Reconstructing the Minute Material World of Early Modern Textiles: Maarit Kalmakurki on Clothing and Textile Studies in the Digital Age

Stefan Hanß: Maarit Kalmakurki, MA, is a doctoral candidate at the Aalto University School of Arts, Design, and Architecture, Finland. Her doctoral dissertation investigates the notions of digital character’s costume design in computer-animated feature films. Maarit Kalmakurki’s diverse research interests combine dress history, stage and film costume history, and the use of technological tools in design and research processes. She is a member of the European Research Council consolidator-grant funded project Refashioning the Renaissance: Popular Groups, Fashion, and the Material and Cultural Significance of Clothing in Europe, 1550–1650, led by Professor Paula Hohti Erichsen. Maarit Kalmakurki is involved in preparing and running a masterclass on digital reconstruction of early modern garments at the British Academy event on “microscopic records”. In the following blog entry, she reflects on the possibilities of this methodology for the study of early modern textiles in general and the application of digital reconstruction methods and tools in the ERC Refashioning the Renaissance project in particular.

Maarit Kalmakurki: There has been a growing interest to utilise digital reconstruction in dress history research as it offers new ways to examine and visualise historical objects and garments. Digital reconstruction enables the creation of garments and entire outfits, based on information found from surviving garments, remnants of partially damaged cloth pieces, patterns, and written sources. My task in the ERC Refashioning the Renaissance project is to build a digital reconstruction of a seventeenth-century male doublet. The doublet is an imaginative reproduction of a garment that was recorded in Florentine artisan Francesco Tistori’s 1631 post-mortem inventory. Firstly, the Refashioning team research historical sources (images, surviving objects, archival and literary texts) that help to imagine what the doublet could have looked like. Then the historical doublet is physically recreated at the London School of Historical Dress, and thereafter, I base the digital reconstruction on the same patterns, fabrics, and sewing techniques that were used in the making of the physical doublet. The aim of the digital animation is to examine different digital reconstruction methods and to disseminate the project’s research results through the digital animation, which is much easier to share with a wide audience than a physical garment. My research is practise-based, in which I contextualise my personal observations from the making of the digital reconstruction. This corresponds with the other hands-on experiments that are conducted as part of the Refashioning project.

