A closer look at the Manchester Observer (1819-1822)

Dr Janette Martin, curator of our current exhibition Peterloo: Manchester’s Fight for Freedom, writes:

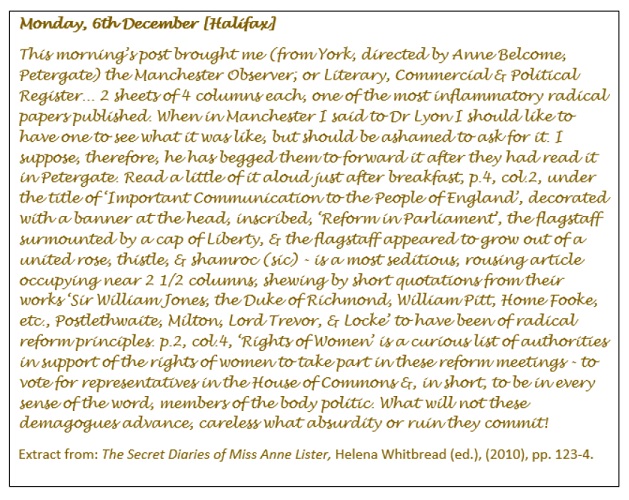

The spring and summer of 1819 saw radical speakers criss-crossing the country holding large meetings to raise support for parliamentary reform and other radical causes such as repeal of the Corn Laws. This caused great alarm and uneasiness amongst the authorities in Manchester and across the rapidly industrialising towns and cities of the north. A sense of this fear is captured in the diaries of Anne Lister of Shibden Hall, near Halifax. Anne Lister (1791-1840) was a wealthy Tory landowner who, unusually for the time, was not married and retained control of her own economic interests. Lister wrote disparagingly of the growing reform movement in her diaries, noting that trouble was expected in her home town of Halifax and that troops were billeted there. After the massacre at St Peter’s Field, she became curious about the leading radical newspaper, the Manchester Observer and asked friends to send her a copy as she ‘would be too ashamed to ask for it’. Her worst suspicions were confirmed – she did find it inflammatory and full of seditious, rousing articles.

Portrait of Anne Lister (1791-1840), by Joshua Horner, ca. 1830. Copyright Calderdale Museums & Galleries

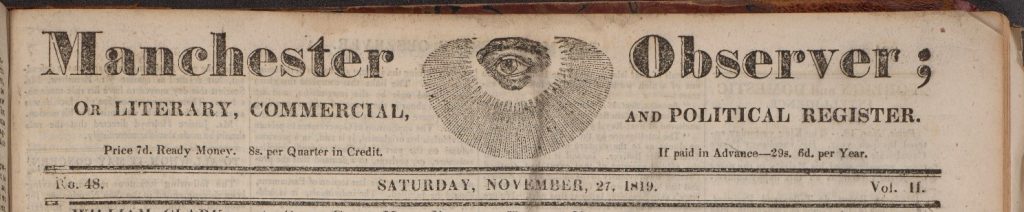

The Manchester Observer remains synonymous with the Peterloo Massacre. James Wroe, the Observer’s editor, had invited Henry Hunt to Manchester to speak that ill-fated day in August, and he himself coined the satirical name ‘Peterloo’. John Saxton, one of the Observer’s reporters, was on the hustings when the military rode into St Peter’s field. He was arrested and imprisoned. Saxton stood trial with Hunt at York Assizes but, unlike Hunt, he avoided a prison sentence because the jury accepted his defence that he was a reporter and not a participant. Until it was shut down in 1822, the pages of the Manchester Observer doggedly campaigned for justice for the victims and their families. Its influence stretched across the key cities and towns of northern England and copies were also sold in Birmingham. After only 12 months its circulation was 4,000 copies. To modern ears that might sound small but, as newspapers were expensive (thanks to a much-hated newspaper tax) copies would be bought collectively and circulated amongst friends. They were also read aloud thereby reaching a much wider audience than the circulation figures would suggest.

