New Directions in the History of the Body – Holly Fletcher in Conversation with Ulinka Rublack

In this new series for The Bodies, Emotions and Material Culture Collective blog, Dr Holly Fletcher interviews leading historians on the subject of the history of the body. For this post, she spoke to Professor Ulinka Rublack about her previous and current work, as well as future directions in the field.

Ulinka Rublack is Professor of Early Modern European History at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of the British Academy. She has published widely on sixteenth and seventeenth-century culture, including pioneering publications on early modern material culture, gender history and the history of the body. Her book Dressing Up: Cultural Identity in Early Modern Europe (OUP, 2011) won the Bainton Prize and in 2018 the Humboldt- and Thyssen Foundations jointly awarded her the Reimar-Lüst Prize, a life-time achievement award for outstanding research and fostering academic exchange. In 2019 her work as a historian and her book The Astronomer and the Witch: Johannes Kepler’s Fight for his Mother (OUP, 2015) were recognised with Germany’s most prestigious prize for historians, the Deutsche Historikerpreis.

Ulinka Rublack is Professor of Early Modern European History at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of the British Academy. She has published widely on sixteenth and seventeenth-century culture, including pioneering publications on early modern material culture, gender history and the history of the body. Her book Dressing Up: Cultural Identity in Early Modern Europe (OUP, 2011) won the Bainton Prize and in 2018 the Humboldt- and Thyssen Foundations jointly awarded her the Reimar-Lüst Prize, a life-time achievement award for outstanding research and fostering academic exchange. In 2019 her work as a historian and her book The Astronomer and the Witch: Johannes Kepler’s Fight for his Mother (OUP, 2015) were recognised with Germany’s most prestigious prize for historians, the Deutsche Historikerpreis.

Holly Fletcher is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the University of Manchester on the Wellcome Trust funded project ‘Sleeping well in the early modern world: an environmental approach to the history of sleep care’. Her work focuses on the history of the body and its entanglements with the material world and her research has been published in leading journals including Gender & History, German History and Food & History. Her article ‘“Belly-Worshippers and Greed-Paunches”: Fatness and the Belly in the Lutheran Reformation’ won the 2021 German History Article Prize. She completed her PhD at the University of Cambridge in 2020 for which she examined the cultural significance of body size, fatness and thinness in early modern Germany.

Holly Fletcher is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the University of Manchester on the Wellcome Trust funded project ‘Sleeping well in the early modern world: an environmental approach to the history of sleep care’. Her work focuses on the history of the body and its entanglements with the material world and her research has been published in leading journals including Gender & History, German History and Food & History. Her article ‘“Belly-Worshippers and Greed-Paunches”: Fatness and the Belly in the Lutheran Reformation’ won the 2021 German History Article Prize. She completed her PhD at the University of Cambridge in 2020 for which she examined the cultural significance of body size, fatness and thinness in early modern Germany.

Holly Fletcher: Your article, ‘Fluxes: The Early Modern Body and the Emotions’ appeared in History Workshop Journal over twenty years ago and continues to be a source of inspiration for both students and scholars today. It is a piece that I return to time and again and which I have used to introduce numerous undergraduates to the subject of early modern bodies. Your account of the importance of flows, of both bodily fluids and emotions, offers an accessible entry point into early modern perceptions of the body and health, and through your discussion of the bodily significance of material and emotional exchange you show how the body can be a lens through which to study early modern communities at a broader scale. The part that I find students sometimes struggle to come to terms with is your question, ‘may it have been the case in the early modern period not only that bodily existence was conceived of differently from today, but also that this body actually behaved differently?’ How would you respond to this question today, in light of how scholarship concerning early modern bodies has developed, as well as your own research experience, in the twenty years since you first posed it?