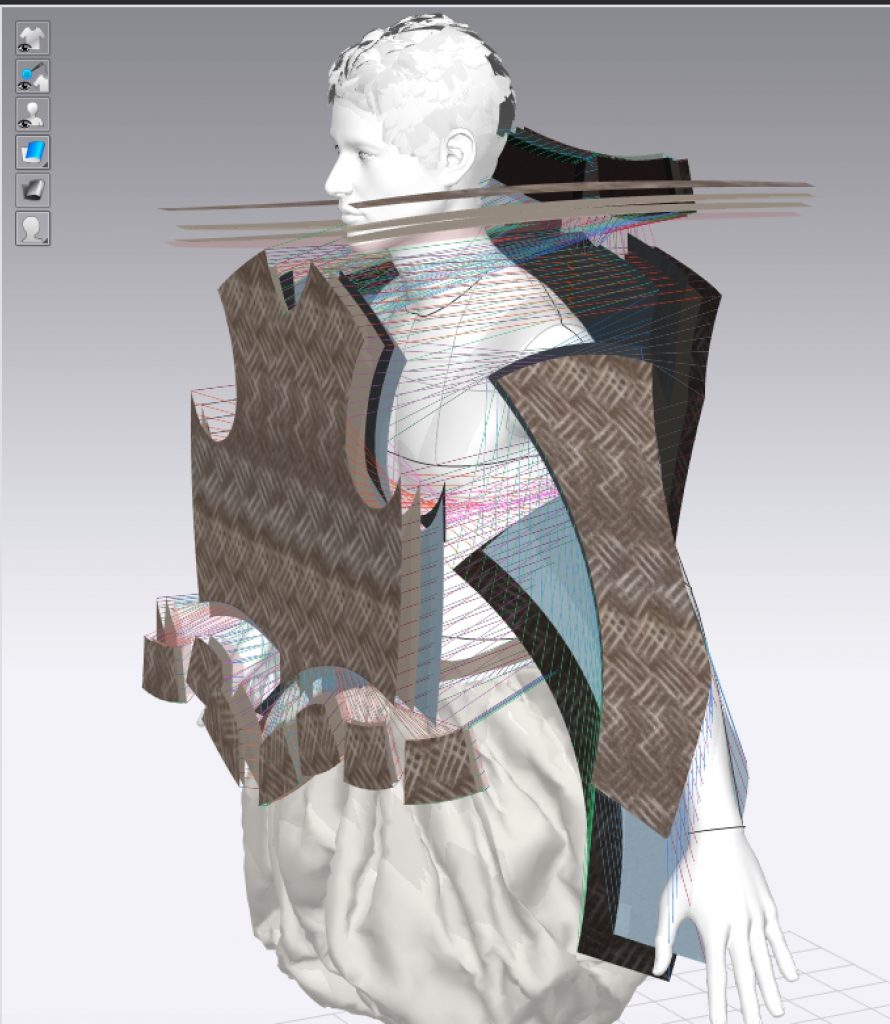

Fig. 1: Digital reconstruction visualising the complexity of historical garments. This pattern layout shows all the different pattern pieces and materials that are included in early seventeenth-century male doublet. Image credit: Maarit Kalmakurki.

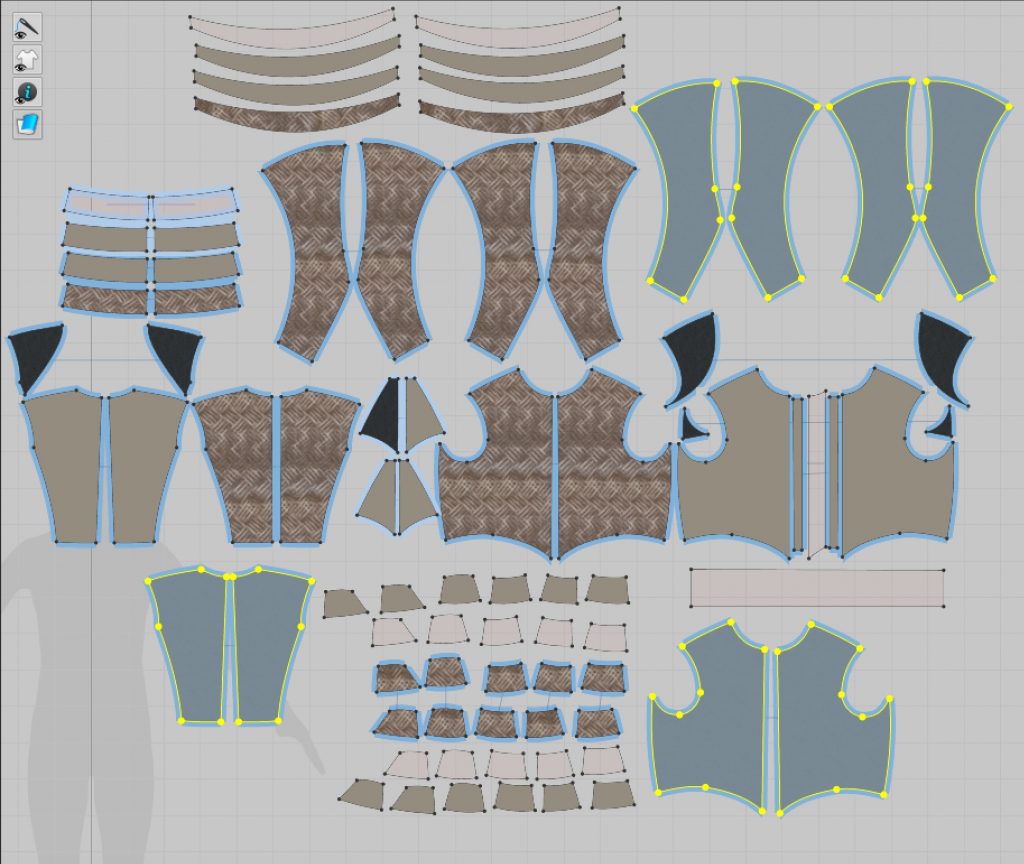

I am creating digital animation with the Clo3D program, which was originally developed for the fashion industry. There are many benefits of using Clo3D, such as the ability to build the garment with existing digital (CAD) patterns, to alter them in the program, or to create entirely new patterns. This is an important feature for research on the history of dress and fashion, as historical garment patterns often differ from contemporary designs and shapes. Considering further benefits of digital reconstruction for research on early modern dress, Clo3D also enables the visualisation of many historical garment patterns. For example, the historical doublet which I create for the Refashioning the Renaissance project (Figure 1). Digital animation furthermore allows the presentation of several layers of different fabrics that are ‘sandwiched’ together. The possibilities of doing so are often limited when examining surviving garments from that period. Producing similar examples in real life would be much more time consuming (Figure 2).

Fig. 2: Digital animation can reveal all different layers that are included in a historical doublet. It also helps illustrating where these layers were actually positioned. Image credit: Maarit Kalmakurki.

