Does academic debate on ‘radicalisation’ increase or decrease the threat of violent extremism?

Blog by Lydia Wilson

Radicalisation refers to a process of which the outcome is not radicalism but violent extremism. Violent extremism “describes a situation in which extreme belief in a social, political or ideological cause is coupled with the belief that violence is necessary and justified (…) to further that cause”. The academic debate surrounding radicalisation and violent extremism has shifted dramatically from the 1970s where it was used to understand structures and behaviours of violent groups compared to the 21st Century where radicalisation is closely associated with Islamist terrorism. However, how has this shift affected the individual understanding of what violent extremism is? I will consider how academic debate surrounding ‘radicalisation’ has either increased or decreased the threat of violent extremism.

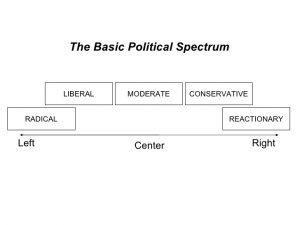

The basic political spectrum

So firstly, let us consider what a radical is. A radical can be defined in two ways; in absolute terms and in relative terms, the latter argues that simply radicalism is the opposite of reformism. Talking absolutely, a radical pushes for fundamental change that goes to the heart of society’s systems rather than advocating smaller, incremental changes. Policy makers and governments have varying absolute definitions but concur that a radical is not always a terrorist and governments should only be concerned with radicals and radicalism that pose a threat. On the other hand, radicalism can be considered in relative terms. This situates a person on a continuum of organised opinion, this continuum is not fixed. Schmid (2013), for example, argues that many ‘radical’ demands of the 19th and early 20th century such as women’s right to vote have become obvious entitlements in the 21st century. ‘Radicalisation’ in the UK presents a significant move on the continuum. This continuum can decrease the threat of radicalisation as it allows policymakers to place radicals on this scale and consider the likelihood of those individuals being a threat.

However, considering ‘radicalisation’ on an ever-changing continuum has some key limitations. Firstly, where should the distinction between extreme and moderate radicalism be on this continuum and who should make this continuum, especially when definitions of what a radical is can differ between countries? Sedgwick (2010) supports this view by arguing that academics defining radicalisation in diverse ways can lead to confusion and therefore the misrepresentation of certain groups, which means they are unfairly being excluded from political processes. For example, only 6.6% of members of parliament are non-white. This could increase the threat of terrorism as people with weaker ties to wider society are more susceptible to joining radical groups and consequently engaging in extremist violence. For the reasons provided, Schmid (2013) is eager to make a clear distinction between what society defines as a radical and an extremist. The latter, Schmid (2013) argues, are open- minded and although upholding radical views, accept diversity. These contrast drastically to extremists as they are extremely close minded and seek to use force to implement a rigid society that oppresses minorities. This distinction is particularly helpful as it is recognised and actively used by EC Expert Group on Violent Radicalisation (2006).

To decrease the threat of violent extremism, academics need to establish how people become violent extremists and how individuals are radicalised. “To foster a more in-depth understanding of the psychological processes leading to terrorism” (Moghaddam 2005: 161), Moghaddam (2005) argues that there is a staircase approach to terrorism, he suggests that:

“Although the vast majority of people, even when feeling deprived and unfairly treated, remain on the ground floor, some individuals climb up and are eventually recruited into terrorist organisations.” (2005: 161)

Through creating a step by step guide to how an individual begins to commit acts of terrorism, it decreases the threat of terrorism as it can easily be established where a person is on the spectrum and assess their threat level. However, this is criticised by Doosje et al (2013) who argue that factors that result in radicalisation are extremely complex and varied. It can often combine a range of influencing factors such as an individual’s psychological well-being, demographics, setting, and contact with extremist recruiters. Doosje et al (2013) suggest a more complex model of radicalisation, which combines three significant factors that could predict support for radical belief systems. These are an individual feeling disconnected from society and not trusting existing authoritative bodies, an individual feeling a sense of doubt and instability in world views, and an individual feeling an out of group threat to their own beliefs and cultures, for example, a symbolic threat to Islamic culture.

However, Kundnani (2012) is especially critical of academic debate surrounding radicalisation. Through critical examination, Kundnani (2012) shows how the concept of radicalisation used by industry scholars is limited and biased. He asserts the concept of radicalisation has led to “[…] civil rights abuses and a damaging failure to understand the nature of the political conflicts governments are involved in” (2012: 3). He acknowledges that radicalisation provides a framework to investigate terrorism but is critical as the concept is not objective and is only designed to advantage authoritative groups such as security bodies and the government. Kundnani (2012) argues that academic debate increases the threat of extremist violence as it is limited to the assumptions that:

“[…] those perpetrating terrorist violence are drawn from a larger pool of extremist sympathisers who share an Islamic theology that inspires their actions; that entry into this wider pool of extremists can be predicted by individual or group psychological and theological facts; and that knowledge of these factors could allow government policies that reduce the risk of terrorism” (2012: 5)

This increases the threat of violent extremism as it leads to the construction of Muslim ideologies as ‘suspect’ and dangerous. Thus, it leads to the exclusion of these groups and consequently to the increased chance of them climbing up the ‘staircase of terrorism’ (Moghaddam 2005).

So how does academic debate affect threat levels of extremist violence? Well, it depends on the level of misinterpretation surrounding the process of radicalisation and the effects of the misinterpretation. But it is clear that the risk of extremist violence is rising. The academic debate needs, therefore, to take an objective stance to establish how and why individuals become radicalised in an attempt to decrease the threat of extremist violence against innocent people.

References

Aly, A., n.d. Radicalisation and the lone wolf: what we do and don’t know. The Conversation (accessed 5.23.17).

Record numbers of female and minority-ethnic MPs in new House of Commons | Politics | The Guardian (accessed 5.23.17).

Francis, M., n.d. What we’ve learned about radicalisation since 7/7 bombings a decade ago [WWW Document]. The Conversation. URL (accessed 5.23.17).

Doosje, Bertjan, Annemarie Loseman, and Kees Bos. “Determinants of radicalization of Islamic youth in the Netherlands: Personal uncertainty, perceived injustice, and perceived group threat.” Journal of Social Issues 69.3 (2013): 586-604

Kundnani, A., 2012. Radicalisation: the journey of a concept. Race & Class, 54(2), pp.3-25

Moghaddam, F.M., 2005. The staircase to terrorism: a psychological exploration. American Psychologist, 60(2), p.161.

Schmid, A.P., 2013. Radicalisation, de-radicalisation, counter-radicalisation: A conceptual discussion and literature review. ICCT Research Paper, 97, p.22.

Sedgwick, M., 2010. The concept of radicalization as a source of confusion. Terrorism and Political Violence, 22(4), pp.479-494.

0 Comments