(2022-2023) How the treatment of refugees beyond the developing world reduces individuals to a state of liminal bare life

By Hannah Adhana, Jacob Andrews, Madison Leach, and Nell Tipping

Humanitarian aid is often shaped around conceptions of crisis. Redfield states that crisis suggests a sense of the ‘immediate present’ (2005), as such humanitarian aid becomes focused on survival, as this is the most pressing issue in the immediate present. One of the biggest crises discussed in the developed world is that of the perceived ‘refugee crisis’. The implications of these conceptions of crisis are that refugees are reduced to bare life (Agamben 1998) through the present need for survival. As suggested by Brun: “This notion of “emergency” then tends to “defuturize”—or empty—the future because it presents us with a heightened sense of discontinuity, rendering the future more contingent” (2016:402). Humanitarian aid’s focus on crisis has the effect of decontextualising aid recipients such as refugees from their past and future, leaving them in a state of liminality and reducing lives to biological nature alone.

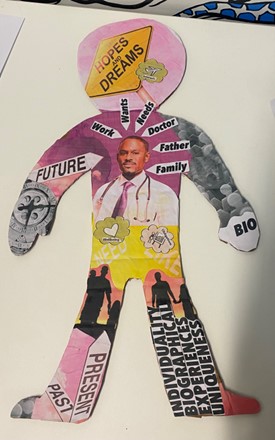

Our exhibition will explore this by showing how individuality is lost through humanitarian aid, with a specific focus on refugees in developed nations. We have created a collage with two contrasting perspectives, the first depicting the identities of refugees, their traits, wants, and aspirations and the second depicting the reduction to their biographical lives that takes place through humanitarian action, as the individual is ultimately lost upon arrival in developed countries. Our piece is a material demonstration of all that is lost through humanitarian aid when it comes to refugee identities. Our exhibit shows that a refugee who, for example, identifies as a Dad and as a friend, who has a past, potential future and wants and needs is not fully realized by humanitarian aid organizations and consequently is reduced to their biological needs alone. The collage has a theme of expectation versus reality; refugees hopes for a better life and the reality that awaits them. We argue that refugees become trapped in this precarious state as they are separated from their pasts and futures, with a focus on the immediate present and biological necessity by humanitarian actors, leaving them in a state of liminality and reducing their lives to bare life (Agamben 1998). We suggest that the rhetoric of a ‘refugee crisis’ in developed countries assists the reduction of individuality and works to decontextualize aid recipients from their pasts and futures, reducing them to no more than suffering subjects.

Hannah Ardent (1959) distinguishes between two Greek terms for life, ‘zoe’ and ‘bios’. Zoe refers to the cyclical nature of life and death, focussing on bare biological necessity whereas bios refers to the biographical content of an individual’s life, the stories, events, and experiences. Giorgio Agamben draws on these terms in his production of the notion of ‘bare life’ (1998), which describes a life focused on the zoe with no regard for bios. Through our collage, we argue that refugees are often reduced to a bare life through humanitarian action, this is made clear as on one side of the collage we see a fully realized person who is made up of both bio’s and zoe’s however on the other side we see this person losing all individuality and being reduced to purely zoological nature. Through the juxtaposition of refugee’s individual identities versus how they are perceived and treated as a ‘sea of humanity’ (Malkki 1996) by humanitarian policies, we can see how individuality (and bios) is relegated as less important than physical survival by humanitarian organisations.

In her article Humanitarian exploits: Ordinary displacement and the political economy of the global refugee regime, Georgina Ramsay states: “policy shifts only sustain survival, not meaningful livelihoods” (2020:7). For example, UK policy states that refugees are granted 28 days of asylum support once granted refugee status, after which any cash allowance and governmental support is taken away and refugees are left to fend for themselves. As a result, many refugees become reliant on services provided by humanitarian organizations such as the British Red Cross, who work to provide clothing, safe housing and advice to refugees. This necessary focus on survival allows very little room for the wants, needs and desires of refugees outside of biological necessity, hence reducing individuals to a state of bare life where they have little agency over their future prospects. In addition, this giving and taking away of support, coupled with ever changing policy, contribute to the state of liminality. In Cabot’s ethnography about the use of the pink card during the asylum process in Greece (2012), we can see how documentation both reduces people’s experiences to a piece of paper, and simultaneously traps them in a temporal limbo. “While recognition as a refugee conveys the right to protection in a host country, the category of ‘asylum seeker’ connotes a temporary relationship to a nation-state in which the right to stay is itself highly transitory” (Cabot, 2012:17). This ‘temporary relationship’ restricts the opportunities for individual growth, trapping people with no perceivable future or opportunity for a full life.

Bringing together these ideas and theories, our exhibition aims to present the contrasting identities as perceived by refugees themselves and the humanitarian organizations working in developed countries. The contrasting sides of our exhibit (the individuals versus the collective) aims to highlight the differences between refugee’s aspirations and their lived realities after migrating to developed countries. We show how individuality is lost and a collective identity of the bare, suffering subject is found in its place.

Bibliography

Agamben, G., 1998. Homo Sacer Soveriegn Power and Bare Life. Redwood City : Stanford University Press.

Arendt, H., 1959. The Human Condition. New York: Doubleday Anchor.

Brun, C., 2016. There is no Future in Humanitarianism: Emergency, Temporality and Protracted Displacement. History and Anthropology, 27(4), pp. 393-410.

Cabot, H. (2012) ‘The Governance of Things: Documenting Limbo in the Greek Asylum Procedure’, Political and Legal Anthropology Review (PoLAR), 35(1), pp. 11–29.

Malkki, L.H. (1996) ‘Speechless Emissaries: Refugees, Humanitarianism, and Dehistoricization’, Cultural Anthropology, 11(3),

Ramsay, G. (2020) ‘Humanitarian exploits: Ordinary displacement and the political economy of the global refugee regime’, Critique of Anthropology, 40(1), pp. 3–27.

Redfield, P. (2005) ‘Doctors, Borders, and Life in Crisis’, Cultural Anthropology, 20(3), pp. 328– 361.

0 Comments