The Virginia Venture: An Interview with Misha Ewen

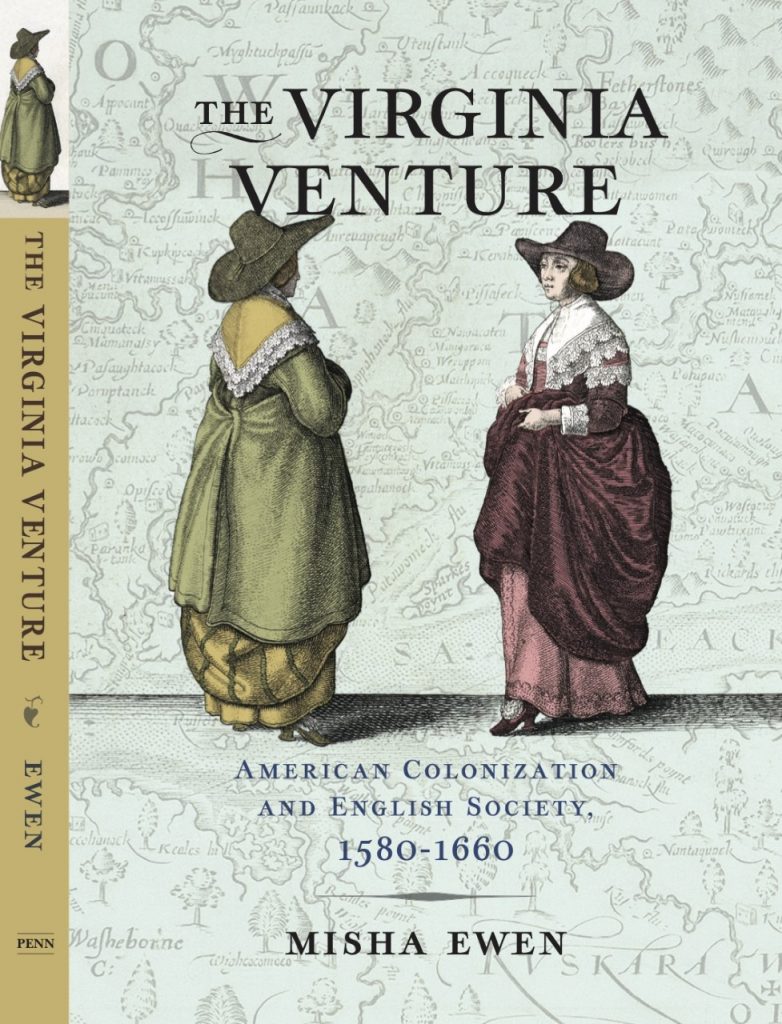

This interview discusses exciting new research by Misha Ewen, a longstanding former member of The Bodies, Emotions and Material Culture Collective. Misha has been the Curator for Inclusive History at Historic Royal Palaces and is just about to start a new position as Lecturer in Early Modern History at the University of Bristol. Her pathbreaking research on gender, colonialism, and trading companies has been published in The Historical Journal, Gender & History, and Cultural and Social History. On the occasion of her newly published monograph The Virginia Venture: American Colonization and English Society, 1580-1660 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022), we invited the author to reply to a few questions.

Stefan Hanß (STH): Misha, warm congratulations to the publication of The Virginia Venture. If you were to introduce your book to readers of this interview, what would you describe as the monograph’s key take-aways?

Misha Ewen (ME): In a nutshell, the book is about how people in England encountered and engaged with colonial activity in Virginia during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. It argues that colonisation was not a singularly elite concern. Instead the colonial project responded to demands ‘from below’ and galvanised support across English society. I think this recognition is important, not only in order to understand the ways that colonisation shaped local concerns and national debates in England, but to appreciate the legacies of colonisation in Britain and the United States today.

Rachel Winchcombe (RW): The historiography to date has been a little dismissive of the idea that many in England were interested in American colonisation projects in the late sixteenth and seventeenth century. Your book brilliantly challenges that notion. When did you first get an inkling that there was more to this story?

ME: I don’t think there was one particular moment, it was a more incremental realisation sharpened by many unexpected encounters in the archive. I was coming across Virginia in court records, in parliamentary debates, and in churchwarden’s accounts. Support for, as well as concerns about, colonisation in Jamestown seemed to reach into many corners of English society. But one example that took me by surprise and spurred me on, and which features in the book’s conclusion, concerns a man accused of theft who told the Justices of the Peace a tale about his recent return from Virginia. It sounds unremarkable, but it struck me that his experience of colonisation was recorded even though it had no obvious relevance to his defence. It was a neat illustration of people’s curiosity about American colonisation, the everyday and personal nature of their encounters with it, and the mark it has left on diverse record sets.

STH: This is one of many fantastic sources discussed in your book. What would you consider the most exciting historical example that you wish to share with the readers of this interview?

ME: I don’t know if readers will find it exciting, but out of curiosity I went to Manchester Central Library (in my hometown, which I had visited countless times before) to see whether there was anything to do with Virginia in the records. I found out that the Virginia Company lottery visited Manchester in 1620, giving local people the opportunity to chance their money (and luck) in the colonial project; in return, the company gave Manchester £30 to put towards charitable purposes. Manchester has a long and complex relationship with empire which clearly did not begin with cotton and industrialisation, and I wondered whether this might have been the first example of institutional support in the city for colonisation. It’s an intriguing idea.

Sasha Handley (SH): What does your book reveal about women’s economic agency in a transnational context that might surprise your readers?

ME: Many readers will be familiar with the role of women in early English overseas colonisation as wives and indentured servants (who do feature in the book), but I think they will be less familiar with the women who never left England, but who pursued colonial interests and profited from it through trade and investment. Only a relatively small number of women bought shares in the Virginia Company, but I explore how many more became entangled with the colonial project through informal investment (including making charitable donations) or by their involvement in plantation, the tobacco trade, or the industries which supported colonisation—everything from providing lodging to colonists in the days before their departure and supplying ships with food. Through their activities I build a picture of how English society, more broadly, was invested in colonisation.

RW: One real strength of your book is your use of the English archive to comment on events and projects taking place across the Atlantic. What other stories might we be able to tell about the extra-English world from these records in future?

ME: I hope that scholars of the seventeenth-century Atlantic world will be inspired to mine local English archives for ‘imperial stories’ relating to other places and projects, because there is certainly untapped potential to surface everyday experiences and understandings of colonisation. During my research into parish, corporation, and quarter sessions records it was not unusual to find other spheres of English colonisation like St Kitts or Newfoundland cropping up, and it would be interesting to see what a close study of those examples might reveal about English attitudes towards colonisation, trade, and slavery in this early period. Now that I’m working on Barbados, I plan to return to local archives for my research.

STH: What was the role of The Bodies, Emotions and Material Culture Collective, or its predecessor Embodied Emotions research group, in the making of this book?

ME: I rewrote most of the book during my time at Manchester, where working alongside and discussing the book with colleagues in the collective helped me to refine my thinking, especially about objects and material culture. I deploy examples in the book, including a purse, a portrait, and a church memorial tablet, to try to understand contemporary attitudes towards colonisation. I do not underestimate how much I was encouraged by colleagues and the research environment at Manchester to pursue this material.

Thank you very much, Misha, and warm congratulations again! This is a marvellous and important book that charts new, exciting research territory! We wish you all the very best in Bristol.

0 Comments