Astley Hall Virtual Tour

The author of this blog entry is Dr Abigail Greenall, Early Career Research Fellow at The John Rylands Research Institute, University of Manchester.

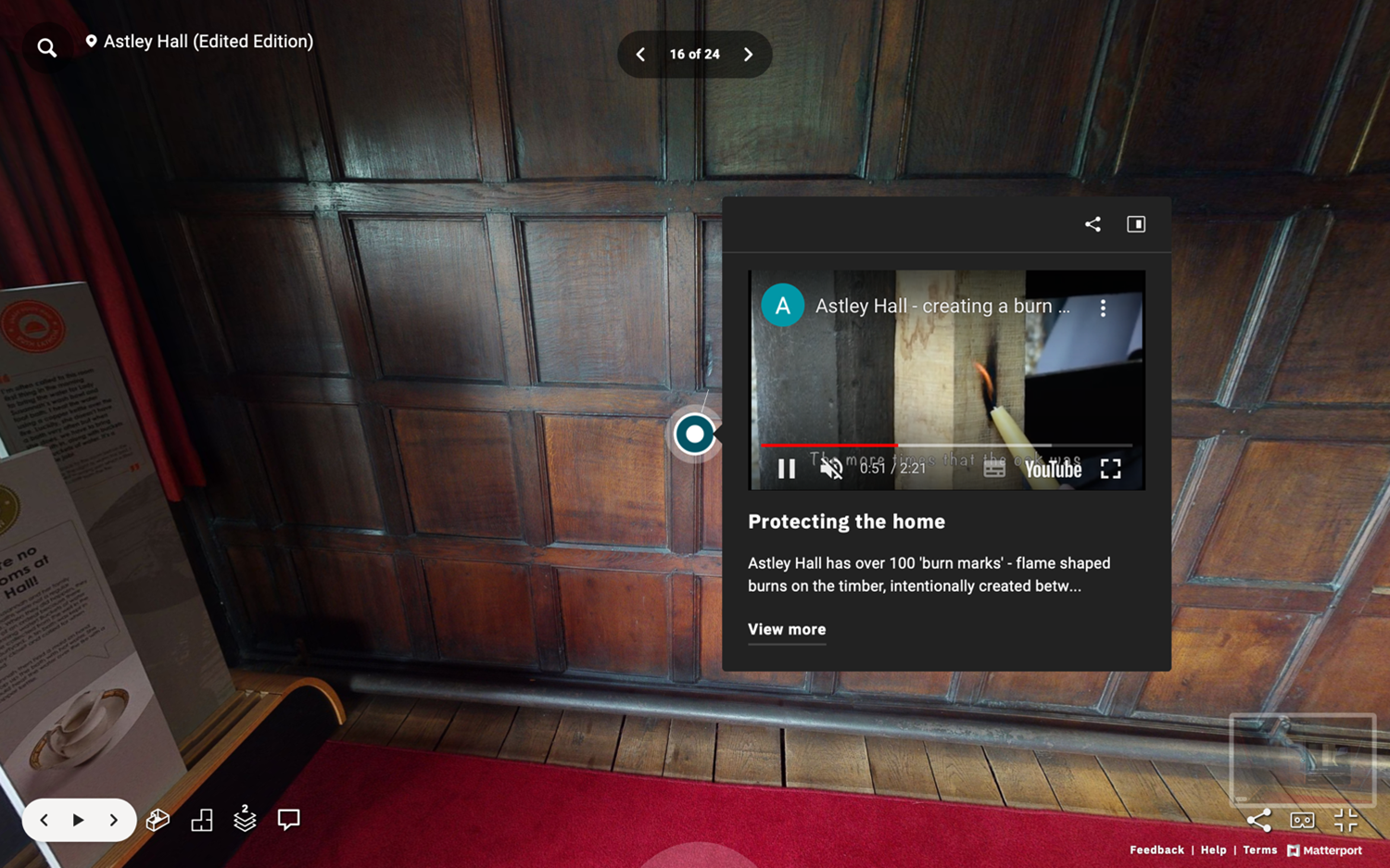

For some years now, Sasha Handley and I have shared a fairly healthy obsession with apotropaic, or evil averting, burn marks. That is to say, we have scoured historic houses in the north west for flame-shaped marks on timber-framework and oak furniture. Largely made in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, these curious marks have been found in houses and barns across northern Europe and North America, and were either intended to convey good luck or designed to protect families from disease, fire, storms, and supernatural forces through sympathetic or ritual magic.1 Either way, they probably comforted and assured the people who made them.

