Writings

Our research addresses a wide selection of comics from Argentina, Colombia and Peru from the nineteenth century to the present. Below are some sample analyses of works the research team have been looking at. We also include here some short reflections on issues related to the project by some of its advisors.

Epigrammatic racisms in Peru - Malena Bedoya

The first comic strips, known then as the ‘epigrammatic genre’, appeared in Peru at the end of the 19th century. These narratives of image and text moved between satire and irony about everyday life, especially urban life. Several cartoonists and lithographers worked on the publication El Perú Ilustrado: Semanario ilustrado para las familias (1887-1892), including Julio Gálvez, Lazarte, Enrique Góngora, Belisario Garay (Saralete) and Zenón Ramírez.

During these early years, at least until the second and third decades of the 20th century, few representations of indigenous and Afro-descendant populations appear; however, although their presence is often fleeting or discreetly worked into the compositional pictures, it is usually associated with the transformations of modern urban life and the construction of a certain distance from the rural world.

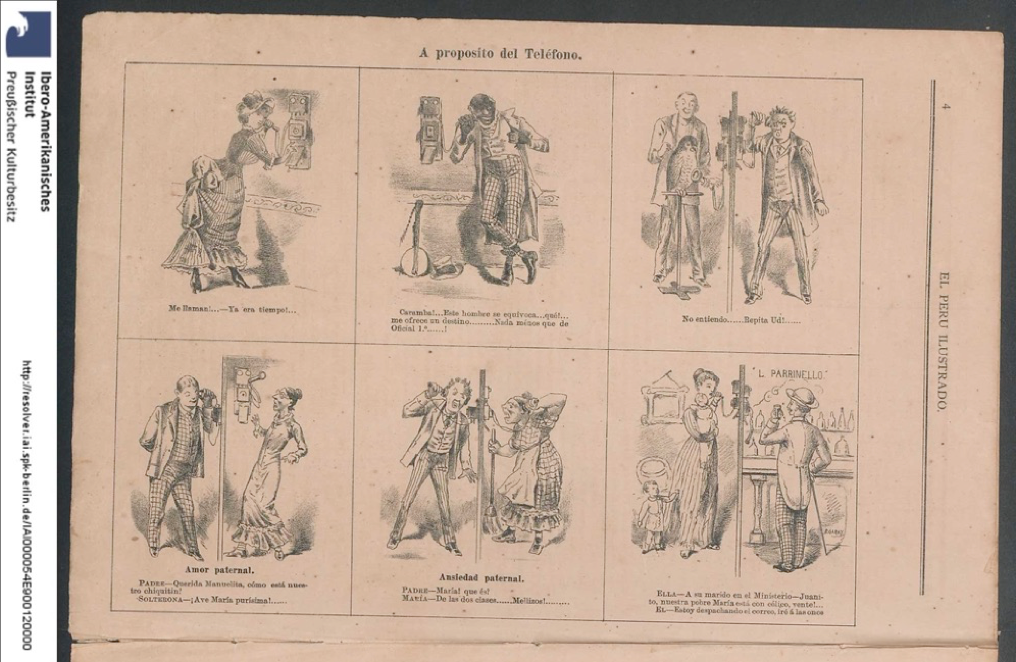

A propósito del teléfono’ by Belisario Garay, El Perú ilustrado (1887) (Institüt Ibero-Amerikanisches, (CC BY-NC-SA))

In the case of ‘A propósito del teléfono’, by Belisario Garay, published on 17 September 1887, the figure of a black man using this new form of communications technology is depicted among several characters. The figure of the racialised subject is associated with the musical instrument that accompanies him.

An ‘out-of-frame’ operates in the scene, since closure requires the reader to complete the end of the story. When the black man comments: ‘Gee, this man is wrong… what!… he offers me a destiny… nothing less than Officer 1…’, the reader-accomplice can confirm this mistake and deception through what is seen. In this situation, the closure of the story naturalises the condition of a racialized subject with no destiny given his racial status.

