Drawing Letters: Ruskin at the Rylands

Dr Luke Uglow, Lecturer in Art History, University of Manchester – held a John Rylands Research Institute pilot grant, summer 2018.

Where to begin when writing about John Ruskin? The great Victorian art critic and social reformer was both precise and cryptic, conservative and progressive, a public figure who was also intensely private. This year, the 200th anniversary of his birth, has been marked by myriad academic conferences and exhibitions, testifying to the breadth and depth of his continuing influence. With subjects ranging from art history to environmentalism, politics to education, there seems to be no topic on which Ruskin did not comment in the over 40 years he was intellectually active. This diversity of activity is beautifully reflected in the Rylands Library’s “John Ruskin Papers”, which contains more than 2000s items, and is an invaluable resource for those wishing to better understand the great Victorian writer.

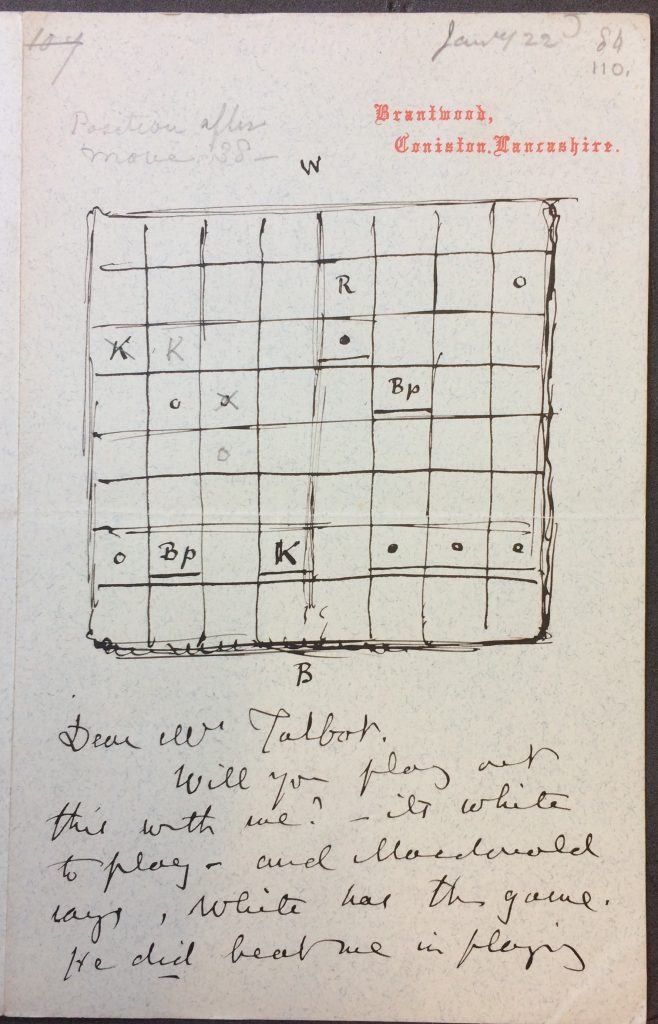

In Summer 2018, in preparation for the Whitworth’s exhibition Joy For Ever (open until 9 June 2019), I worked my way through this material, discovering Ruskin’s love of correspondence chess, his agonising attempts to regenerate society through his Guild of St George, his perpetual hypochondria, and also his voracious appetite for antique books.

Chess Game with Fanny Talbot, 22 January 1884

As an art historian, however, I was a little disappointed. Despite being a prolific letter writer, despite being a talented draughtsman, and despite the crucial role images played in his research and teaching, drawings are notable for their rarity in these epistolary archives. Nevertheless, during my research I did come across some examples of small sketches, nothing that could be considered “Art” in a grand Ruskinian sense, just little instances of visual rhetoric. Many of his letters, and Ruskin wrote a lot of letters, are hastily composed, and so these drawings are doubly interesting in that they register a moment of pause, documenting his giving visual expression to his emotional and intellectual life.

