Global Social Challenges in the Wake of the Queen’s Death

Written by Dr Jonathan Davies, Programme Director of BA Global Social Challenges. You can get in touch with Dr Davies on jonathan.davies-4@manchester.ac.uk.

The death of Queen Elizabeth II has focused public and political attention on her life and legacy. It has also uniquely brought up some of the issues and future challenges that will be considered in a new degree programme at Manchester.

In the School of Social Sciences here at Manchester, we are developing a new transdisciplinary degree programme – BA Global Social Challenges. The degree examines globally significant harms from a variety of intellectual perspectives, and it integrates debates and policy experiences from across the world. This blog discusses the death of Queen Elizabeth II and how this event raises some of the concepts and themes that will be a focus for consideration on the course.

The death of a long-serving monarch and the transition to a new head of Kingdom, Commonwealth, and Church is an entry point for conversations about legacies of empire; the global distributions of power, legitimacy, and responsibility (historic and future); consideration of issues of race, ethnicity, identity, and voice; as well as profound constitutional questions about hereditary principles and monarchical authority. Moreover, the Queen’s death is an entry point for reflection on the social, geopolitical, and cultural changes that have occurred during the seventy years of her reign, and the very different world and challenges that King Charles III has inherited.

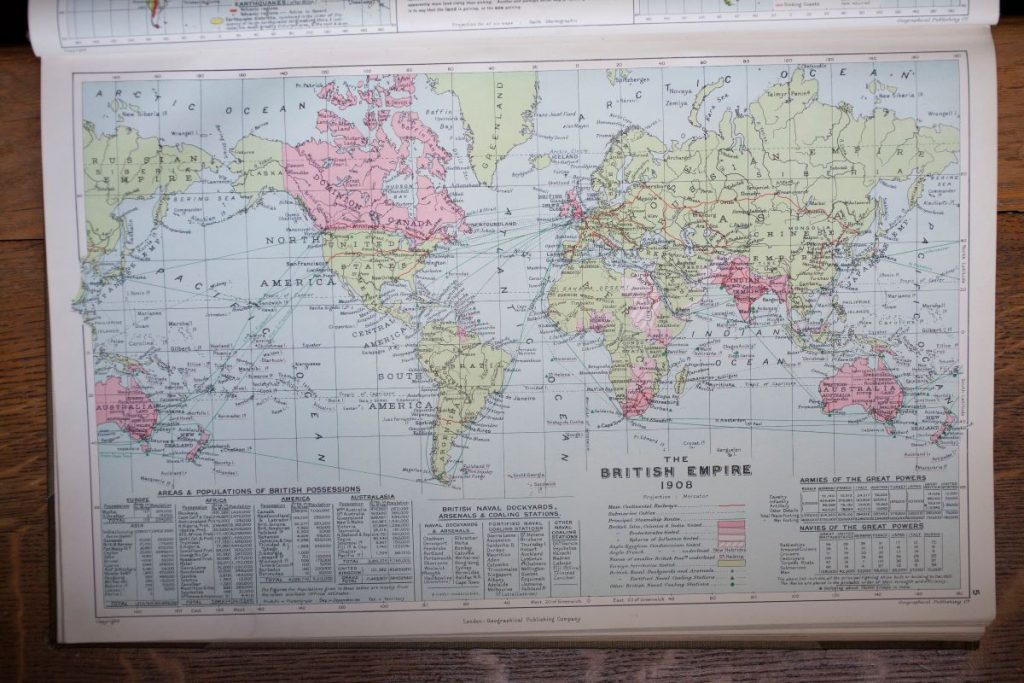

Legacies of empire

Although some may view the British Empire and decolonisation largely in historical terms, its legacy still strongly resonates and is far from resolved. Decolonisation has brought issues of reparation to the forefront of discussion which are likely to remain important political debates of the future, including (but not limited to) the issue of transatlantic slavery. The role of former imperial powers and the decolonisation process relates strongly to the themes of violence and state control that form a key part of the new degree programme.

To take just one example of how decolonisation permeates modern debate, the disputed islands of the Chagos Archipelago illustrates the legacy of how the UK controls overseas territory. In 2019, the International Court of Justice issued a (non-binding) opinion that the UK should “bring to an end its administration of the Chagos Archipelago as rapidly as possible, and that all Member States must co-operate with the United Nations to complete the decolonization of Mauritius”. Some researchers suggest that the UK has even colluded with the US to maintain control over the Archipelago due to the presence of a US Naval Station, thereby making them ‘co-offenders’ from certain perspectives. These discussions on the role of former imperial powers and the decolonisation process are likely to come under increasing scrutiny as the world continues to reflect on political-economic (as well as security and strategic) conditions that have shaped the modern era.

Race, ethnicity, and identity

Turning to related issues of identity, there are various social inequalities and injustices associated with race and ethnicity, which will also form a key theme on the degree. The new UK Home Secretary, Suella Braverman – who herself is of Indian origin through her parents from Kenya and Mauritius, recently stated that she was proud of the British Empire as part of a broader attack on the Left for being ashamed of UK history. Of course, she is not the only person defending aspects of the British Empire and its legacy, but should this really be a source of or motivation for pride out of all the other social issues she could influence?

As immigration policy and border security falls under the Home Office’s remit, the ‘hostile environment’ approach has led to the development of systematic injustices to those mainly from the Global South, with Windrush and more recently the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 being just some examples. In turn, the hostile environment, sometimes linked with broader concerns over racism within the UK, raises serious and long-standing questions about how undocumented migrants are vulnerable to human trafficking and exploitation (but that will have to be a separate post!). Perhaps a global challenge to tease out of these discussions revolves around use of social media and its entrenched/polarised atmosphere with which to conduct these complex debates on identity, immigration, and ethnicity.

Monarchical authority

Closely linked to the themes of injustice and violence highlighted above is how governance – in other words, issues that relate to hierarchy, oversight, and accountability, function in modern democracies. In the UK context, this has recently translated into discussions on what role an unelected figurehead should have in a modern democracy as head of state, especially given the monarchy’s connections with imperialism. Theoretically, the monarchy now has little political ‘power’, yet it retains access to significant resources, wealth, land, as well as connections to elite individuals and institutions that most people in society do not.

Despite these well-known disparities, the monarchy remains generally popular in the UK, and there is little indication that republican movements will gain significant traction to abolish the monarchy any time soon. Perhaps a relevant question to pose as a global challenge, at least in relation to the Commonwealth, is how the monarchy can reproduce its influence and legitimacy under King Charles III – in other words, how should it modernise? This connects with a broader question about the legitimacy of institutions that impact all of us.

Moves towards a serious discussion?

We can signpost these challenges here as questions of ongoing concern, to evaluate the relative opportunities and risks of steps that states need to take to present a democratic and rights-based response to these issues. Surely a more fitting tribute to Elizabeth II and her legacy would be to develop a serious discussion on challenges stemming from the legacies of decolonisation, contemporary identities, and the status of the monarchy as an institution – challenges which still resonate in the modern era.

Perhaps such a discussion would be a preferable alternative and something of a middle ground between unquestioned ‘flag waving’ on the one hand and exaggerated ‘Brit-bashing’ on the other that has taken place in recent weeks. Since political discussion is increasingly polarised, especially via social media, this aspiration may sound fine in principle but could well turn out to be a tall order in practice. Either way, these topics are going to shape debates of the future that we want to position students for, so they will certainly have a place as part of the discussions on BA Global Social Challenges at Manchester.

0 Comments