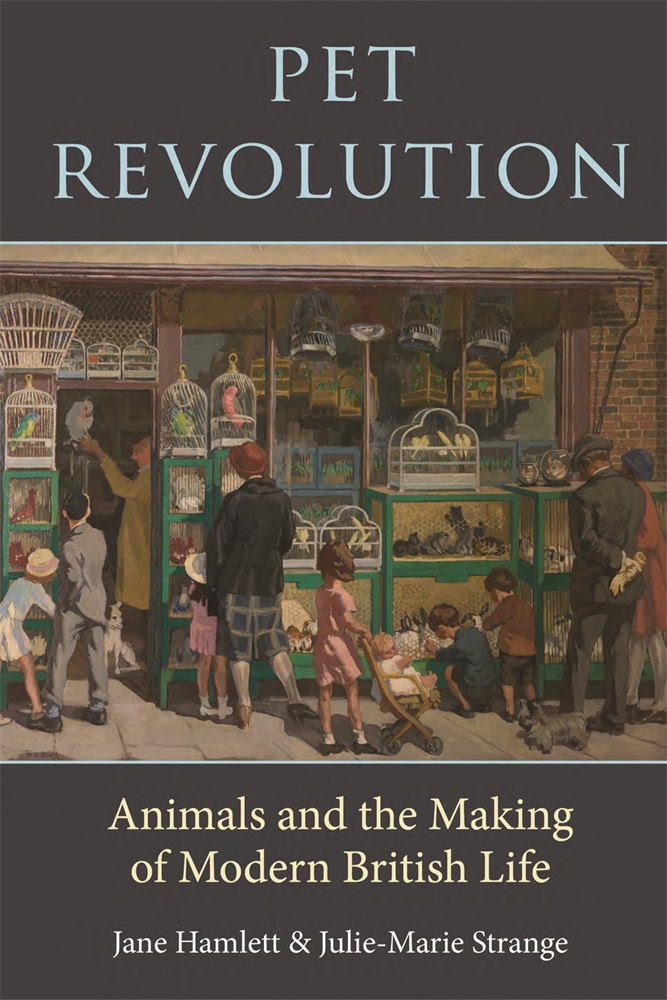

Interview with the Authors of The Pet Revolution: Animals and the Making of Modern British Life (Reaktion Books, 2023)

On the occasion of the publication of The Pet Revolution: Animals and the Making of Modern British Life (Reaktion Books, 2023), co-authored by Jane Hamlett and Julie-Marie Strange, former member of The Bodies, Emotions and Material Culture Collective, Sasha Handley has invited the authors to elaborate on their book.

Hello Julie-Marie and Jane. Many congratulations to you both on the publication of your wonderful new book The Pet Revolution: Animals and the Making of Modern British Life (Reaktion Books, 2023)! The book will interest many members of the Bodies, Emotions and Material Culture Collective, so we are particularly grateful that you have taken time for this interview.

What is the ‘pet revolution’?

Pet Revolution is a cheeky reference to the various ‘revolutions’ that are generally thought to characterise the British nineteenth century: agricultural, industrial, consumer and political. Scholars believe these revolutions made modern Britain. They are entirely human-centric. The Pet Revolution stakes a claim for the importance of animals in shaping modern British life. During the nineteenth century, humans invited animals into their homes on an unprecedented scale; they produced advice books on how best to care for them; and developed a huge array of material consumer goods and services, including medicines, to make human-animal relationships as comfortable as possible. The Pet Revolution depended on the belief that humans had emotional relationships with animals, that animals were affective beings, and that pets made home and family.

The Pet Revolution is a deeply moving book that names the following pets in its acknowledgements ‘Horror Teeth, Kim, Kelley, Pepper (Best Beloved), Maude, Percy, Ronz [and] Bernard’. How far have your own relationships with pets inspired the writing of this book?

We both live with animals and share a deep appreciation of the joy and heartache that loving animals brings. We’re aware first hand that animals make enormous, positive contributions to human wellbeing and we’re both concerned that humans take their responsibility to animals seriously in return. The book takes seriously the intimacy between humans and animals, from falling in love to the pain of loss and bereavement. Is studying intimacy a more intimate kind of research experience?

Here, it was. Pepper died during the project and Julie-Marie could not (still) read first person accounts of pet death, or write about it, without weeping too. Jane found studying animal life a different kind of emotional experience to researching and writing about humans – there’s less emotional distance and she found difficult animal histories (pets were often subject to cruelty) more triggering than difficult human histories. Jane isn’t sure quite why this is apart from the fact that her response to animals in the past is clearly shaped by her relationships with them in the present – relationships based on physical and tactile everyday experiences and interactions that she has had since childhood that have different qualities to human-human relationships.

The book also explores the unique intimacy we have with animals, where caring is paramount. This can generate popular assumptions that companion animals represent ‘substitute’ children. But our book shows how intimacies with animals are significantly more complex than this. Notably, many humans over the past two hundred years have understood their intimacy with animals to be reciprocal: animals care for them too. And for some humans, the unique qualities of animals are what make intimacy possible. For instance, the book references the naturalist Chris Packham’s reflections on how, in the context of living with autism, intimacy with animals can be easier to navigate than that with other humans.

The Pet Revolution includes fascinating insights about how colonialism shaped conceptions of, and relationships with, domestic animals, but how distinctive is the British story of pet-human relationships that you trace?

So, colonialism is important to understanding the trading routes and market availability of some animals, typically identified as ‘exotic’ in a domestic context. But far more important is how the British framed their relationship with nature, the environment and animals through an imperial imaginary that legitimated taking and taming natural resources. This was common in many western countries that sought to justify colonial expansion. Nevertheless, human-animal relations are often intrinsic to the specificities of national identity. British animal organisations have long claimed exceptionalism in relation to British sensibilities about animals; the bulldog was first associated with John Bull in the nineteenth century; stereotypes about Britons’ sentimentality about their dogs were in circulation across Europe from at least the early nineteenth century. Certainly, Britain was the first country in the west to formally establish a number of animal welfare organisations, notably the RSPCA (established 1824). Many of the models of animal welfare and legislation apparently pioneered in Britain were rapidly adopted and adapted by other countries. But if we look beyond Britain now, we see that countries like Roumania have higher rates of dog ownership per household (pre-covid) than the UK. So while the idea of Britain as a nation of pet lovers is often worked into narratives of British exceptionalism, this isn’t really a true picture in numerical terms. What remains particular are the meanings invested in animals as symbols and co-citizens.

Did Manchester’s Embodied Emotions research group (now the Bodies, Emotions and Material Culture Collective) influence the book in any way?

Of course! Julie-Marie had been involved with Embodied Emotions from its foundation; Sasha Handley and Jenny Spinks (now Melbourne) were key figures of inspiration. As someone who had worked primarily on a Victorian working-class culture that typically left little textual trace, Julie-Marie benefit enormously from being in dialogue with a specifically early modern scholarship on the history of emotions and material culture that looked to materiality and embodiment as a more creative methodology. Having space and time to discuss these approaches across chronologies and in different geographies is so valuable. Jane had a post-doctoral research fellowship at Manchester in 2007 after studying middle-class domesticity and material culture with Amanda Vickery at Royal Holloway, University of London. We shared an office and realised we had shared interests in emotions and material culture. Pet Revolution is the tangible outcome of that meeting of interests. We hope there will be more!

0 Comments