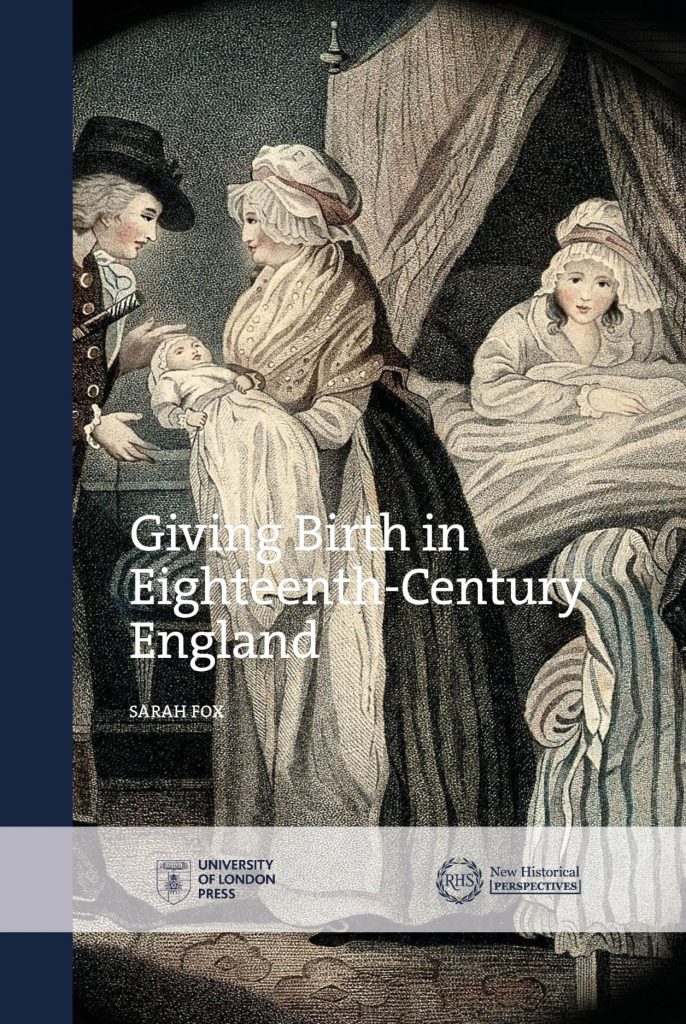

Sarah Fox on Giving Birth in Eighteenth-Century England

This is a guest blog entry by Sarah Fox (University of Birmingham)

My PhD thesis and my book Giving Birth in Eighteenth-Century England both open with the same quote, from a heavily pregnant Betsy Ramsden, the wife of a Surrey schoolmaster and clergyman. Betsy wrote to her cousin Elizabeth Shackleton in Lancashire in 1767 that

I am determin’d not to stay at home any longer till I take to my bed … I give it out to my friends that I shall not give caudle [birth] till the first week in Febry but they say it is impossible I should waddle about till that time I am such a monster in size and indeed I am under great apprehensions I shall drop to pieces before I am ready for the little stranger’

This quote really encapsulates the central themes of the book. The physicality of Betsy’s description of her waddling gait, her monstrous size; the hints at conversations with her friends speculating about the birth itself and the sociability of sharing caudle; and her apprehensions around her lack of preparation all describe an experience of birthing that is largely absent from the narratives of the midwifery texts that have dominated the history of eighteenth-century birth. This book attempts to recover the birthing experiences of women like Betsy Ramsden using their own voices, though this has not always been feasible. Their voices are therefore supplemented by those of their husbands, neighbours, parish officials and medical practitioners through a wide range of sources such as letters and lifewritings, recipe books, folklore traditions, medical textbooks, and court records.

The central premise of the book is that across the eighteenth-century birthing was a process – a series of flexible and linked stages – rather than an event. Childbirth, at least from the mother’s perspective, was characterised by these stages rather than by the delivery that so interested the men-midwives of the period. Throughout the book, I use the term ‘birthing’ to describe an elongated timeframe of up to six weeks, encompassing late pregnancy, labour, and the subsequent month of rest and recovery known as ‘lying-in’. This shift in perspective, to more closely mirror the experiences of the women and men that I study, allows me to make two important interventions in the histories of birthing and midwifery. Firstly, it challenges narratives of the rapid professionalisation of childbirth in this period by revealing a high degree of continuity in traditional birthing practices. Much of my research is focused on the second half of the eighteenth-century; a period when understandings of the body, and of how to treat it, were in transition. This is most evident not during delivery, when you might expect to see ‘modern’ medicine being practiced, but in the arguments about an infant’s first feed, and the advice to nursing mothers. By juxtaposing women’s advice in female-attributed manuscript texts, and their accounts of the early stages of motherhood in their letters with the advice of physicians and men-midwives, we can see both continuity of practice, and change. My focus on the female body therefore disrupts the narrative of Enlightenment progress, of professionalisation and medicalisation that is seen through the publications of the newly prominent man-midwife. It shows that traditional midwives remained consistent and authoritative figures in birthing chambers whose haptic knowledge held its value far beyond the end of the century.

My approach also reveals the rich networks of family, friends, and neighbours that were crucial to the management of birthing in eighteenth-century England. Chapters on household, food, family, and neighbourhood highlight the central role of birthing to the creation of community and in the operation of eighteenth-century society more broadly. Place, space, and locality are important themes throughout the book. I describe the significance of the household, not just as the space in which birth happened, but as an affective space, and as a significant associational space, exploring the intimate relationships between the family, the household, and the neighbourhood. These relationships were defined by locality, which dictated who might be present at the birth, the family members that visited, and the nature of midwifery care. Locality also inscribed itself on the body through the nature and environment of local work and employment, the food that was available, and the drink that celebrated the birth. Looking at birthing from a social perspective, I conclude, allows us to see this essential and regular part of eighteenth-century life as both indicative of, and central to, epistemological and social change.

The book owes a huge debt of gratitude to the Bodies, Emotion and Material Culture Collective through the rigorous PhD supervision of Hannah Barker and Sasha Handley, and from the support and friendship of several Collective researchers. Giving Birth in Eighteenth-Century England is available open access at https://www.sas.ac.uk/publications/giving-birth-eighteenth-century-england. Should you wish to purchase a hard copy, a 30% discount is available using the code SFOXB30.

A Man Mid Wife : A “man-midwife” (male obstetrician) represented by a figure divided in half, one half representing a man and the other a woman. Coloured etching by I. Cruikshank, 1793.Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

Nursemaid : A wealthy Dutch man comforting his wife after giving birth, the child is being fed by a nursemaid. Engraving by P. Tanje, 1757, after C Troost. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark.

0 Comments