In fact, the commentary to the epigram mentions that these six scenes are ‘funny fantasies’, in their quality of being unreal, impossible or absurd, and therefore intended for humour.

In the comic strip ‘Las Fiestas’ published in Actualidades on 27 July 1907, the well-known cartoonist Pedro Challe presents a full page on the commemoration of Peru’s independence. Frame by frame, Challe plays with text and image to show us the events of the fiesta: that which operates outside the norm and ‘moral’ behaviour. The author distinguishes between what is and is not the ‘best of society’ and its behaviour. There is a patriotic ‘us’ and a non-patriotic ‘us’.

In two paintings, racialised subjects appear: on the one hand, ‘the provincials’, in this case indigenous people, who come from a world outside the city and who can only admire ‘our monuments’, but who cannot be part of the celebration. On the other hand, we can see a corpulent sailor with black skin and thick lips represented as expressing uncontrolled sexuality. A frightened woman appears in the painting and we see the sailor’s two hands violently ‘touching’ her arms.

Contrary to the case of the Indians and the monuments, Challe asserts a ‘we’ in this, ‘our seafaring’, since, for him, this is the boarding of a ‘minor vessel’.

Comic Cuts: Transversal Indigenous Feminisms in La sombre del altiplano - James Scorer

La sombra del altiplano – Sukermercado (Buenos Aires: Barro Editora, 2018)

Embracing the disruptive energies of the Pachamama carnival, this short zine novel depicts the violent overturning of structures of repression in the Argentine Northwest. Setting out to rescue her sister, who is incarcerated in a brothel, the protagonist Juana passes through the spirits of her ancestors, a deity who sits naked with sagging breasts and wrinkled skin midst the heights of the mountain, to take up two necromantic blades.

So armed, the indigenous vigilante creeps around the town of Tilcara, her plaits, hat and machetes throwing shadows on the walls as she traces a corrupt policeman. To the cry of ‘Quedensé atentos a estas cholas’, her swirling blades release a visual excess of blood spatters, amputated limbs and spilt guts, wielding revenge on the men who sexually exploit local indigenous women.

La sombra del altiplano fits with the wider geographies of contemporary feminist activism in Latin America, where struggles for gender equality go hand-in-hand with anti-colonial, anti-racist discourses. As such, the work speaks to Verónica Gago’s (2020) call for a network of situated and transversal feminisms.

Yet the indigenous protagonist is not the only one to wield a furious blade: the comic’s images themselves combine drawings and ink splatters with outline photographs of mountains, landscapes and houses. The comic itself thus becomes the manifestation of a violent collage, a cutting up of a patriarchal society in which indigenous women are exploited and in which LGBTQI+ graphic artists are rising up, finding their place by overturning long-standing inequalities in the comics field.

Comics, stereotypes and David Galliquio’s ‘El Negrito Joe’ - Peter Wade

Some of the literature on comics highlights the graphic quality of the form, its “drawnness”. The suggestion is that this provides a specific affordance for the reader, allowing them to be aware of the constructedness and artifice of the medium, and of the performance of the comic’s artist. The reader is asked to make connections between words and images, between panels and across gutters, thus involving the reader in the artifice.

If we think about race, what difference might comics make to the representation of race, as compared to film, text, photographs, etc? Might we be encouraged to focus on the performativity of race, and its constructedness?

This question is relevant to the common use of stereotypes (often in caricature mode) in comics, whether racial or otherwise. A blog debate discussed whether the Peruvian comic artist David Galliquio – whose work in La Mosca is highly irreverent, satirical and socially critical – uses stereotypes in a racist way.

El Negrito Joe, who features in the story The Black Man Blues, is a clear caricature, but he is used to explicitly critique racism, albeit in quite an individualistic and superficial way – Joe exacts revenge on racists who have given him a hard time by farting in their faces, urinating on them, defecating in their food, etc.