Ulinka Rublack: I continue to think of bodies as entangled with the social and political, and hence think that bodies clearly behave differently in many respects. Of course, there are continuities and trans-cultural similarities that also loom large when you think about basic patterns of child development, for instance, or about physical processes relating to ageing. But I think we have become ever more attuned to the ways in which bodies can behave very differently, and in relation to different diets, or historically specific labour regimes, to other environmental factors such as pollution but also in relation to how community, friendship and love are lived in sensory ways. The intersectionality of gender, race and class has gained much more attention in the past decades to understand bodily experiences and regimes, and that is crucially important, alongside far more work on the history of the senses and of food. Our current concern with the ways in which the use of phones and media changes childhood as well as with rising calorie intake and a lack of opportunities to move are also testimony to the importance of charting how bodies feel and behave differently—they can become differently skilled and de-skilled, as Marcel Mauss pointed out, and change can be rapid and fundamental.

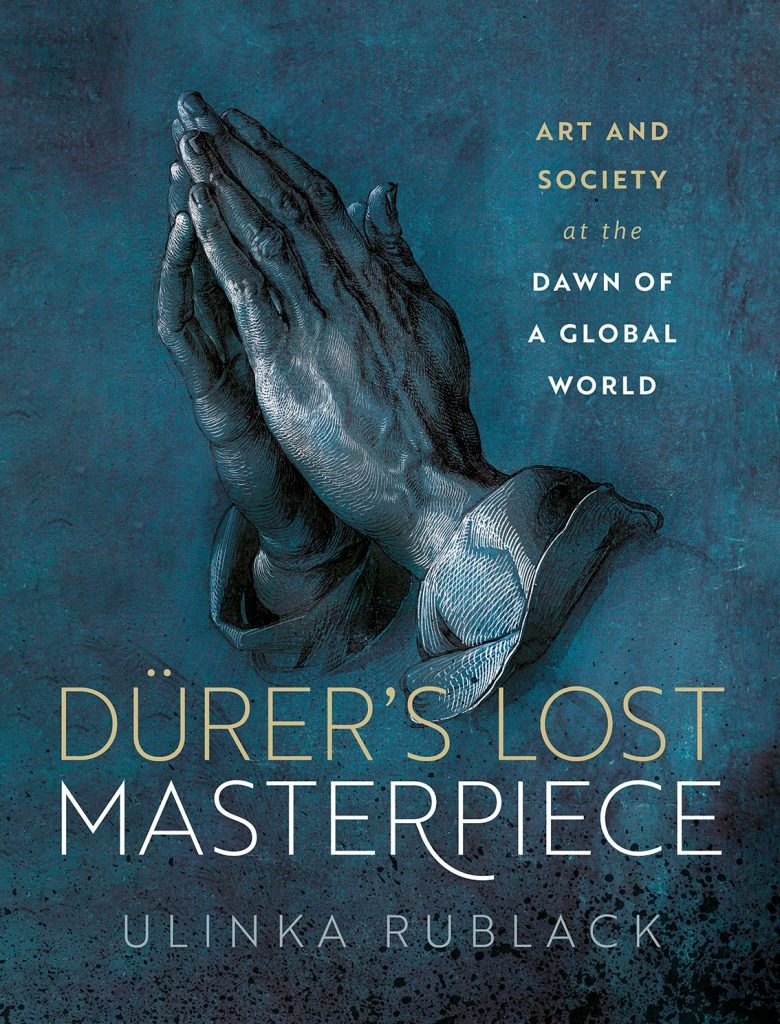

HF: In recent years much of your research has centred around early modern material culture, including your latest book Dürer’s Lost Masterpiece: Art and Society at the Dawn of a Global World. Would you say that your interest in matter and materiality evolved out of your engagement with bodies and embodiment? And what do you think the history of the body has to offer disciplines such as art history and material culture studies?