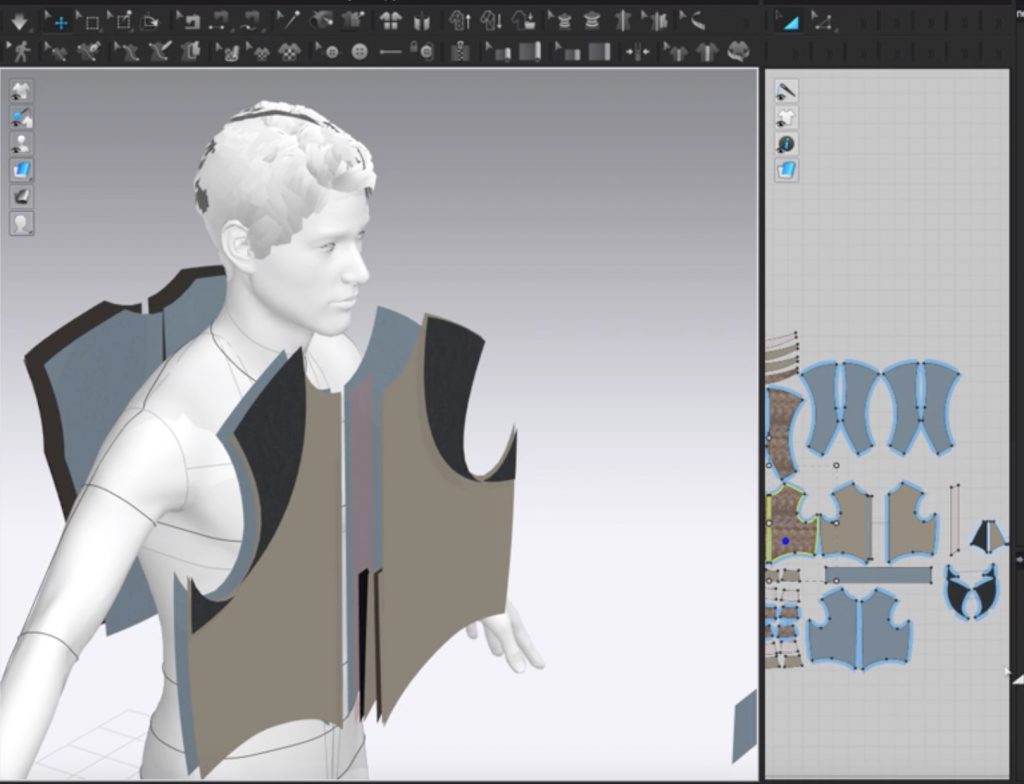

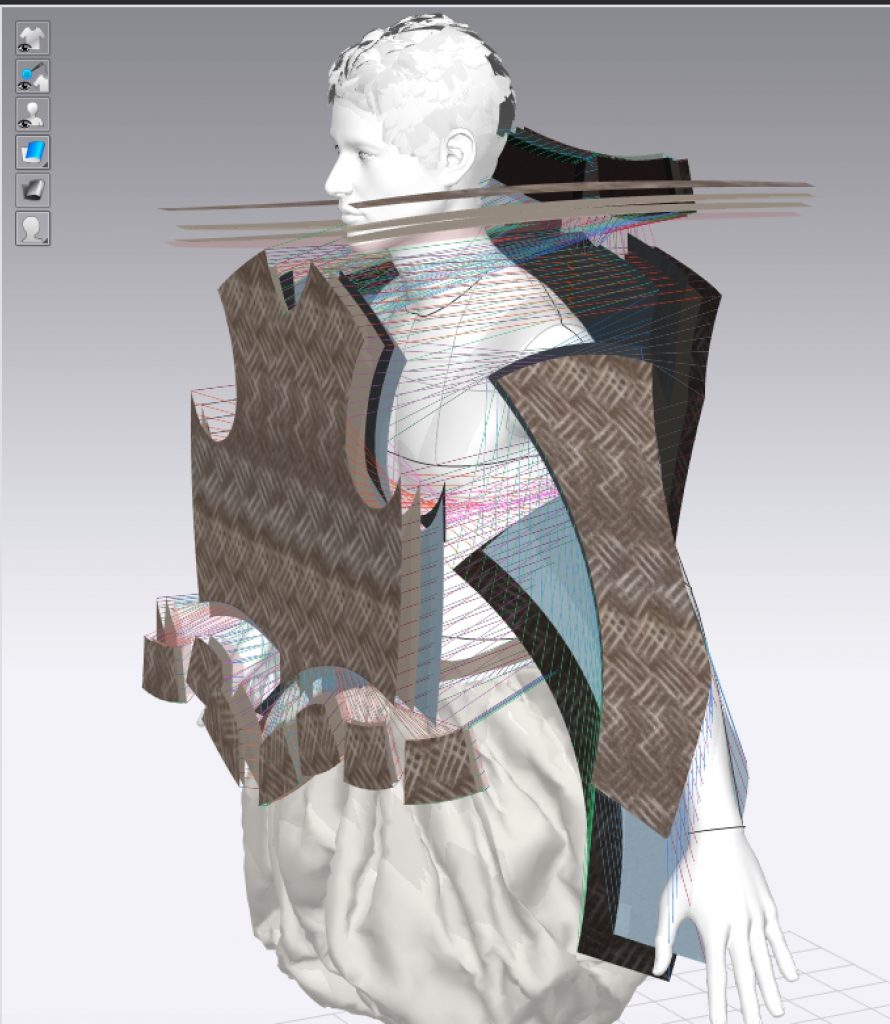

The complexity of early modern clothing can be captured digitally through the identification of sewing techniques (Figure 3). In contrast, this kind of information cannot be shown in the physical doublet version, as once the garment is made, all the complex layers and materials are hidden between the outer fabric and the lining. Digital reconstruction can furthermore imitate the same material behaviours of physical fabrics, such as the weight of the fibre or tension of the weave. This is important for animating historical garments, such as the doublet of the Refashioning the Renaissance project. Clo3D also enables inclusion of different material finishing, which means that the stamped woollen velvet that was recorded as the doublet material in the inventory of Tistori can be also visualised in the digital animation. The depiction of the different digital surface textures is a crucial tool for the digital representation of historical garments in general and their “microscopic records”, as you call it, in particular. It is crucial to visualise as accurately as possible what historical clothing looked like in order to fully grasp the minute material world of early modern garments.

Fig. 3: Digital reconstruction demonstrates the complexity of historical clothing, for example in the ways the different materials were sewn together. Image credit: Maarit Kalmakurki.

Other than visualising the different areas that are part of constructing this early modern doublet, or historical clothing in general, another benefit of digital animation is the analysis of the different areas of the garment fit, which are not possible to present with real clothing. The garment fit can be shown with fit and stress maps that indicate the areas in the garment that include pressure on the body. This information shows, for example, that male and female doublets had a particularly tight fit when being worn by early modern protagonists. Acquiring such knowledge through the physical reconstructing of historical garments would be a more time consuming and expensive process. Additionally, the digital animation can present internal lines indicating the waist, bust, or other key areas, illustrating the ways the garment fits on and around the body. This is useful in the representation of historical clothing, as their fit differs from the ways contemporary garments are worn.

