ECR spotlight: Drew Thomas

Drew Thomas was a JRRI Early Career Fellow from May-June 2019. Here he talks about his research into the counterfeit book trade:

If you have ever visited the beautiful historic reading room at the John Rylands Library, you may have noticed the many statues carved into the stonework lining either side of the room. One of the statues depicts the most widely published author during the first two hundred years of the printing press: the Protestant reformer Martin Luther.

As she was building her collection, Enriqueta Rylands and her librarian Henry Guppy acquired several of Luther’s most important works. These were mostly short pamphlets that Luther’s supporters could read quickly and transport easily. Luther took advantage of the printing press. His pamphlets were usually printed first in his residence of Wittenberg and then reprinted in other cities, such as Augsburg, Strasbourg and Nuremberg. Pamphlets were thus fundamental inspreading his evangelical ideas.

However, even though Luther’s pamphlets were published in other cities, sometimes printers would falsely assert their reprints were printed in Wittenberg. They would emphasise ‘Wittenberg’ on their title pages and on occasion even copy the ornamental borders decorating the title pagesof the original Wittenberg editions.

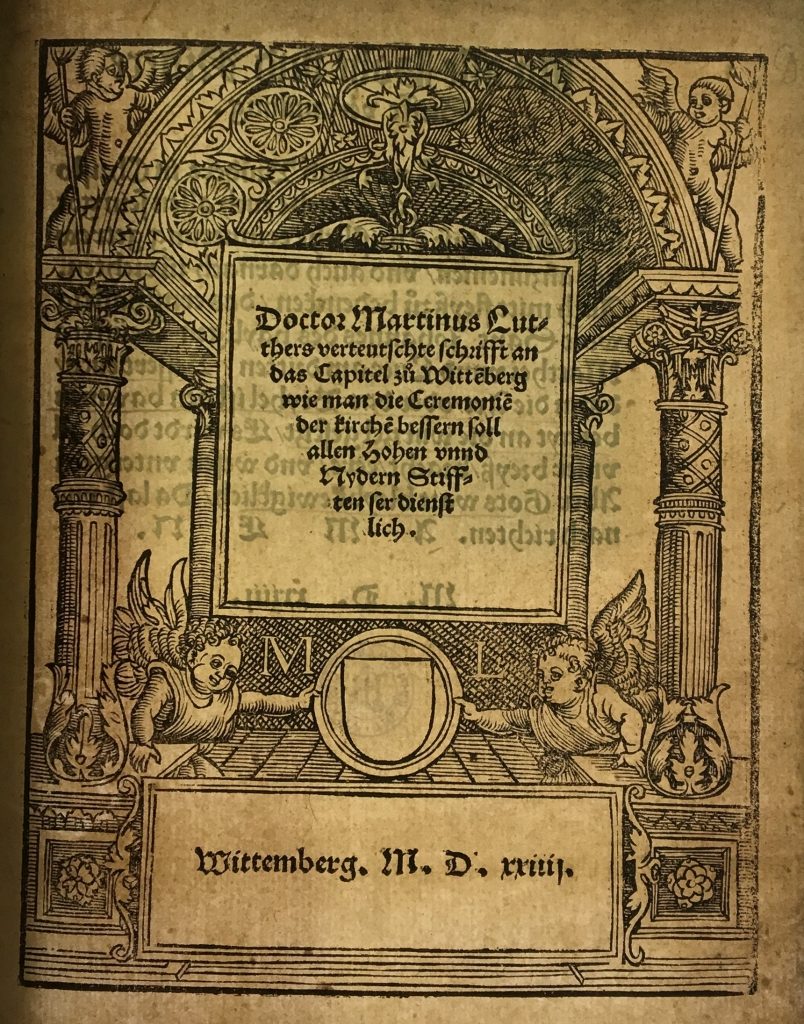

The Rylands collection includes more than a dozen copies of these Reformation counterfeits. They prominently display ‘Wittenberg’ on their title pages but were really published elsewhere. The Rylands has a pamphlet by Luther (R7438) published in 1524 that clearly states at the bottom of the title page that it was published in Wittenberg. However, it was actually published by the Augsburg printer Philipp Ulhart.

An Augsburg edition with a false Wittenberg imprint.

So how do modern scholars know where these books were really published? There are several different ways to identify counterfeits.Oftentimes, scholars can uncover the true identity of the printer by matching the typefaces, ornamental borders or ornamental initials of the counterfeits that were also used in their non-counterfeit editions.

My two months spent at the Rylands last May and June focused on a different strand of evidence; I was searching for watermarks. Watermarks are symbols embedded in early modern paper that are viewable when held up to light, like in many modern types of stationary or in various currencies of paper banknotes. Many early modern paper manufacturers used them, often acting as a logo of sorts.

My goal at the Rylands was to systematically investigate the watermarks used in the counterfeits and find matching watermarks in non-counterfeit editions. The problem is that watermarks are not easily viewable. Firstly, as these books are rare and valuable, you cannot just hold them up to the light. Instead I used a light sheet provided by the reading room, which is basically a plastic sheet nearly as thin as a sheet of paper, that illuminates, acting as a backlight.

But the format of these books posed another problem. In the print shop, multiple pages of the book were printed on a large sheet of paper, which was then folded for inclusion in the book. In the case of Luther’s pamphlets, which were nearly all quartos, each sheet of paper contained four pages on each side. This results in the watermark laying in the inner margins (the ‘gutter’ of the book) after the sheet is folded, half sticking out on one page and half on a different page. This can make the watermarks difficult to view. There is a further difficulty in that the printed text itself can also obscure the watermarks.

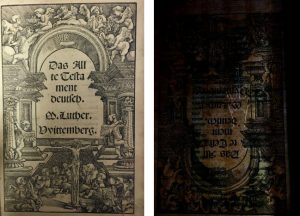

A clear example is available in a folio copy of Luther’s German translation of the Pentateuch (R28671). Using the light sheet, a watermark is visible on the title page. After applying some post-processing changes, such as adjusting the brightness and contrast, the watermark becomes even more visible.

After applying some post-processing to the image, the watermark is clearly visible.

In another example from Luther’s Ursach und antwort das junckfrawen kloester Goetlich verlassen moegen, the watermark is split between two pages (R7431). You can see the bottom half of the head of an ox on one page and the tips of the horns on another.

A watermark of an ox visible on two separate pages.

In total, I collected over two hundred images of watermarks from over 50 editions. This research marked the beginning of the creation of a repository of German watermarks from the 1520s, which will encompass samples from multiple libraries, to aid in the identification of counterfeit printers. This research would not have been possible without the generous assistance of the John Rylands Research Institute and it will add a significant new layer of evidence to my research on fraud in the Reformation print industry.

Drew Thomas is a Government of Ireland Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the School of History at University College Dublin. His current research is a digital humanities project investigating ornamentation and illustration in the early modern German book trade. He was previously a John Rylands Research Institute Postdoctoral Fellow in May and June 2019. You can follow him on Twitter at @DrewBThomasor Academia.edu. ORCID 0000-0002-9028-5251.

0 Comments