Early Career Research Fellow: Michael Smith

Michael Smith is an Early Career Researcher who works on the history of emotions and religious culture in the early modern period. During summer 2018, Michael held an Early Career Fellowship at the John Rylands Research Institute, and his project was focused on devotional affections in the John Rylands Library Collection. Here he talks about his experiences at the JRRI and how the fellowship has helped him to develop a larger postdoctoral project.

I was lucky enough to receive a three month Early Career Researcher (ECR) Fellowship with the John Rylands Research Institute (JRRI) in June. I used the time to work on my postdoctoral project, ‘Affect and Affections in English Protestantism, c.1649-c.1745’. I already had some familiarity with the collections having read for my PhD at Manchester but this was a great opportunity to explore them further and particularly get to grips with the Methodist collections.

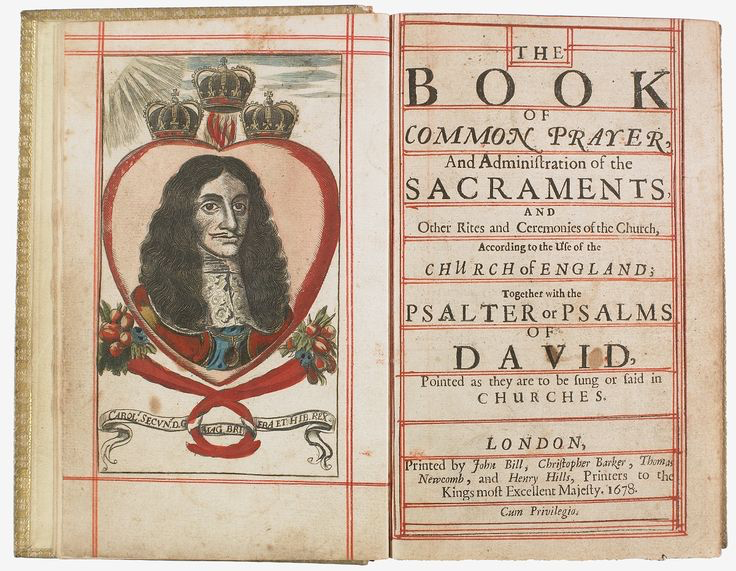

My doctoral thesis read emotions back into the Protestant religious cultures of Restoration and Augustan England.[1] Scholarship has often downplayed the emotional aspect of faith in the period. Most recently, scholars have suggested that social utility was the motivating ideology of the period’s religious cultures.[2] In addition, the vigour of Church of England and dissenting religiosity in the period has been unfavourably compared in the historiography with that of Methodism and the Evangelical Revival, which emerged from the 1730s. In contrast my research found feeling to be central to the lives of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Protestants, both conforming and nonconforming.

The new project looks to build upon this foundation. It will provide a model for the role emotions played in the religious lives of Protestants between the execution of Charles I and the end of the Jacobite threat. One of the interesting discoveries of my doctoral research that I am looking to develop is the way in which Protestants of all parties sought to manage their emotions. This was not motivated by a stoic desire to supress displays of religious fervour. In fact, a range of emotions were embraced by these early modern men and women as part of their devotional practice. Without them, they frequently recorded religious duty as improperly performed. It seems also to have had a broader significance, helping them to balance their mood and achieve an overall godly disposition.

These preoccupations can be seen within the life-writings in the Rylands’ collections. One such example is Richard Viney’s, a sometime Moravian and contemporary of John Wesley’s, methodical diary. His entries for each day were structured around the headings ‘Employ’, ‘Mind’, ‘Health’, ‘Weather’ and ‘Occurrences’. His record of his ‘mind’, in particular, was dominated with accounts of his emotional state and demonstrated his desire to monitor, and manage, his feelings as part of his spiritual life. The entries of his diary often followed a similar pattern to that which I observed during my PhD research. Personal duties were dominated by confessional self-reproach, while public duties by joy and comfort in hearing the word of God and sharing in his sacrifice.

On Saturday 8 January 1744 Viney bemoaned having ‘spent this day to little profit, and indeed have many days and weeks. May ye lord forgive me all my Faults’. The next day, however, he recorded that his ‘Mind [was] more compos’d and … easy. At Smithouse I was very cheerful and glad of an opportunity of speaking something of our saviour.’[1] Viney’s spat with his Moravian congregation, and his subsequent denominational homelessness, certainly influenced his account. Yet, it also demonstrated the way in which different emotional states were attached to different devotional practices. This entry showed how devotional practice was an exercise in feeling and managing feeling. Public worship both contributed to, and was defined by, his cheerfulness. By listening to a sermon, with its attendant affective high, he balanced out his low mood from the previous day.

These findings in the Rylands’ collection offer the promise of further continuities to be found within the role of emotions in Protestant religious culture between 1649 and 1745. The close association between feeling and faith can be witnessed in these accounts. Moreover, they show how feeling was managed and measured by these Protestants. The employment of different emotions at different times paralleled the balance they sought in bodily health. The body itself was often presented as the arena on which they managed their devotional affections. It is this parallel that I am increasingly interested in providing a model for in my new project.

For more information about the funding opportunities available to Early Career Researchers, keep an eye on our website or follow us on Twitter.

[1] Smith House was the location of a Moravian congregation in Halifax; JRULSC, Moravian Chruch Manuscripts, GB 133 Eng MS 965, Diary of Richard Viney, p.7

[1] Michael A. L. Smith, ‘The Affective Communities of Protestantism in North West England, c.1660-c.1740’, Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Manchester, (2017).

[2] Brent Sirota, The Christian Monitors: The Church of England and the Age of Benevolence, 1680-1730 (London, 2014); William J. Bulman, Anglican Enlightenment: Orientalism, Religion and Politics in England and its Empire, 1648-1715 (Cambridge, 2015)

0 Comments