This usage is clearly different from other mass media black caricatures such as Colombia’s El Soldado Micolta or Peru’s El Negro Mama, who are played in blackface by non-black actors, with no attempt at a critique of racism. Does the graphic quality of Joe and his comics’ context encourage the reader to question the very construction of racial stereotypes? Does Galliquio’s repeated emphasis on Joe’s genitals and buttocks and on the lavatorial and animalistic nature of his acts of vengeance pander to racist (and sexist) stereotypes?

Antiracist Resilience in Crónicas de la Resiliencia - Abeyamí Ortega

Crónicas de la Resiliencia (Andrés Barragán, Juliana Ramírez, Juan Mikán, Martha Marín, Guillermo Torres Carreño)

Crónicas de la Resiliencia is a graphic novel that proposes an envisaging of the world that reformulates a re-articulation between the human and the non-human, whilst destabilising sexist, racist, and other dehumanising representational regimes that position certain lives and bodies as more valuable than others. For instance, the protagonists are members of communities historically oppressed under the matrixes of the racist-capitalist-patriarchal order: Afrodescendant women, men and young people, interacting as leaders and equals with others.

Animals, such as turtles, are key helpers to gauge the earth-saving experiments led by the protagonists. These narrative deployments resonate with Edward King and Joanna Page’s (2017) assertion about how critical posthumanisms question the construction of the category of the human as something dissociated and superior to nature, and the imposition of racialised and sexualised hierarchical inequalities among human beings.

Despite the fact that Crónicas de la Resiliencia fails to question the ultimate racial idea: that of the human “race”, the mode of political imagination that this graphic novel mobilises demands a re-envisioning of the social ecologies and the relations between the human and natural world.

Despite the fact that Crónicas de la Resiliencia fails to question the ultimate racial idea: that of the human “race”, the mode of political imagination that this graphic novel mobilises demands a re-envisioning of the social ecologies and the relations between the human and natural world.

Thus, the racialised, sexist, human-centric (and dehumanising) hegemonic imagination present in some mainstream comics and graphic novels is destabilised, placing at the centre of the narrative the voices, bodies, and experiences of subjects who have traditionally been relegated to the margins of representation.

The revaluation and repositioning of their presence are central to the idea of resilience as an antiracist, critical post-humanist, political project, that opens a fissure to reimagine a more existentially just, and sustainable, world for all beings.

¡Que tal raza!/What a nerve! - Alfredo Villar

There’s an expression used, it seems, exclusively in Peru: “¡Qué tal raza!” (literally ‘What race!’, but more colloquially, ‘What a nerve!’). It’s a phrase that refers to a certain transgression of order and is generally used when someone has gone against the norm or acted shamelessly, which means it always carries a negative connotation. It’s a phrase that, as I see it, harks back to a colonial past with a rigid social structure in which transgressors were always racialised. That such an expression is still being used in Peru indicates how deep-rooted such colonialities are in our collective imagination.

As a post- (but also neo-) colonial country we live under the aegis of the white and Western world; its institutions, likes and dislikes, and even its pleasures dominate our conscience and our most intimate desires. Peruvian comics have a long tradition of stereotypes and racial gestures that turn the Afroperuvian, Andean, and Amazonian into exotic fantasies in which the ‘non-white’ is always where difference lies.

It’s only in the last 20 years or so that we find new authors who are trying to unpack those falsely racialised and exoticised worlds. But racism persists; there has been an eternal bombardment of images and discourses that privileges whiteness and the West.

The democratisation of printing methods and the rise of independent and regional publishig houses has produced a greater diversity of writers and artists who look beyond stereotypes (or exaggerate them in carvalesque fashion like David Galliquio). The politics of these images is a field of struggle, such that we might even speak of a constant ‘war’ between native and outsider values, but that would be to simplify the constant symbolic negotiations that emerge, ones that hybridise the supposedly national with the foreign.

