Activist athletes: from a diary about the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo to a livestream with migrant workers in Qatar?

Author: Bram Daanen

“The tournament starts tomorrow for us. A lot is going through my mind.” writes Dutch hockey player Hans Jorritsma (2013) before the opening match at the 1978 Hockey World Cup in Argentina, organised by the murderous dictatorship of Jorge Videla. “Imagine we win a medal… Don’t accept it! I can’t sleep. I take another sleeping pill from the bedside table.” The diary Jorritsma kept at the request of the Dutch weekly magazine Vrij Nederland provides an intriguing insight into both the moral discomfort the championship posed for the athlete and his actions that resulted from it. It shows the results of a campaign against the participation of the national team that ultimately did not achieve its goal but managed to raise great awareness for the cause.

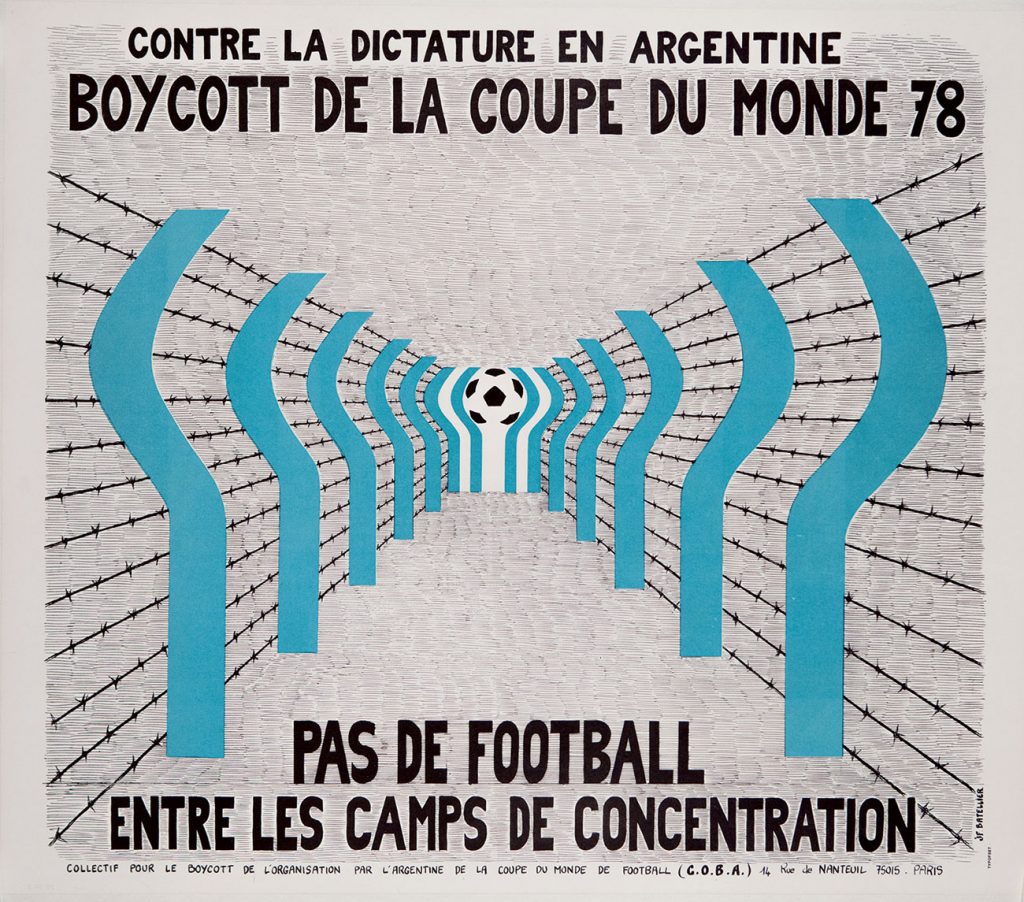

The first exiled Argentines in Europe had been denouncing the violence in their country since 1975, but with the 1978 Football World Cup on the horizon, the attention by Europeans for their efforts suddenly increased. Not only in the Netherlands, but in many European countries, the controversial organisation of this tournament by the Argentinian dictatorship caused public outrage and particularly in France, The Netherlands and Sweden the idea of a boycott gained traction. Although the European idea of a boycott was presented as a form of solidarity, a part of the Argentine exiles opposed it and the idea was unpopular with their family and friends back home. Looking back at the mobilisation in 1978 and its effects can provide us with valuable knowledge about current attempts to instrumentalise mega sporting events. Recently, these endeavours have been dubbed ‘sportswashing’.

Of course, the Argentinian dictatorship’s idea of using sports as a propagandistic tool was not a new one. The classic example of the 1936 Olympics organised by Hitler’s Nazi Germany frequently comes to mind, but as sports historians have pointed out, it would be a mistake to forget the first modern Olympics in 1896 in Greece and the first football World Cup in 1930 in Uruguay as ways to express these countries’ modernity (Tomlinson & Young, 2006) . In fact, it is important to see the instrumentalisation of mega sporting events by authoritarian regimes not as exceptions, but as the rule. Political objectives are inherent to the organisation of such events.

