Student spotlight: Alexander Hurlow

Norman Identity in Capetian France (1204-c.1337): The Chronique de Normandie and Établissements de Rouen

PhD researcher, Alexander Hurlow, discusses the Rylands’ copy of the ‘Chronique de Normandie’, and how his JRRI funded MA helped to lay the groundwork for his doctoral thesis, which he successfully defended in June 2020.

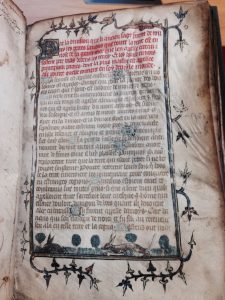

Manchester, John Rylands Library, MS. fr. 56, f. 5r.

In 2015 I was granted funding for my Medieval and Early Modern Studies MA by the JRRI. It was during this time that I first became acquainted with Rylands, French MS 56, an Old French chronicle of the dukes of Normandy known as the Chronqiue de Normandie. I was able to identify several codicological and textual features that formed the basis of my AHRC funded PhD project exploring Norman identities in the thirteenth century.

The Chronique de Normandie is an Old French prose history of the dukes of Normandy, tracing their Trojan origins up to the reign of King John of England (1199-1216). Produced originally in Northern France, the Chronique survives today in eighteen manuscript copies housed in archives scattered across Europe. The vernacular medium of the Chronique allowed each copy to be updated and altered to fit the needs of those who commissioned it. As a result, there is wide variation between the various copies that provide a kaleidoscope of views on aristocratic identity in Normandy and Northern France in the thirteenth century.

The thirteenth century was a time of political upheaval in Normandy. The year 1204 saw the conquest of duchy by the French king, Philip Augustus (1180-1223). Previously at the heart of an Anglo-Norman kingdom stretching back to 1066, Normandy was now annexed to the French royal domain. The thirteenth century saw the French kings acquire significant land, wealth and political muscle which they had lacked in previous centuries. This led to increasing centralisation which in turn has led modern historians to view this as a critical period in the building of the French state. Traditional historiography has often emphasised the ease with which Normandy accommodated its new rulers, with Norman identities subordinated by a burgeoning French ‘national’ identity. One of the aims of my PhD project was to challenge this assumption by analysing of the various visions of the past presented in the Chronique. The evidence shows that Norman communities often remembered events, figures and myths in ways that contrasted sharply with those of their French counterparts.

The Chronique held at the Rylands provides a good case study for the themes of the project. It dates to the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century and displays several unique features. It extends slightly further than other copies of the Chronique, up to the year 1217, recording the failed invasion of England by Prince Louis of France (later Louis VIII, 1223-1228). The anti-French sentiment implied by concluding with a French military failure is also stressed in an extended account of Richard the Lionheart’s exploits on the Third Crusade. According to the Rylands Chronique, such was Richard’s prowess and generosity that the French king became jealous and abandoned the crusade. Despite being first and foremost a king of England, Richard is presented as a Norman hero. He rushed back from crusade to defend Normandy against the French king and requested that his heart be buried in Rouen Cathedral because of the love he had for the duchy. The Rylands Chronique provides a rare, pro-Richard, account of the Third Crusade from the continent. The narrative embeds Norman history within the ‘national’ struggles between England and France that led up to 1204.

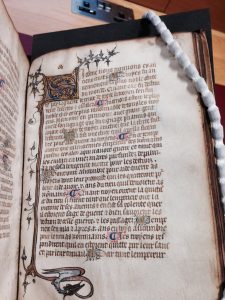

Manchester, John Rylands Library, fr. 56, f. 65r.

The ‘national’ perspective is one way of interpreting the Chronqiue’s narrative. Anglo-Norman landholders were forced to choose between their English and continental lands after 1204. A history that kept alive the memories of when the two lands had been united would perhaps have appealed to such families. However, the greatest landholders chose to preserve their larger and more lucrative English possessions. The void left by the Anglo-Norman magnates was filled by a second tier of Norman barons who now became the leading families of the region. Their interests were perhaps less focused on ‘national’ struggles but on regional, local and individual concerns and this too can be detected within the Chronique. For example, William de Mortemer, a knight with lands in the Pays de Caux and Roumois, is singled out for praise. He is noted for his brave defence of Verneuil for Richard I against Philip Augustus in 1194 and again at Arques for King John in 1202. William’s actions could be interpreted on a ‘national’ level, part of the defence of the Anglo-Norman realm against the French, but he also had good personal reasons for defending the duchy in which his lands lay. The knowledge that William’s defence would ultimately have been in vain perhaps mattered less to the copyist of the Chronique than celebrating the brave defence of the region by local Norman knights.

It was not only the knights and aristocracy of Normandy we see being celebrated for their defence of the duchy. Another version of the Chronique, Cambridge University Library, Ii. 6. 24., describes the women of Rouen throwing rocks, boiling water and tar from the walls of the city during Louis VII’s siege in 1174. Again, this can be read both as part of the ‘national’ struggle between the Anglo-Norman realm against the French and a source of local pride that quickly passed from oral tradition into historical narrative. The episode also highlights the increasing importance of towns and cities to the defence and prosperity of the region. In the late thirteenth century a new urban elite emerged, burgesses, whose families were involved in the administrative and judicial functioning of the city and its hinterlands. These urban elites acquired several privileges and customs that in the absence of a duke came to embody the identity of the duchy. The reconfirming of these privileges by the French king in 1204 was considered significant enough to be noted by the Chronique, which states that Philip Augustus swore to uphold the ‘laws and customs that King Henry, son of the Empress Matilda and King Richard his son had observed’. Some scholars have suggested that the Rylands Chronique was in fact produced by a lawyer from Rouen and if so, he may have been thinking more locally when he spoke of ‘laws and customs’ granted by the former dukes. At the same time as he swore to uphold Norman customs it is likely that Philip Augustus also reconfirmed the Établissements de Rouen, the charter which confirmed communal status and specific privileges for the city of Rouen. Once again, various levels of identity can be filtered through the Chronique. The importance of custom and its links to the ducal past contribute to our understanding of the construction of regional, local and individual identities within Normandy.

It is important to note that the Rylands Chronique is only one example from seventeen other manuscripts. Furthermore, the events of 1204 also saw an influx of non-Norman aristocrats who were recipients of confiscated lands of English landholders. The influence of these families cannot be discounted and other copies of the Chronique display a greater willingness to embrace a combined Norman and French history. Similarly, over the course of the century Normans began to play an increasing role in French royal administration. These added layers of complexity only serve to highlight that Norman identities did not emerge unscathed or unchanged by the events of 1204 nor did they merge seamlessly with French ‘national’ identity. What is found is not a simple case of a Norman identity opposed to a French one, but multifaceted and overlapping visions of the past. Through appeals to the ducal past, the crusading past and unique oral traditions it appears Norman families, cities and individuals were still capable of using their past to negotiate and rationalise the uncertain political and social landscape of the thirteenth century.

alexander.hurlow@postgrad.manchester.ac.uk

@AlexHurlow

0 Comments