Science at the Museum: An Interview with Paola Ricciardi

Stefan Hanß: Paola Ricciardi is Senior Research Scientist at the Fitzwilliam Museum, which is part of the University of Cambridge, where she is responsible for the scientific and technical analysis of cultural heritage artefacts. She has a particular expertise in non-invasive analytical methods and pioneered scientific research on medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts, but also medieval polychrome wood sculptures, and early modern portrait miniatures. She did truly astounding research with the MINIARE project, which resulted in the remarkable exhibition Colour: The Art and Science of Illuminated Manuscripts (Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge, 30 July 2016 – 2 January 2017). At the upcoming British Academy Event Microscopic Records: The New Interdisciplinarity of Early Modern Studies, c. 1400–1800, Paola Ricciardi will present together with Eyal Poleg (Queen Mary, London) their most recent, joint research on a presentation copy of the Great Bible from the library of St John’s College Cambridge, which led to the discovery of the last known portrait of Thomas Cromwell before his execution in 1540 (fig. 1). Paola Ricciardi will also run the masterclass The Scientific Analysis of Illuminated Manuscripts and Early Modern Miniatures at the British Academy event on microscopic records. In this interview, she reflects on her personal trajectory as a scientific researcher in cultural heritage studies, and the significance of microscopic records in her own research on polychrome artefacts.

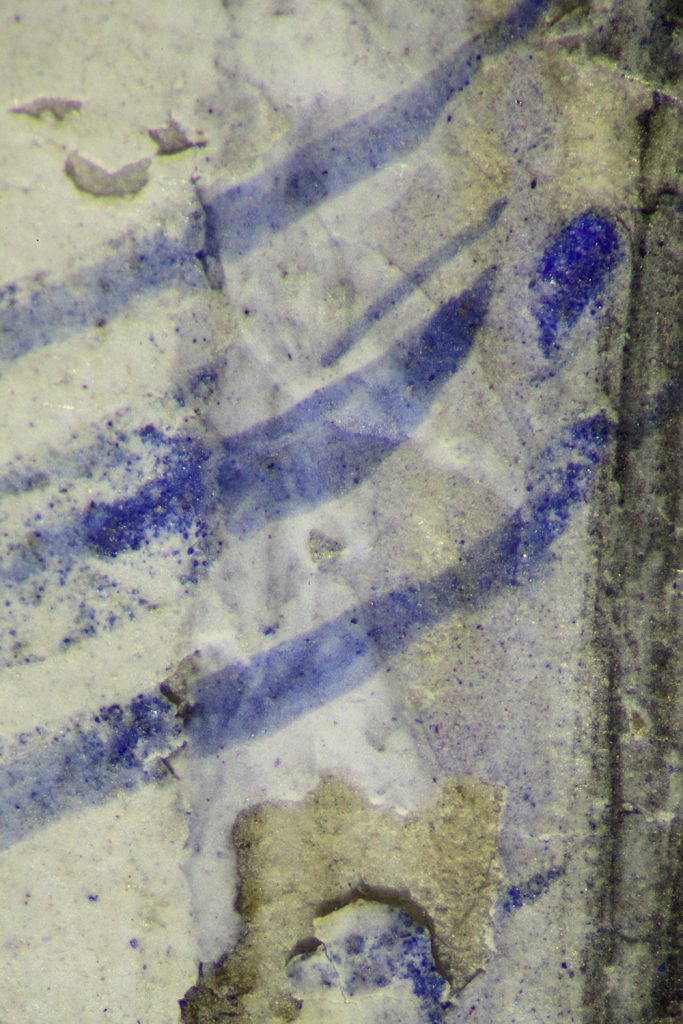

Fig. 1: Microscopic detail from the title page of a presentation copy of the Great Bible, printed in 1539 and currently in the collections of St John’s College Cambridge, showing what is believed to be the last known portrait of Thomas Cromwell before his execution. Image credit: Paola Ricciardi/St John’s College Cambridge.

SH: Still today, people commonly think about the sciences and humanities as contradictory intellectual traditions. Your biography as a researcher teaches us otherwise…

Paola Ricciardi: With an undergraduate degree in Physics, it may indeed come as a surprise to know that I have worked in art museums for the past 12 years… but I do have a PhD in Cultural Heritage Science, which prepared me for just the job I have. After a three-year post-doc at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, I joined the staff of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge in October 2011 to work on a large-scale cross-disciplinary project researching medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts, and am still very much enjoying life at the edge of the Fens. I am the Fitzwilliam’s first (and so far only!) Research Scientist; I am in charge of our Analytical Laboratory and involved in a large number of research projects as well as teaching and outreach activities.

SH: How would you explain to a wider audience what exactly a Museum scientist does? And why should historians care?

PR: Generally speaking, a ‘Heritage Scientist’—that’s the most common way to ‘brand’ my role—contributes to research, understanding and interpretation of museum collections by using a range of technical and scientific tools. This is very much a collaborative endeavor—I routinely work with curators and conservators, who usually come up with the research questions they’d like me to help answer. More often than not, my research offers some answers and a whole host of new questions for colleagues to ponder…

My own speciality is the investigation of polychrome works of art with non-invasive imaging and spectroscopic methods. Plainly put, I analyse and ‘measure’ colour on objects ranging from Bronze Age Cypriot terracotta to early modern portrait miniatures, and I do so using scientific equipment that does not require the removal of any physical samples from the objects—nor, indeed, does it require me to touch the object’s surface.