At the same time, it is also important to consider that these attempts do not always work out as planned. The undertaking by the Argentinian regime to instrumentalise the 1978 World Cup has long been considered successful since – despite the mobilisation for a boycott – the tournament took place without any disruptions and the Argentinian victory brought its people together. However, looking at it from an international perspective casts doubt on this affirmation. Before the World Cup, the voices of Argentine exiles in Europe were barely heard at a time when the solidarity movement for Chile dominated the public debate. Without the World Cup bringing the country into the spotlight, the attention for the repression in Argentina would not have reached the levels it did (Daanen, 2022). Two years later, the failure of a similar attempt to instrumentalise a footballing event was even more clear as during the final of the 1980 Mundialito (World Champions’ Gold Cup) organised by the dictatorship in Uruguay, the fans started celebrating the end of the regime (“Se va a acabar, se va a acabar, la dictadura militar”, “it will end, it will end, the military dictatorship”).

Today, with only a couple of months to go until the World Cup in Qatar where the appalling conditions for construction workers have led to thousands of deaths, the footballing world has justified its participation in the tournament with the slogan ‘Football Supports Change’. Hence, it is interesting to look at the ways in which athletes can actually play a role. In 1978, the beforementioned Jorritsma visited the march of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo who became the most emblematic actor in confronting the dictatorship to reclaim their disappeared children and managed to evoke great international attention for their struggle. In his diary, Jorritsma writes:

“After some initial doubts, I approach a group. The fact that I don’t speak Spanish is an obstacle. A mother who speaks English is brought. I explain what is happening in Europe concerning Argentina. I tell them I heard about their silent march. It does them good. The women take turns telling how many children they are missing, how long they have been missing, how many times they have tried to get the executive branch to acknowledge that their child is being held captive. So far without result. There are tears. The women support each other. Some of them grab my forearm during their story. I feel powerless. Sadness takes over.”

Gorini’s (2017) book about the story of the Mothers shows that the opportunity to speak with a Dutch athlete during the Hockey World Cup in February reinforced their belief that they could use the Football World Cup in June to inform the world about what was happening in Argentina. The genuine gesture of an athlete who just listened and took note of the voices of the relatives of the disappeared proved to be an important signal of hope for them. In the midst of debates about whether or not to opt for a boycott it is necessary to take those voices into account and avoid turning the question into a debate on the national conscience. Besides, denunciations in Europe should not be directed just at Qatar, as the officials of European Football Associations have also been responsible for allocating the organisation of the tournament to this country.

So far, no movement for a boycott of Qatar 2022 has managed to gain the same level of attention as the boycott movements in 1978, even if polls have shown that over half of the people across major European nations support such a possibility (Becerra González, 2022) . Paradoxically, when Dutch activists in 1978 managed to evoke great public interest with petition campaigns, press conferences, interviews, and performances of a theatre play, 70% of the Dutch population opposed their idea of a boycott (Baud, 2001) . Even with more public support for a possible boycott, it seems to be receiving less attention.

Finally, with regards to the current debate, prominent Human Rights organisations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have not joined the call for a boycott, and it looks like no boycott will take place. They have argued that the attention generated by the World Cup can support them in their efforts to pressure for improvements of the situation of migrant workers in Qatar. Yet, if the football community really wants to make clear it supports change, it should do more than holding up banners. Wouldn’t it be great to see Messi, Ronaldo or Mbappé (or any other player) take Jorritsma’s idea to the 21st century with a livestreamed visit to construction workers in Qatar?

Short Bio

Bram Daanen is a PhD student in Latin American History at the Freie Universität Berlin and a member of the International Research Training Group ‘Temporalities of Future.’ His thesis focusses on the anticipations and aspirations of the Argentine exile in Europe. Furthermore, he is interested in the interactions between Argentine exiles and European activists, particularly around the 1978 Football World Cup. In a broader sense, his research interests include the exiles of other South American dictatorships at the end of the twentieth century, the Mundialito of 1980, and the history of football.

Bram Daanen is a PhD student in Latin American History at the Freie Universität Berlin and a member of the International Research Training Group ‘Temporalities of Future.’ His thesis focusses on the anticipations and aspirations of the Argentine exile in Europe. Furthermore, he is interested in the interactions between Argentine exiles and European activists, particularly around the 1978 Football World Cup. In a broader sense, his research interests include the exiles of other South American dictatorships at the end of the twentieth century, the Mundialito of 1980, and the history of football.

Contact: bram.daanen@fu-berlin.de

Bibliography

Baud, M. (2001). Militair geweld, burgerlijke verantwoordelijkheid: Argentijnse en Nederlandse perspectieven op het militaire bewind in Argentinië (1976-1983). Sdu Uitgevers.

Becerra González, A. (2022, February 9). Eurotrack: Should countries boycott international sporting events? YouGov Website. https://yougov.co.uk/topics/sport/articles-reports/2022/02/09/eurotrack-should-countries-boycott-international-s

Daanen, B. (2022). Football, dictatorship, and human rights: The 1978 World Cup and solidarity activism in the Netherlands for Argentina. Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights. https://doi.org/10.1177/09240519221112555

Gorini, U. (2017). La rebelión de las Madres: Historia de las Madres de Plaza de Mayo (1976-1983). Editorial de la Universidad Nacional de La Plata.

Jorritsma, H. (2013, December 10). Waarom Hans Jorritsma de zilveren WK-medaille van Videla niet wilde [Newspaper Article]. Vrij Nederland. https://www.vn.nl/waarom-hans-jorritsma-de-zilveren-wk-medaille-van-videla-niet-wilde/?pid=496351

Tomlinson, A., & Young, C. (2006). National identity and global sports events: Culture, politics, and

spectacle in the Olympics and the football world cup. State University of New York Press.

Image credits

Title: événement politique

Date: 1978

Author: Jean-François Batellier

Permission: this file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

0 Comments