UR: Yes, these are very helpful questions to reflect on, thank you for developing them. I have always approached human subjectivity holistically and looked for the interrelationship between body and mind. Next, I began to see ever more acutely the importance of arguing that subjectivity develops not only in relation to other people and human institutions, but to a changing material world. I was particularly interested in how accelerated levels of making and consuming since the Renaissance reshaped bodily experiences but also how materials served to express aspects of humanity. This led to an interest in the relationship between humans and agentive animal matter as well, because I could see that Renaissance people were so drawn to an adornment with feathers, for instance, that was very novel. So my question became how culture is created in interchange with such materials and the ways in which they are experienced and performed by bodies, and this resulted in a very different account of the Renaissance than one aesthetically focused on painting, sculpture and architecture.

In relation to Dürer we have an artist who clearly was extremely in touch with his body and bodily changes over a lifetime and who used the image of his body extensively in his art in a self-identifying manner. My book focuses on his experience of the process of painting. This means moving away from an analysis just of the product of his work and its iconography, to ask what it meant for him to paint, what substances he dealt with and how, how physically engaged he was in painting, and what therapeutic and natural philosophical meanings his materials could be bound up with. We tend to think of Dürer as a print-maker and a man of the eye—but ambitious paintings that took a long time, such as altarpieces, were far more immersive experiences. I have tried to restore Dürer’s world as one saturated in natural dyes and colours, which he cared a lot about, from his coats to his pigments, and which were related to how he gained visibility or could balance his temperament. It is a different picture of the “master of the black line”!

My interest in labour regimes and the lives of artists found expression in this recent open access article. This also shows what it means to move on from the analysis of a product (in this case a cabinet of curiosities) to understanding the processes of how it was made. I see this closely interlinked with my work on Fluxes: it looks at a particular community of artisans and reconstructs how the emotional and social interrelated in their productive lives, crucially implicating their bodies in terms of their pleasures and pain.

HF: As part of your work on material culture you have conducted extensive research into early modern clothing practices and fashion cultures, including for your monograph Dressing Up: Cultural Identity in Early Modern Europe and your latest project The Triumph of Fashion, a forthcoming book on the rise of fashion in different parts of the globe from 1300 onwards. Fashion theorist Joanne Entwistle has written that ‘human bodies are dressed bodies’ since most people spend the majority of their lives wearing some form of clothing. The experience of the body is thus shaped by practices of dress and adornment; clothing acts upon the body, affecting one’s posture, movement, and even their physiological development. Given this intimate connection between dress and the body, is a global history of fashion necessarily, to some extent, a global history of bodily perception and experience? And does the significance of the body for fashion vary across time and in different parts of the globe?

UR: Yes, absolutely. The influence of Muslim and Christian conversions in this period meant that ever more people on the globe dressed and revealed less of their bodies. But dress practices differed significantly between and within cultures, while there is also much transcultural coherence, for instance in an attraction to luminosity and shine in adornment, or an emphasis on the elongation of the body to claim authority. I am currently interested in outerwear and masculinity, and the way in which long coats could provide a distinct physical experience and envelopment. This means moving away from a focus on garments to experiences of the worn.

HF: The move towards global perspectives has been deeply influential in recent historical scholarship and has clearly been a defining factor for your two latest projects. What future directions do you anticipate for the history of the body?

UR: The history of the twenty-first century is clearly turning out to be very different of what we had hoped for. So it will continue to be important to write politics into the history of bodies—as in Patricia Hill Collins’ new book Lethal Intersections, and to ask historically about experiences of violence, resistance and community. A focus on environmentally embedded bodies is likewise cutting edge in making us think about inequalities in experiences, as is an emphasis on labour. At the same time, it continues to be important to recognise the creativities, pleasures and imagination that interlinks with the bodily, and to celebrate those.

Featured image: Detail of Dürer’s figure from an early seventeenth-copy of the Heller altarpiece. Jobst Harrich, oil on panel, 189x138 cm, 1614 © Historisches Museum Frankfurt. Photo: Horst Ziegenfusz.

0 Comments