Fig. 2. Burn mark on the oak panelling in the Oak Bedroom at Astley Hall. Photo credit: Abigail Greenall.

In 2019, we received a tip-off that some burn marks had been found on the early modern beds at Astley Hall, Chorley. Given our mutual interest in supernatural beliefs, and Sasha’s particular interest in sleep related practices, we made a trip to Astley Hall. As it turns out, the Education & Engagement team at Astley Hall had already noticed public interest in its historic graffiti and burn marks but they had not been systematically surveyed and analysed.

We decided to work together on a project to better understand the marks at Astley. I secured funding from the North West Social Science Doctoral Training Partnership for a twelve-month internship the following year. September 2020 was an exciting time for Astley Hall. Chorley Council (who own the Tudor/Jacobean house) had announced plans to carry out a £1.1 million restoration project, and the curators were set to rejuvenate the Hall’s historic interpretation. My role was to help Mitch Robinson (Education & Engagement) and Amy Dearnaley (Curator) uncover and exhibit Astley’s historic graffiti.

I led an archaeological survey of the entire house (spanning three floors) and its collection of early modern furniture to uncover and record burn marks. 121 newly discovered burn marks were measured and recorded over a three-month period. Reports of this data were drawn up and are now stored at Astley Hall for future researchers.

Presenting this data to Astley’s visitors in an accessible and captivating way was no mean feat. Burn marks are notoriously tricky to explain. Though there is plenty of archaeological evidence to suggest that diverse groups of people repeatedly marked their homes and furnishings in this way, they don’t appear to have written anything about them. Explaining this ritual practice thus requires an approach and theoretical framework that is sensitive to the thoughts and feelings of different people in specific historic contexts. Such conceptual unpacking is a lengthy and wordy process. There was only space for a brief introduction to them on the new interpretation panels that Amy was in the process of writing. We needed to find another way to show the public how burn marks were made and contextualise them within the social, emotional, and religious practices of the early modern period.

Our solution was to use a digital humanities approach—an idea that came to me during the fifth masterclass of Microscopic Records, a British Academy event that took place at the University of Manchester in October 2020 and convened by Stefan Hanß. In this masterclass Luca Scholz gave a practical demonstration on how to generate 3D models from photographs of artefacts, buildings, and people in the photogrammetry software Agisoft Metashape. I came away from the event excited by the potential role that 3D modelling could play in capturing and conveying the extra interpretative information we needed at Astley Hall.

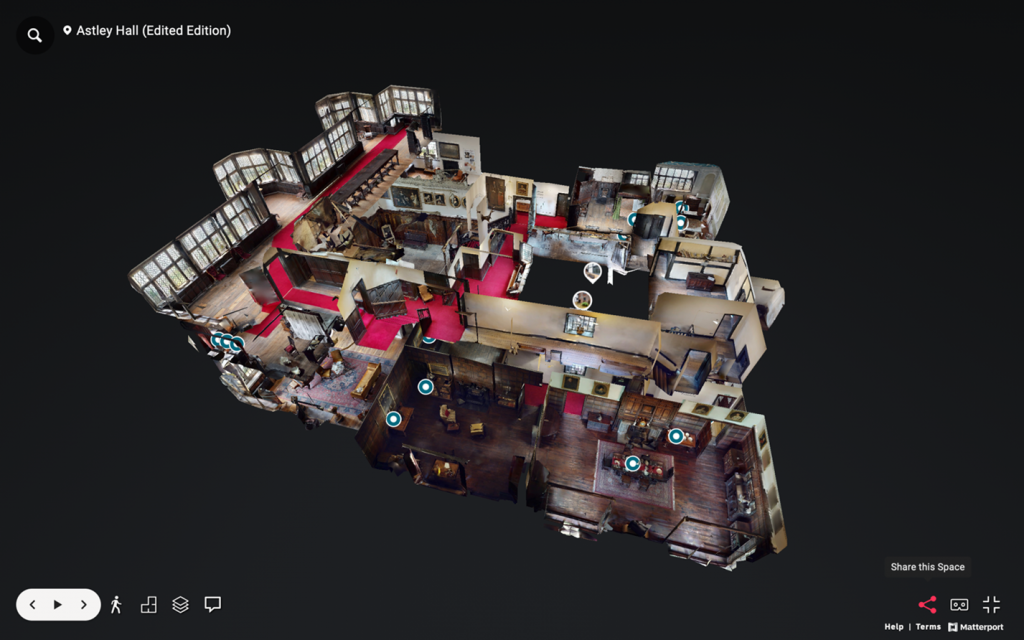

After making a few enquiries, I met with Kostas Arvanitis, who founded Virtual Tours: Powered by Matterport during COVID-19. This project allows university students, staff, and the wider public to access museums, galleries, and heritage sites in Greater Manchester from wherever they are in the world. Kostas agreed to include Astley Hall in the Virtual Tours project. I pitched the idea to Dave Tetlow, Astley’s Heritage Manager, who was keen to get involved.