Peru is a country of multiple identities that simultaneously diverge from and fuse with each other. It’s in the moments of what is known in Quechua as ‘tinkuy’ or ‘coming together’ when we can find a creative response to the racisms and (neo)colonialisms imposed on us by mass media and everyday life. One of these forms of ‘tinkuy’ is what we call ‘chicha’, a blend of the highly foreign with the highly local, a fusion in which mixture has radicalised itself to such an extent that it is impossible to distinguish between or divide what comes from outside and what within. ‘Chicha’ implies an entire cultural process that starts with music and street art and that now pervades not only spheres of popular cultural but the wider national imaginary. The imagined community of ‘chicha’ is a new form of mass collectivity that emerges from the popular and that constantly contests the hegemonic. Despite its contraditions it offers new forms of hope in the occasionally desolate landscape of our national reality. Does a ‘chicha’ comic exist? Some authors or texts might be described in such a fashion but it is an area that merits further reflection.

Races, Identities, and Territories - Carla Sagástegui Heredia

Twenty years studying the history of Peruvian comics has allowed me to map its presence in the complex culture of a country that even only 50 years ago might be considered predominantly oral and rural. Asking how we have been represented in a modern form, one that is tied up with mass media and which ties together word and image (seemingly oral but essentially written), and looking at who produced these comics and with what aesthetic choices, has shaped my lines of research, which, taken together, highlight the development of an increasingly complex form and one that is ever more present in the world of art and academic research. Studying how the form addresses and engages with racial and territorial identities, the inclusion of women and homosexuality, changes in the publishing market, the press, and the comic form, the role of the Catholic Church in comics production, and the growth of the serialised Peruvian comic, have all expanded the cornerstones of cultural research, creating new viewpoints and integrating a frequently invisible public.

The child public, for example, was not the first one targeted by Peruvian comics. In fact, ever since 1887 Peruvian comics have been aimed primarily at adolescent or adult audiences. The first Peruvian comic strips with professional degrees of graphics and narrative published by the newspaper La Prensa (1952), were directed at such a public, one quick to link the three Peruvian races to the territorial regions assigned to them. Reading them you can trace that deep-rooted identification between race and territory imposed by Lima’s educated elite since the end of the 18th Century. In the 20th Century, their masculine archetypes were represented in two recurring narratives: that of the heroic, exemplary character, defender of his territory; and that of racially ridiculed characters whose actions merit punishment or contempt, particularly if, as migrants, they are found outside their designated geographic area. The plots of these comics only had male protagonists, a trait that continued even with the efforts to produce comics directed at a child audience. Studying how the visibility of this male and female child audience occurred, and how it was part of the educational impulse that used comics to educate and Westernize Peruvian children, both indigenous and mestizo (‘cholos’), was made possible thanks to research into the most significant and long-standing comic project for children, the magazine Avanzada (1953-1968). Investigating its origins and duration has shed light on a context that has been studied, but not widely disseminated: the educative and acculturation agreements made between the Catholic Church and the Peruvian State. In fact, Avanzada was published by the Obras Misionales Pontificiales (Pontifical Mission Societies) until the Revolutionary Government of the Armed Forces reappropriated the protagonists.

Examining the role of women in the history of comics is one way to study gender in Peru. In tune with the history of Peruvian feminism, women’s presence in Peruvian comics spans principally the last forty years. Addressing the lateness of this presence in comparison to other countries made it easier to separate the problem of male dominance of the press from the long-standing subjection of women to illiteracy and their isolation from the public sphere. In other countries in the region with a larger and more varied reading public, though the press was also a masculine space, access to education meant some women were involved in the publication and creation of children’s magazines, newspapers, and photo novels, and even in shaping political spaces in the press. That difference has consequences because, although female characters have appeared in Peruvian fanzines over the last 20 years, the characters that dominate the popular Peruvian imaginary are still masculine.