SH: You produced some truly fascinating research on the analysis of colours. What are some of the most interesting findings you made?

PR: Analysing ‘colour’ means that I can identify colourants, i.e. pigments and dyes, used to obtain the dazzling range of hues that artworks and historic objects display. Why is that important? Well, the identification of colourants can, for example, provide us with information about a medieval illuminated manuscript’s long and often complex history. This is even truer for manuscript fragments, or cuttings, which were excised from their parent books during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. When analysing an image painted by the lead fifteenth-century French illuminator Jean Bourdichon, for example, we identified bright lead white and costly ultramarine blue as the original pigments used to paint the altar cloth, but also detected lithopone and cobalt blue (fig. 2). The latter is a nineteenth-century pigment, and the introduction of lithopone can be dated even more precisely to c. 1874—allowing to establish a post-quem date for what must have been a late intervention, probably carried out to mask some damage to the object. This technical information, combined with previous knowledge about the provenance of the fragment, allowed to name which one of the fragment’s previous owners had it altered, namely Charles Brinsley Marlay, who bequeathed his collection of manuscript fragments to the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1912.

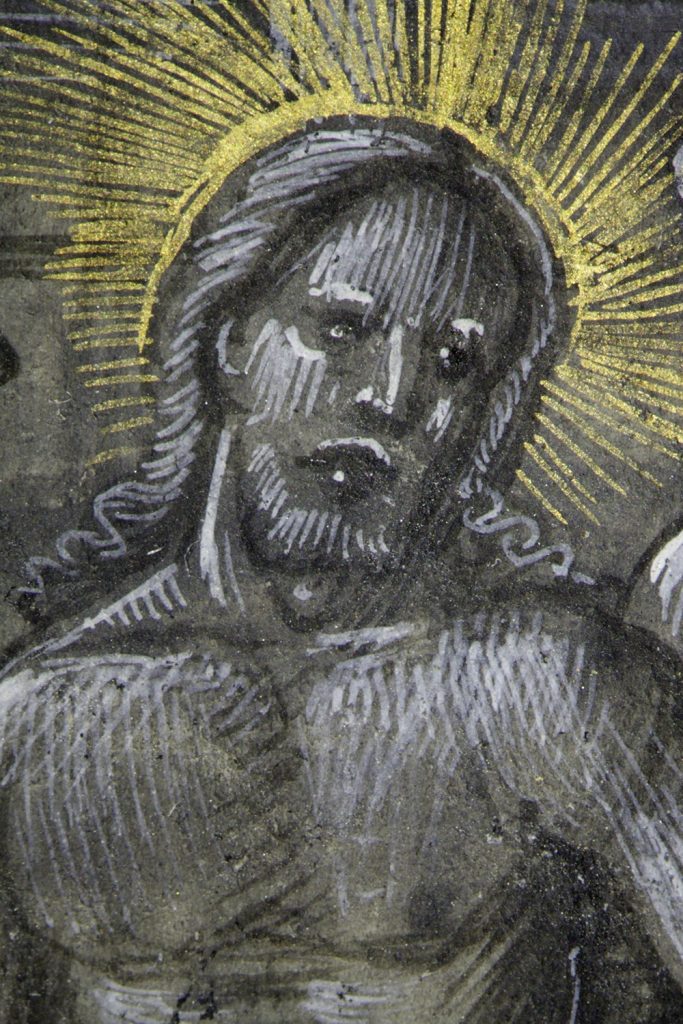

Fig. 2: Jean Bourdichon, microscopic detail from the Mass of St Gregory (Fitzwilliam Museum, Marlay cutting Fr. 6). The original blue and white pigments are visible on the left, with an area retouched in the nineteenth century visible on the right. Image credit: MINIARE/The Fitzwilliam Museum.

PR: Pigment identification is also often instrumental in learning more about the objects’ original production. Our study of five fragments from a luxury copy of the Poème sur la Passion written by Jacques le Lieur, notary and secretary to King Francis I of France, provides a really good example. These elegant miniatures were painted by the Master of Girard Acarie and his assistants, who were among the last artists to work in the manuscript trade in Rouen in the mid-sixteenth century. The Flagellation is the only one of the Fitzwilliam’s five images to display the twisted poses, exaggerated musculature and elaborate costumes characteristic of the Master of Girard Acarie’s work. It would be hard to confirm the attribution to the Master’s hand only on stylistic grounds, however, as the differences with the other miniatures are quite subtle. The Flagellation, it turns out, is the only one of these images in which we identified the unusual pigment antimony black, rather than the more common carbon-based black (fig. 3). This strongly supports the delegation of some of the work. It would not be unusual for a celebrated artist to employ a more costly and uncommon pigment exclusively, letting his assistants ‘make do’ with a cheaper alternative. This result is all the more interesting because it fits very well within a broader strand of research, which links manuscript illumination and contemporary easel painting practice. Research has shown that a number of ‘unusual’ black pigments were integral to the palette used by several Italian easel painters in the first few decades of the sixteenth century, and our work, as well as that of colleagues at the V&A Museum and Getty Conservation Institute, proves that these same pigments were also used by illuminators working in the same artistic context.

Fig. 3: Master of Girard Acarie, microscopic detail from the Flagellation (MS 355-1984). Image credit: MINIARE/The Fitzwilliam Museum.

Image credit of this interview’s featured image: XRF analysis of an illuminated manuscript. Image credit: MINIARE/The Fitzwilliam Museum.

Paola Ricciardi, The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Stefan Hanß, The University of Manchester

0 Comments