Food brands cheat customers from Eastern Europe with lower-quality products

by Boris Vysnan

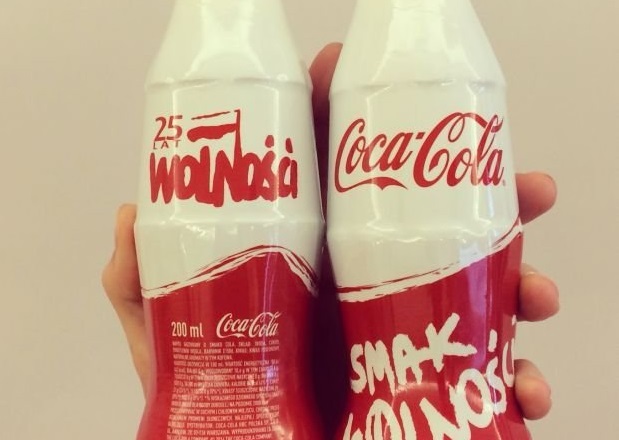

Before the Velvet Revolution and the fall of the Berlin Wall, which was a symbol of separation and isolation of Central and Eastern Europe from the West, a wide variety of international products available at supermarkets to buy was something unknown (or poorly reproduced at best) to shoppers from countries like Hungary, Poland or the Czech Republic. After the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, when the international market was finally introduced to the countries of the former Eastern Bloc it seemed that those distribution differences were no longer present. Shoppers were now able to buy the same Nestle or Coca-Cola products in a convenience store in Prague that they could buy in a similar shop in London or Berlin.Or so it seemed.

In reality, people living on the east side of Czech-German borders (or Hungarian-Austrian borders) are often willing to cross them just to buy food of better quality, but of the same brand. Meanwhile, shops such as Müller, a German chain, do a roaring business in those countries and elsewhere – in part, it is said, because they sell brands produced in western factories, rather than those produced closer to home. Multinational food and drink companies have “cheated and misled” shoppers in eastern Europe for years by selling them inferior versions of well-known brands, according to the European commission’s most senior official responsible for justice and consumers. According to Jourova, the eastern versions of brands sold across Europe, from fruit drinks and fish fingers to detergents and chocolate have repeatedly been found to be inferior in quality to those sold in the west, even when they are wrapped in exactly the same branding.

In an attempt to provide conclusive evidence of longstanding differences in food quality between similarly branded products in east and west Europe, five countries – Slovenia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Slovakia and the Czech Republic – have carried out extensive comparative tests on different products, such as Coca-Cola, Bird’s Eye fish fingers or Persil. The findings were surprising – or not so much for consumers of those countries. A bottle of coke purchased in Slovenia contained 11.2 % of sugar compared to 10.5% in one bought in Austria. Fish fingers contained 58% of fish meat in Slovakia compared to 65% in Austria and Persil liquid detergent in the Czech Republic had less of an active ingredient than in Germany.

This was the official statement about the food duality in the East European market, issued by Florence Ranson who is a spokeswoman for FoodDrink Europe; the representative group for the industry. “We are active proponents of the single market and the free circulation of goods in particular. Within this frame, it is normal practice that manufacturers source ingredients locally and adapt to local tastes. It must also be stressed that whatever the recipe, our food always meets European standards and remains the safest in the world. The companies currently in the spotlight have rigorous quality management systems in place to ensure consistent quality across their brands all over the world.”

However, a claim that ingredients are adapted to a local taste is infuriating for local consumers as the production is often based in Western Europe and with findings of different food quality it directly implies that Eastern Europe is a food dumpster of the union. In some cases, the issue goes even beyond consumers being misled, even putting their health at risk. High levels of dangerous industrial trans fats contained in hydrogenated vegetable oils were a reason for a volunteering reduction of their use by manufacturers in Western Europe. According to the World Health Organisation, as little as 5g per day is associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease. In Eastern Europe, in contrast, they are still commonly present in the products. According to a 2012 food analysis, Eastern Europeans could be consuming as much as 30g a day.

Wages remain divergent in the EU – with the GDP represented by wages on average 7% lower in central and eastern European countries than in the west. However, the price difference of the same product in Western markets is often much smaller than 7 %. It is quite clear that the reason for those unacceptable practices is to gain more profit, even if it negotiates quality and health standards. This unfair commercial practice is a sign of ongoing inequality within Europe and poses the moral question of whether people in Eastern Europe don’t deserve the same quality of food and products as people in Western Europe.

References

Boffey, D. (2017). Europe’s ‘food apartheid’: are brands in the east lower quality than in the west? 15 September 2017. The Guardian, (Accessed: 07 March 2018).

Boffey, D. (2017). Food brands ‘cheat’ eastern European shoppers with inferior products. 15 September 21 2017. The Guardian, (Accessed: 07 March 2018).

MacGuil, A (2017). In eastern Europe, we don’t prefer to eat garbage’: readers on food inequality. 21 September 2017. The Guardian, (Accessed: 08 March 2018).

Michail, N. (2016). Multinational firms sell poorer quality (but more expensive) food to Eastern Europeans. Available online., (Accessed: 08 March 2018).

0 Comments