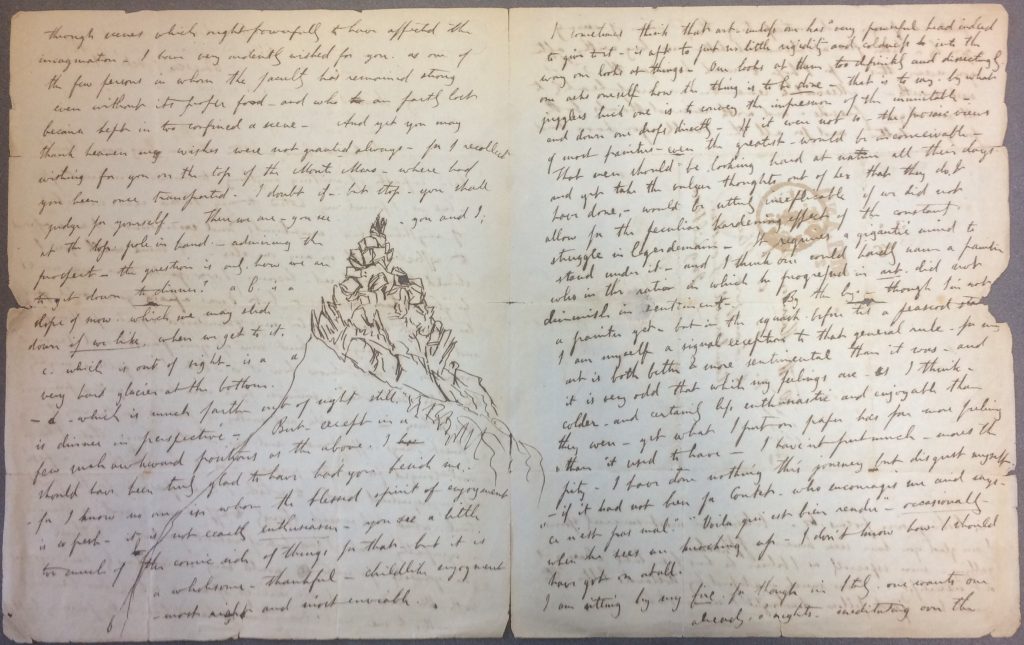

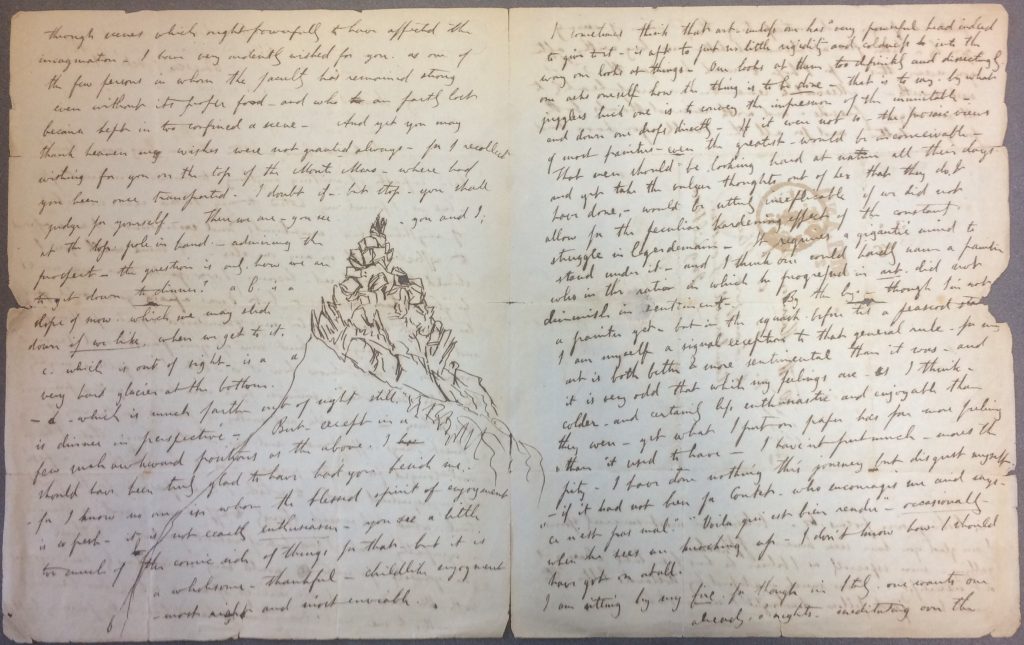

For instance, his letter to William Henry Harrison from Brescia in Italy on 19 October 1845. His tour of the continent in this year was incredibly important both personally and professionally, being the first time the 26 year-old Ruskin had travelled without his parents, and also by providing the material for his second volume of Modern Painters, published in 1846. In this poignant letter to his friend and literary mentor, Ruskin explains how throughout the trip he has longed for a companion who had never been to Italy (like Harrison) “to whom I could present for the first time, what had ceased to strongly affect me, and so recover in sympathy what I had lost in actual pathos”. He continues by recollecting a time, on top of an Alpine peak, that he had wished for his friend to be with him, and to illustrate he offers a little drawing emerging through the text: “There we are – you see – at the top pole in hand admiring the prospect – the question is only, how we are to get down for dinner?”