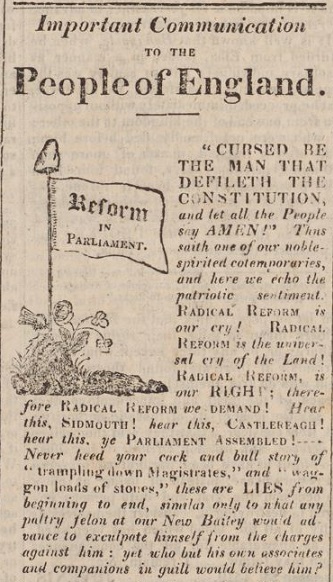

Example of the populist editorial style and the iconography of the cap of liberty, the thistle, rose and shamrock that so enraged Anne Lister. The Manchester Observer, 27 November 1819, Copyright the University of Manchester Library

The language and style of the Manchester Observer was aimed at the growing numbers of literate working classes. It was founded by James Wroe, John Knight and John Saxton, a group of non-conformist radicals who called for a reform of the Houses of Parliament. Their brand of radicalism was borne out of ideas underpinning the French revolution and stimulated by long years of war and high taxation, rising bread prices, trade slumps and the all-around squalor of the industrialising cities. Manchester Observer editorials focused on key radical issues and, for a period, were headed ‘Important Communications to the People of England’. Each was illustrated with a striking visual motif of a flag bearing a slogan. As the diary entry from Anne Lister below illustrates, both the slogans and the iconography of the flags were highly provocative to the Tory establishment. These editorial messages were designed to read aloud, with helpful capital letters, italics and exclamation marks to indicate which words and sentiments should be emphasised. Before literacy became widespread there was a common practice of communal reading where the most fluent would read the news aloud to a gathered audience, whether in a pub, workshop or around a domestic fire. (Interestingly, Anne herself describes how she read parts of it aloud!)

* Thanks to Steve Crabtree (Calderdale Museums and Galleries) for alerting me to Lister’s comments on the Manchester Observer

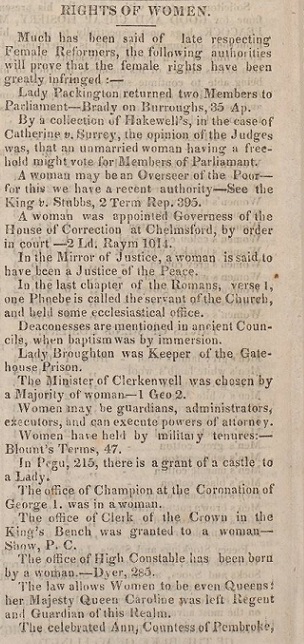

Her diary entry for 6 December 1819 (reproduced above) describes in detail her encounter with a copy of the Manchester Observer and from her comprehensive description we know that she was reading the issue dated 27 November 1819. Anne Lister’s hostility to the reform movement is not surprising and yet, to contemporary eyes, her deep resentment towards the fledgling campaign for the rights of women is less understandable. She herself led an unconventional life. As a wealthy, unmarried landowner she was able to control her own financial and personal affairs including several long-standing lesbian relationships.

The Manchester Observer, 27 November 1819, Copyright the University of Manchester Library

As part of the Peterloo bicentenary, The University of Manchester Library has digitised the entire run of the Manchester Observer which can now be consulted online alongside other Peterloo letters, correspondence, handbills and maps. You can find out more about the John Rylands Library exhibition, ‘Peterloo: Manchester’s Fight for Freedom’ and the bicentenary events here.

On the 11 April 2019 the John Rylands Research Institute will launch a special Peterloo edition of the Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. Tickets for this free event can be booked here. At this event Professor Robert Poole will talk about his detailed research into the Manchester Observer and Dr Katrina Navickas will present her most recent Peterloo research. The Peterloo special edition of the Bulletin of the John Rylands Library (BJRL), including Robert Poole’s, ‘The Manchester Observer: Biography of a Radical Newspaper’, BJRL, 95:1 (spring 2019), 30–122, can be accessed here

0 Comments