Astley Hall was one of the first heritage sites in the Virtual Tours project. It was also the largest space the team had taken on. John Piprani, who manages the technical side of the Virtual Tours project, had the brilliant idea to run the Astley Hall by Virtual Tours collaboration as a training session for Archaeology students interested in heritage.

In May 2022, John and an enthusiastic group of assistants—Laura Thompson, Rebecca Oldfield, and Stephanie Rylance—made the trip out to Astley Hall with the Matterport camera in tow. With this impressive (if slightly intimidating) piece of kit we took over 400 360° photos, known as scans, of all publicly accessible rooms, and experimented with light and height to recreate the experience of being in the space. We captured the whole house in just two days, thanks to this wonderful group of researchers.

Generating the 3D model of the Hall was easy, even if we did encounter one or two glitches in the process! Matterport technology cleverly stitches together each scan to create a space that you can move through virtually, toggle between floors, and view or measure floor plans. The team’s hard work, reflected in the large number of scans, paid off – the Matterport app produced a good quality 3D model.

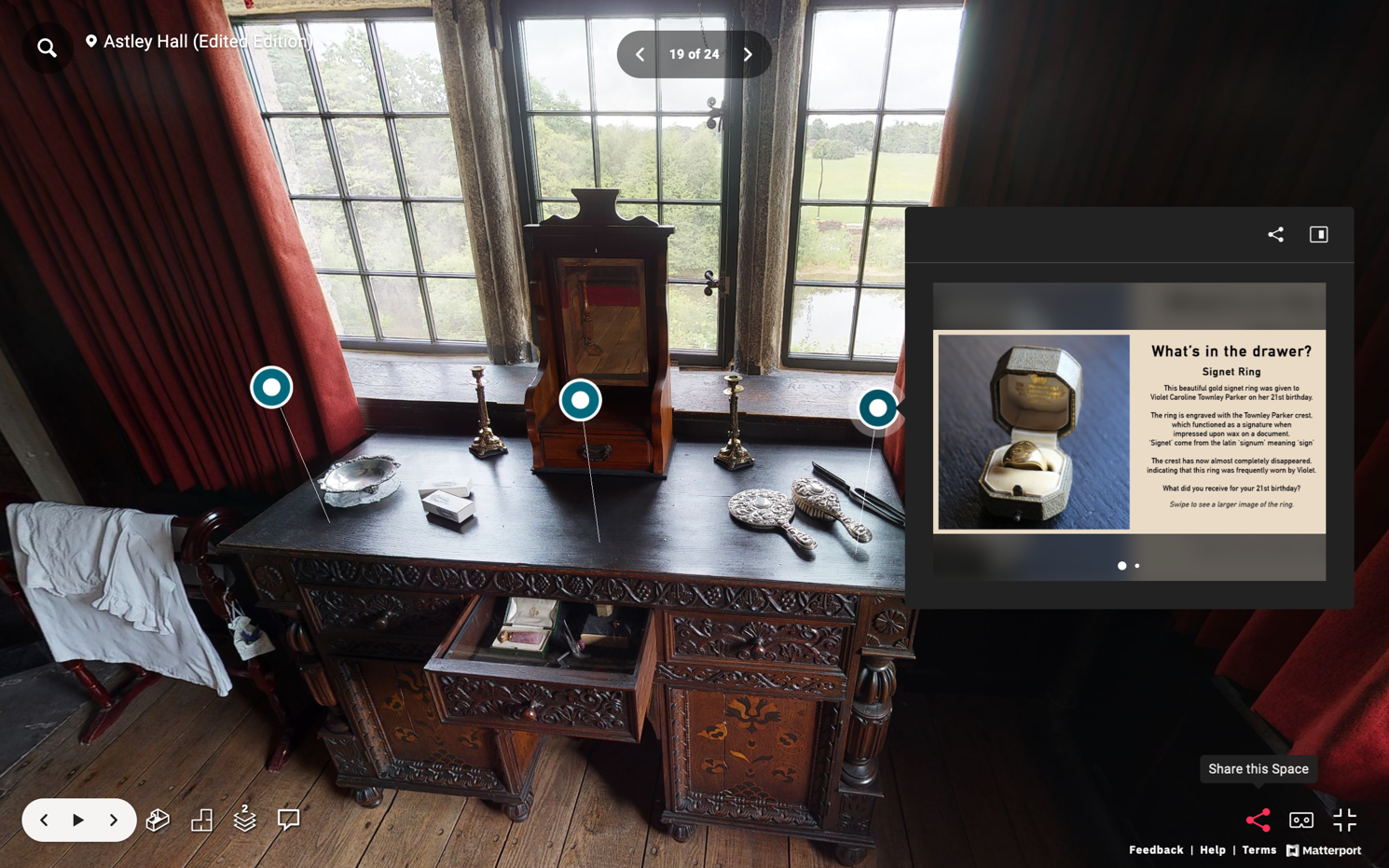

Matterport offers additional features for a next-level virtual experience. Some have been especially useful for my task of exhibiting extra interpretive information about Astley Hall and its burn marks. “Story Mode” allowed us to create a simple, mobile friendly, guided tour with on-screen titles and room descriptions. “Mattertags” meant we could highlight interesting features and add contextual details about less-known items in Astley’s museum collections. The capacity to upload multimedia files allowed us to show visitors images and videos, such as our short-film of a recreated burn mark:

There’s plenty of scope for the Education & Engagement team to add interpretive content to the 3D model as they grow in confidence using it. As a member of the Virtual Tours collective, Astley Hall now have access to all the bells and whistles that come with Matterport’s Professional plan. Matterport have recently introduced a new feature called “Views”. Accounts that have the Professional plan can create up to 10 unique “Views” of the 3D model. Each view has its own tours and tags. This gives Mitch, in particular, the potential to create multiple school-packages tailored to different key-stages in the national curriculum. It also allows Amy to create distinctive tours of Astley’s collections and architectural features at different points in their public programming schedule, which changes according to the seasonal cycle and festive seasons.