The fanzine and the contemporary graphic narrative, with the visual and subjective force of novelization, were consolidated in Peru in the aftermath of the conflict between Shining Path and the Peruvian State. The issue of armed conflict led a group of male authors to take the lead on shaping memories about a historical event so painful that it has truncated the consolidation of a genuine democratic system in Peru. Out of an awareness of the remonstrative nature of the graphic narrative came the realisation of a contrary function, that of a break with the traditional comic that functioned as a core device for inscribing a particular national identity on our bodies and in our imaginary. A protest that made racism, violence, and discrimination the protagonists of a comic strip turned book.

In the case of contemporary female authors, unlike their colleagues, national or territorial identity has been less of a priority than issues of gender as embodied in works of autofiction and reflections on what it means to be a woman. Among other kinds of works, Japanese manga has also been incorporated into the Peruvian comic. This tradition not only brings with it an aesthetic turn in national comics, but also opens up thematic possibilities that were underexplored in Peruvian culture, such as the prominence of sexual diversity. It remains to be seen if the prominence of these sexual identities, seemingly distant from race, expands the territories of the Peruvian imaginary or, ultimately, makes them invisible.

"We're Screwed": A Reflection on "Round Table on comics, history and racial identities" - Renso Gonzales

Some Reflections on ‘Round Table on comics, history and racial identities’ (Lima 2022)

I’m amazed by the narrative and sequence of comic strips during the golden age of Latin American comics. In this case, as referenced by Peter Wade, in the Argentine comics ‘El Negro Raúl’ and ‘Policarpio’. Both comics take place in an urban setting where the humour lies in the (dis)grace of how the characters are treated or perceived by others.

This type of humour is sometimes used with a certain subtlety and ingenuity by the author. It also refers to a time when this ‘humour’ was normalized. These two comic strips certainly reflect the idiosyncrasies of their society.

As speaker Malena Bedoya points out about ‘Mojicón’, no ethnicity has been free of qualifiers. In this Colombian comic strip children are represented as roguish juvenile characters on their way to adulthood. We notice that their visual gags are accompanied by a certain ‘tenderness’ when concluding the joke presented by the author.

Comics with child characters is a universal genre with its witticisms, antics and infinite number of themes. In ‘Mojicon’ we see a Creole character accompanied by other secondary characters of different ethnicity, where the latter generally end up being victims or ridiculed. This fiction is very close to social reality.

Abeyami Ortega makes an interesting to the comic ‘Patoruzito’ and the psychology of its characters, focusing on the antagonist, Isidorito, and the analogy of the country vs. the city, a dichotomy that offers a constant reflection on different perspectives on things, including progress, trade, etc., often manifested by the actions of the urban dweller and the Indigenous character.

Ortega also introduces a more realistic comic style with her example of ‘Hernán, el corsario’ and ‘La Araucana’. More than epic, these works might be rather dense for readers, who might try to find a referential identity about characters of similar ethnicity.

The examples, reminds us of the times when we read adventure and fantasy literature, and recognized blonde characters as heroes, those with sallow skin as traitors, and characters with darker skin as savages. When comic strips move away from humour, they can be critical, but they can also lead us to further reflection.

The contemporary comic Dora by Minaverry discussed by James Scorer, and the theme of archives, reminds me of the documentation of political cases in the comics ‘Barbarie’ by Jesús Cossio. Perhaps the antecedent of the political-social comic in Peru was the adaptation of Ciro Alegría’s novel, ‘The World is Wide and strange’, illustrated by Gonzalo Mayo.

The conference finished with Carla Sagastegui’ s paper on ‘Blackface’, classic creole and indigenous characters in Peruvian comics such as ‘Boquellanta’, ‘Coco, Vicuñin and Tacachito’, both by Hernán Bartra. Fortunately, in later years, during the decade of the 80’s and 90’s, Peru developed remarkable social comics such as ‘Piolita’ and ‘Luchín Gonzales’ by Juan Acevedo. However, the most dramatic and violent comic strip with multiracial characters was ‘Los niños de la calle’ by Raúl Kimura, a difficult comic to forget.

‘We’re screwed’ was an interjection by the Colombian character “Mojicón”.