Knife crime: why prison isn’t the answer

by Ella O’Doherty

Knife crime has been headlining UK news for weeks now, with rates soaring across the country. Many politicians, media outlets, and much of the public have been pushing for a seemingly logical solution: harsher sentences for knife crime offenders.

But, in truth, we have already tried this tactic; it didn’t work. Between 2014 and 2018, the percentage of all those who received a custodial sentence, who received sentences of more than 3 months, rose from 51% to 80%. In 2014, the number of total knife crimes recorded was 23,945. In 2018 it was 39,818. There are many examples showing this trend. Harsher sentencing has failed repeatedly, and it will again. What this boils down to is inequality. Here’s why.

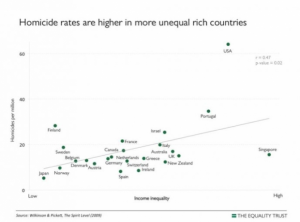

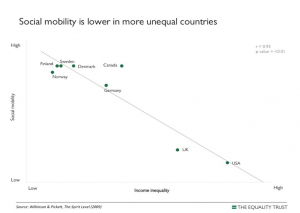

Globally, most victims and perpetrators of violent crime are young men. Experts explain this global trend with evolutionary psychology; status as the most important factor for sexual success among men, and acts of serious violence almost always as a response to, or avoidance of, feelings of shame and humiliation. (Daly & Wilson, 1988). So, for young men from disadvantaged backgrounds in more unequal societies, where distances between social classes are larger, and “where attitudes of ‘us and them’ are more entrenched”, violence is more likely to be seen as the key to social mobility. (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2011). Thus, the pattern of male violence is evolutionary, but higher rates are caused by political decisions, affecting socioeconomic equality. Working class citizens must be provided with better access to affordable housing, and better educational programmes, healthcare, training and job opportunities, in order to inhibit disenfranchisement, and enable social mobility.

Studies show that harsher sentencing and more punitive prison systems lead to higher rates of parole violations and repeat offending. Psychiatrist James Gillian states that the “most effective way to turn a non-violent person into a violent one is to send him to prison”. In the UK, reoffending rates are reported to be 65%, whereas in countries with less harsh prison environments, such as Japan and Sweden, reoffending rates are around 35%. In his interview on knife crime, British rapper, writer, and political activist Akala talks about how half the population of young offender institutes have been in care, another 50% have been expelled from school and many have been victims of domestic abuse. Prison systems that emphasise education and training programmes, mental and physical health, and good relationships between inmates, and between inmates and guards are those that prepare inmates most for life outside prison, giving them the best chance to reform and thrive in society. (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2011).

There is also a strong social gradient in imprisonment rates; people of a lower socioeconomic class are far more likely to be sent to prison than others committing the same crimes. This is also found when looking at ethnicity. Despite similar crime rates between different ethnic groups, minority groups are far more likely to be arrested, detained, charged, charged as an adult and imprisoned than their white counterparts. The odds are stacked against ethnic minorities and working-class citizens in the UK. More likely to be sent to prison, institutions that systematically worsen the life-chances of those who pass through them, already disadvantaged people face an even harder path to social mobility upon release. Inequality breeds more inequality. (ibid).

There is no correlation between tougher sentences and reduced crime. The solution to the problem is far more complex than politicians and the media are willing to suggest. All issues highlighted here are interlinked, with each affecting every another. In the simplest terms, low social mobility, high crime rates and more punitive justice systems are all caused by high inequality, and they all cause inequality to worsen. We are in a downward spiral. The solution to the knife crime problem is two-fold. Firstly, funding into welfare, education and housing must be increased, bettering social mobility and thus lessening inequality. Secondly, the judicial system must be completely restructured. Biases between ethnic groups and socioeconomic classes must be eradicated, and the prison system must be reformed to focus not on punishment, but instead on treatment and rehabilitation. High crime rates in the UK are not caused by an ‘immigration crisis’, ‘black-on-black violence’ or a ‘dangerous underclass’; they are caused by conscious decisions made in the Houses of Parliament that worsen the circumstances of millions of people, to better that of a few.

Offline resources

Daly, M. & Wilson, M., 1988. Evolutionary social psychology and family homicide. Science, 242(4878), pp.519–524.

Wilkinson, R. & Pickett, K., (2011). The spirit level. New York: Bloomsbury, pp.129-162.

0 Comments