Ageing society in Japan and its political influences

by Sumire Ebara

The global population has been rapidly ageing. The reason behind this phenomenon is the shift from the combination of high birth rates and death rates to that of low birth rates and death rates because of the considerable improvements in health care for pregnant women, medical care, education about nutrition and hygiene and healthier lifestyles as Timonen proposes in his ethnography (2008, pp.14).

Timonen also argues that population ageing is happening across the globe at different paces and in different patterns. In developing countries, the issue of ageing societies has emerged relatively recently, and the speed is much faster than that seen in developed countries. For those countries, the challenges are to improve their infrastructure to catch up with the pace of the population’s ageing and to support the old age groups (2008, pp.13-27). Researchers estimate that the developing world is going to face the fastest speed of ageing, however. At this moment, the oldest and fastest ageing country in the world is Japan: the country with the longest life expectancy and the highest percentage of elderly people out of the whole population.

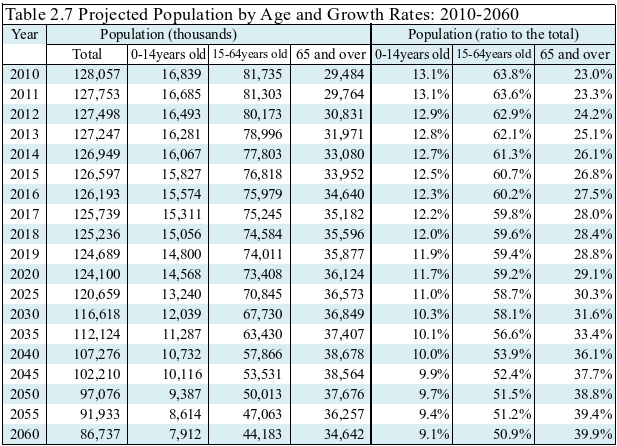

As a young Japanese woman, I would like to discuss the ageing society in Japan with focus on its political ramifications. The latest figures show that Japan’s population has reached a total of 126,903,000, of which 27.2% are aged 65 or over, while those younger than 14 years old are just 12.4% (Statistics of Population, 2017). The percentage of senior citizens has been increasing ever since the postwar period when the country made tremendous progress in many fields including medical research, which has led to an improvement in the population’s longevity. Likewise, it is estimated that the number of people aged 65 or above will continue to grow. As shown in Table 2.7, Japan’s population as a whole will soon start to shrink, while the proportion of the old will not stop to expand. Consequently, by 2060 the population will decline by 30% and almost 40% will be comprised of the old.

The biggest concern here is the effect that the increasing number of old people will have on society. According to Harney (2013), in order to sustain the strength of the country’s economy as well as the stability of its political system and to rescue future generations from possible disaster, there are three obstacles that Japan has to overcome: politically uninvolved young citizens, the elderly-friendly election system and the costly national health care and pension system.

Japan’s Ageing Population – Source: National Institute of Population and Social Security Research

These three issues are interrelated. Although the government last year finally lowered the voting age from 20 years to 18, thus adding 200,000 young Japanese to the electorate, the youth’s influence on politics is still insignificant. This is because they are not yet concerned with politics, and they are not well-educated enough to be confident of their political assessment. At the same time, the policies that most politicians publicly pursue are consistently focused on social welfare that primarily benefits elderly people, which makes them not very appealing to young voters. Moreover, politicians propose better arrangements for medical care in order to win an election by attracting old people who hold a much greater proportion of votes compared to that of young people. Also, the average age of the cabinet members in Japan is 61 years, so it is no wonder that policymakers listen to the voices of the elderly rather than those of the youth. Finally, because both the senior citizens and policymakers are desperate to keep their political benefits from social welfare and ignore what would happen to the future generations, the government ends up spending too much on maintaining the national health care program and pension system. Ironically, the elderly people have gone through the peak of Japanese economy and have earned much more than today’s working-age citizens, but they definitely receive more pension benefits than the young will in their future. This is why I loathe the obligation to have to make payments to the national pension plan. Furthermore, when it is undoubtedly tough for young adults to financially assure their own stable future, who would like to get married and raise their children in such a country like Japan? Therefore, the challenges to the Japanese government is to make having family affordable as well as dealing with the reality of an ageing society. Still, the immediate challenge to developed countries like Japan remains in making being old more affordable (Timonen, 2008, pp. 27). And yet, this continues to be morally essential no matter how much I detest the government’s prioritization of the care for the elderly people over the younger.

References

Harney, A. (2013). Japan’s Silver Democracy.

‘Statistics of Population: Definitive Value in September 2016’ (2017). Statistics Bureau.

Timonen, V. (2008). Demography 101: Why Do Populations Age? In Ageing Societies: A Comparative Introduction. Open University Press, pp. 13–27.

0 Comments