgart, 1971.

Gowing, L. Ingenious Trade: Women and Work in Seventeenth-Century London. Cambridge, 2022.

Handley, S. and J. Morgan (eds.) Environment, Emotion and Early Modernity (= Environment and History 28, no. 3, 2022).

Hanß, S. ‘Digital Microscopy and Early Modern Embroidery.’ In Writing Material Culture History, eds. Anne Gerritsen and Giorgio Riello, 2nd edition, pp. 214–21. London, 2021.

Hanß, S. ‘Feathers and the Making of Luxury Experiences at the Sixteenth-Century Spanish Court.’ Renaissance Studies 37, no. 3 (2023): 399–438.

Hanß, S. ‘Gendering the Material Renaissance: Women, Industriousness and the Female Body at the Court of Württemberg.’ German History 41, no. 3 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1093/gerhis/ghad031.

Hanß, S. ‘Material Encounters: Knotting Cultures in Early Modern Peru and Spain.’ The Historical Journal 62, no. 3 (2019): 583–615.

Landesmuseum Württemberg. Die Kunstkammer der Herzöge von Württemberg: Bestand, Geschichte, Kontext, 3 vols. Stuttgart, 2017.

Lemire, B. Global Trade and the Transformation of Consumer Cultures: The Material World Remade, c. 1500–1820. Cambridge, 2018.

Marín-Aguilera, B., and S. Hanß, eds. In-Between Textiles, 1400–1800: Weaving Subjectivities and Encounters. Amsterdam, 2023.

Ogilvie, S. A Bitter Living: Women, Markets, and Social Capital in Early Modern Germany. Oxford, 2003.

Rublack, U. ‘Craft, Labour and Cabinets of Curiosities: Rethinking the Body of the Artisan’, German History 41, no. 3 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1093/gerhis/ghad029.

Rublack, U. ‘Fluxes: The Early Modern Body and the Emotions.’ History Workshop Journal, 53 (2002): 1–16.

Rublack, U. ‘Performing America: Featherwork and Affective Politics.’ In Materialized Identities in Early Modern Culture, 1450–1750: Objects, Affects, Effects, eds. Susanna Burghartz, Lucas Burkart, Christine Göttler and Ulinka Rublack, pp. 187–229. Amsterdam, 2021.

Sauer, P. Herzog Friedrich I. von Württemberg, 1557–1608: Ungestümer Reformer und weltgewandter Autokrat. Munich, 2003.

Smith, K. Material Goods, Moving Hands: Perceiving Production in England, 1700–1830. Manchester, 2014.

Smith, P. H. The Body of the Artisan: Art and Experience in the Scientific Revolution. Chicago, 2004.

Ulbrich, C. ‘Unartige Weiber: Präsenz und Renitenz von Frauen im frühneuzeitlichen Deutschland.’ In C. Ulbrich, Verflochtene Geschichte(n): Ausgewählte Aufsätze zu Geschlecht, Macht und Religion in der Frühen Neuzeit, ed A. Griesebner et al., pp. 15–45, Vienna, 2014.

Vermeulen, J., S. Hanß and U. Rublack, ‘“In Feather-Working, the Only Limitation is One’s Own Imagination”: Julien Vermeulen, Stefan Hanß and Ulinka Rublack on the Past and Future of Feather-Working.’ Microscopic Records: The New Interdisciplinarity of Early Modern Studies, c.1400–1800: Blog. 21 October 2019. https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/microscopic-records/2019/10/21/in-feather-working-the-only-limitation-is-ones-own-imagination-julien-vermeulen-stefan-hans-and-ulinka-rublack-on-the-past-and-future-of-feather-working/.

Welch, E. ‘Sites of Consumption in Early Modern Europe.’ In F. Trentmann (ed), The Oxford Handbook of the History of Consumption, pp. 229–50. Oxford, 2012.

Welch, E. Shopping in the Renaissance: Consumer Cultures in Italy, 1400-1600. New Haven, 2005.

Wiesner, M. E. Working Women in Renaissance Germany. New Brunswick, 1986.

Wunder, H. He Is the Sun, She Is the Moon: Women in Early Modern Germany, transl. by T. Dunlap. Cambridge, Mass., 1998.

Featured image: Geertruydt Roghman. A Woman Spinning, c.1640–57, engraving, 20.8x16.5 cm. ©The Metropolitan Museum New York, 56.550.5, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection.

0 Comments