The digital garment reproduction, on the other hand, differs from making the garment in real life. For example, in the digital reconstruction the inner layers of fabrics have to be removed prior to the garment simulation, i.e. when the garment is virtually sewn. Simulating the many layers of digital materials is challenging and causes problems with the garment fit. I have created a method in which the digital doublet’s shape imitates the physical version, even though it does not include all the different layers of materials that are important in the creation of the physical garment’s shape, fit, and feel. Some other adjustments are also made along the way in the digital animation, as the digital garment does not always function similarly to real life expectations.

I will discuss the different methods of digital reconstruction in more detail at the upcoming British Academy event Microscopic Records: The New Interdisciplinarity of Early Modern Studies, c. 1400–1800. I am going to run a masterclass together with Sophie Pitman, a postdoctoral researcher who leads the experimental strand of the Refashioning the Renaissance project. The masterclass focuses on the ways two-dimensional patterns transform as three-dimensional garments, the differences between digital and physical garment making, and the ways digital reconstruction can be applied in dress history research in the frame of the Refashioning project.

Further readings:

Kuzmichev, Viktor, Aleksei Moskvin and Mariia Moskvina: “Virtual Reconstruction of Historical Men’s Suit,” AUTEX Research Journal 18, no. 3 (2018): 281–294.

Kuzmichev, Viktor et al.: “Computer Reconstruction of 19th Century Trousers,” International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology 39, no. 4 (2017): 594–606.

Loscialpo, Flavia: “From the Physical to the Digital and Back: Fashion Exhibitions in the Digital Age,” International Journal of Fashion Studies 3, no. 2 (2016): 225–248.

Moskvin, Aleksei, Mariia Moskvina and Victor Kuzmichev: “Parametric Modeling of Historical Mannequins,” International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology 32, no. 3 (2019): 366–389.

Moskvin, Aleksei, Victor Kuzmichev and Mariia Moskvina: “Digital Replicas of Historical Skirts,” The Journal of the Textile Institute 110, no. 12 (2019): 1810–1826.

Maarit Kalmakurki, Aalto University

Stefan Hanß, The University of Manchester

0 Comments