Causes of food allergy

Our knowledge about the causes of food allergy is still limited. Scientists suspect that environmental factors, including lifestyle and diet, interact with a genetic predisposition to increase the risk of the disease.

Gene-environment interactions were demonstrated in a HealthNuts study of 5,300 children which examined associations between parents’ country of birth and their offspring’s peanut allergy.

The study revealed that peanut allergy was three times more common in Asian infants whose parents were born in East Asia compared to those with parents born in Australia (Koplin et al, 2014).

By increasing our understanding of the mechanism behind allergic reactions, in the future we could improve the management of food allergy, as well as prevent severe and fatal reactions.

The genes of food allergy

Studies undertaken to identify genetic markers associated with food allergy have often been limited by the size of the studies. One susceptibility locus identified for food allergy (called C11orf30) has also been linked to levels of IgE and asthma.

The suspected genes include those coding for proteins involved in the immune response, breakdown of food proteins, and integrity of the barriers (skin and mucous membrane) which protect from the allergen exposure.

Studies of twins suggest that about 80% of the risk for food allergies can be passed from parent to child, but more studies must be carried out to find out more about genetic risk factors.

Digestion of food allergens

The food we eat must be broken down before it can be absorbed and transported around the body to where it is needed. The digestibility of food (cooked foods are more digestible) could determine if food proteins will be tolerated in the body or not.

It has been reported that partially digested food proteins may be recognised by the body as ‘invaders’ and an allergic response will likely develop. Therefore, individuals with reduced stomach acidity (due to medication, stress, vitamin B and zinc deficiency) may be at higher risk of developing food allergy or of aggravation of existing food allergy symptoms.

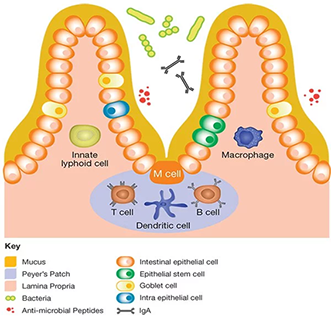

The gut immune system

Cells of the immune system are distributed all over our body; however, the highest number surrounds our gut, which is inhabited by trillions of microorganisms known as microbiota.

Research suggests that microbiota is involved in a range of useful functions such as teaching the gut immune system to recognise foods as harmless. Not surprisingly, any changes in the gut microbiome (e.g. caused by antibiotics) will negatively affect immune tolerance mechanisms and as a result play a significant role in the development of food allergy or aggravation of allergic symptoms.

This is supported by a study which found that allergic and non-allergic infants had different composition of bacteria in their guts.

Scientists suggest that making our diet more microbiome-friendly, by consuming more probiotics and prebiotics, could help in the management or even prevention of food allergies (Cannani et al. 2019). However, more research is needed to confirm these suggestions.

The role of nutrients

It has been suggested that some nutrients may contribute to the development of food allergy:

- Vitamin D is an important regulator of immune response. Scientists have proposed that both excess and low levels of vitamin D in the body, which are regulated by the sun exposure and dietary intake of the vitamin, may increase the risk of food allergy.

- Omega-3 fatty acids regulate immune response and have anti-inflammatory effect protecting the cells from damage. Evidence suggests that omega-3 fatty acids intake has decreased and omega-6 fatty acids intake has increased from ancestral times. This imbalance leads to increased inflammation in the body and can potentially increase the risk of food allergies.

- Folate has been shown to affect immune function, so concerns have been raised on whether taking folate supplements during pregnancy and/or early childhood can increase the risk of developing food allergies. The scientific evidence to confirm this association is lacking and more studies need to be undertaken.

- Other nutrients. It has been reported that maternal diet rich in foods containing antioxidants (vitamin C and copper) lowered the risk of developing food allergy in infants. Interestingly, vitamin and mineral supplementation may not have the same protective effect.

Further reading

- Canani, R.B., Paparo, L., Nocerino, R., et al. (2019) Gut Microbiome as Target for Innovative Strategies Against Food Allergy

- Zhao,W., Ho, H.E., Bunyavanich, S (2019) The gut microbiome in food allergy

- Singh, R. K., Chang, H. W., Yan, D., Lee, K. M., Ucmak, D., Wong, K., Liao, W. (2017) Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health

- Tan, J., McKenzie, C., Vuillermin, P.J., et al. (2016) Dietary fiber and bacterial SCFA enhance oral tolerance and protect against food allergy through diverse cellular pathways

- Koplin, J.J., Peters, R.L., Ponsonby, A.L., et al. (2014) Increased risk of peanut allergy in infants of Asian-born parents compared to those of Australian-born parents

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (2016) Potential Genetic and Environmental Determinants of Food Allergy Risk and Possible Prevention Strategies

- Lack, G (2008) Epidemiological risks for food allergy- dual allergen-exposure hyposthesis