Other features of the Professional plan suggest that Matterport have responded to concerns about potential threats 3D models pose to privacy in commercial settings and to the integrity of the arts and heritage sector. The “Blur Brush” is a new editing tool that Matterport have developed to boost their clients’ agency by giving them the power to obscure human faces and objects. This was particularly important for Mitch and Amy who are responsible for protecting Astley’s museum collections. Keen-eyed virtual tour-goers might notice a number of obscured paintings, whose copyright holder is unknown, in the dining room. The blur brush allowed us to keep the Victorian dining room in the 3D model whilst ensuring that it complies with copyright laws.

Fig. 9. View of dining room with obscured paintings. Still image of 3D model.

It is important not to shy away from such concerns and potential pitfalls if digital humanities is to benefit the arts and heritage sector. I was prepared to grapple with a number of practical questions about the role of 3D imaging software in museum environments, which were first highlighted to me during the course of Microscopic Records’ fifth masterclass, and sure enough, they have reared their heads at various points over the last 3 years. In the beginning, Amy, Mitch, and I had to think carefully about how we could use the 3D model to enhance and not take away from the experience of visiting Astley Hall in-person. We have been careful to create interpretative content that supplements, rather than repeats, the new and improved interpretation panels, which have now been printed and installed in the rooms. On more than one occasion we had to consider rights of use. An entire room had to be removed from the model because it contained protected information on individuals from Chorley who fought in the world wars and artwork that we could not show under UK Copyright laws. We have also struggled to keep pace with technological developments. In the end, we had to change our original plan to upload multimedia content via SlideShare as it was no longer compatible with Matterport software. But there has always been a solution to these woes. Thanks to the generosity of time, expertise, and enthusiasm of everyone involved we have overcome every bump in the road and created a Virtual Tour that we are happy to share. We hope that it gives every (online and in person) visitor the chance to learn something new about everyday life at Astley Hall over the last 400 years.

Dr Abigail Greenall

If you have any suggestions that might help us improve 3D Astley in the future, please leave us your feedback here.

1 These are two potential explanations. For more on burn marks and household magic, see John Dean and Nick Hill, “Burn Marks on Buildings: Accidental or Deliberate?,” Vernacular Architecture 45, no. 1 (2014): 1-15. DOI: 10.1179/0305547714Z.00000000021. Brian Hoggard, Magical House Protection: The Archaeology of Counter-Witchcraft (Oxford: Berghahn, 2020), Chap. 7. Owen Davies and Ceri Houlbrook, Building Magic: Ritual and Re-enchantment in Post-Medieval Structures (Cham: Springer, 2021).

0 Comments