Ruskin to W. H. Harrison – Brescia, 19 October 1845

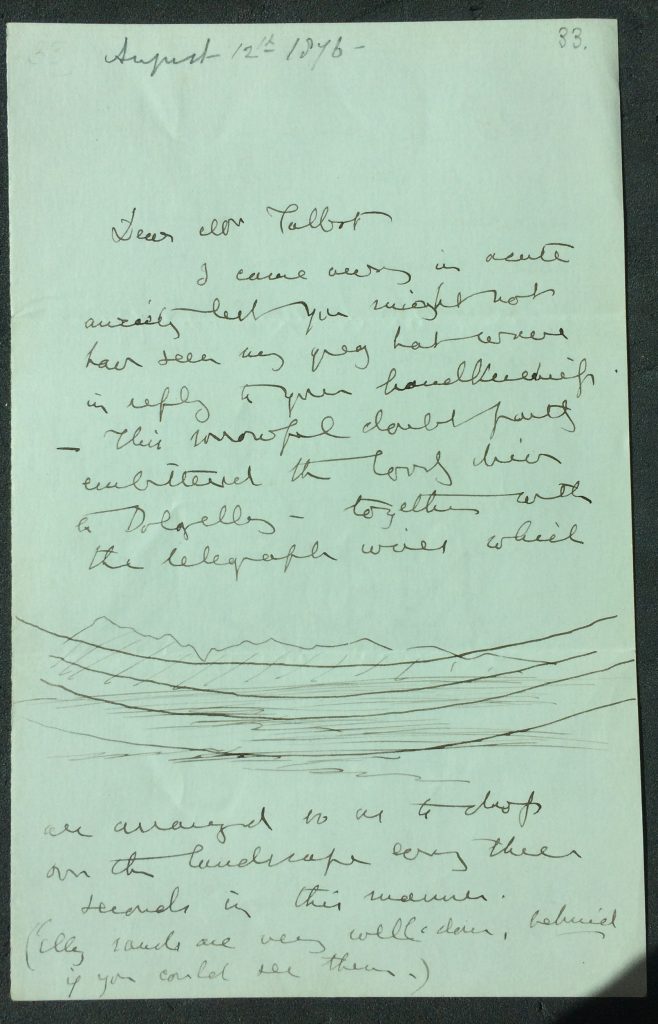

One of the most interesting drawings by Ruskin to be discovered in the Rylands archives dates from 1876. It is a delicate little sketch representing the Afon Mawddach estuary in north Wales. A view over the flat sand to a line of mountains in the distance is interrupted and obscured by four, heavy curving lines – telegraph wires. It was drawn in Oxford after his return, and is a remembrance of the scene from the train between Barmouth and Dolegllau. Ruskin had been to visit Fanny Talbot, a wealthy widow, and her artist son Quartus (Quarry).

The letters between Ruskin and Talbot contained in the Rylands begin in December 1874 when Fanny wrote to offer plots of land and cottages in Barmouth for his St Georges Company (later Guild of St George) – much to Ruskin’s amazement! They continued to correspond and would later in life become good friends. August 1876 was the first time they had met, and Ruskin stayed with the Talbots for 8 days walking along the beaches and inspecting the cottages. In his diary he records their awful state of repair and the extreme poverty of the tenants, which actually made him consider abandoning his project completely.

Ruskin to Fanny Talbot – Oxford, 12 August 1876

In the September 1876 edition of Fors Clavigera he details his visit to Barmouth – yet while commenting on “the noble crystalline rock”, he actually spends more time discussing his train journey down. His particular focus is the awful people he encountered, with their “modern carelessness” and “peculiar cock on a dung hill character of impudence” before ranting about “the desperate, leather-skinned, death-helmeted skull of this wretched England”.

In his 12 August letter to Fanny, he writes: “Dear Mrs Talbot, I came away with acute anxiety lest you might not have seen my grey hat wave in reply to your handkerchief – This sorrowful doubt partly embittered the lovely drive to Dolgelly”. In a different document in the Rylands Library, Talbot herself reminisces about Ruskin’s visit, recalling how on the way to Barmouth he had jumped out of his train carriage and walked the last three miles, struck as he was by the beauty of the landscape. From the train, to his annoyance, this prospect is joined “together with the telegraph wires which are arranged so as to drop over the landscape every three seconds”. We can imagine his frustration. Indeed, the drawing mimics his experience, with the lightly drawn, carefully placed lines covered by these thick, heavily inked wires: “(my sands are very well done behind – if you could see them)”.

Afon Mawddach Estuary

Famously, Ruskin was a critic of industrial capitalism, and from his many diatribes it is easy to construct a view of him as anti-technology, anti-progress, anti-modernity – this drawing only seems to confirm this view. However, on occasion, Ruskin was in favour of technology, but only when it was useful and life-enhancing. Telegraphs are a repeated motif in his writing – there are several mentions in letters in the Rylands – for instance, discussing how he wants to become an ascetic Christian monk living on top of a telegraph pole. Commercial electric telegraphy had been expanding rapidly since the 1840s, with England connected to America via the Atlantic Telegraph in 1866. The line from Britain to India was established in 1870 and so, in the Fors Clavigera of May 1871, Ruskin wrote:

That telegraphic signalling was a discovery; and conceivably, some day, may be a useful one. And there was some excuse for your being a little proud when, about last sixth of April … you knotted a copper wire all the way to Bombay, and flashed a message along it, and back.

But what was the message, and what the answer? Is India the better for what you said to her? Are you the better for what she replied?

If not, you have only wasted an all-round-the-world’s length of copper wire,—which is, indeed, about the sum of your doing.

Clearly Ruskin was impressed by the achievement, but not simply for its own sake – its practical function, its moral implication, is what really mattered. And so, with heavy irony, he goes on to question the value of technological progress (like trains or telegraphs) with no clear purpose: “To talk at a distance, when you have nothing to say, though you were ever so near; to go fast from this place to that, with nothing to do either at one or the other: these are powers certainly.” And it is this, I think, that we see in his drawing for Fanny Talbot of 12 August 1876.

0 Comments