Masterclass Report I: Imaging Technologies

This masterclass was delivered by Dr Hannah Lilley (University of Birmingham) and Tony Richards (The John Rylands Library, The University of Manchester).

This masterclass report has been written by Abigail Greenall (The University of Manchester).

From its inception Microscopic Records encouraged speakers and attendees to explore the multiple ways that scientific technologies and research methods can be employed heuristically to ask new questions about early modern objects and practices. In the first of ten masterclasses to answer this call, Dr Hannah Lilley and expert photographer Tony Richards showcased the enormous potential that different imaging technologies have to capture minute palaeographical features in early modern correspondence and subsequently how this data can prompt new questions about the social, spatial and material implications of early modern writing practices.

Watch here photographer Tony Richards introducing Imaging projects at The John Rylands Library. © The John Rylands Library, University of Manchester.

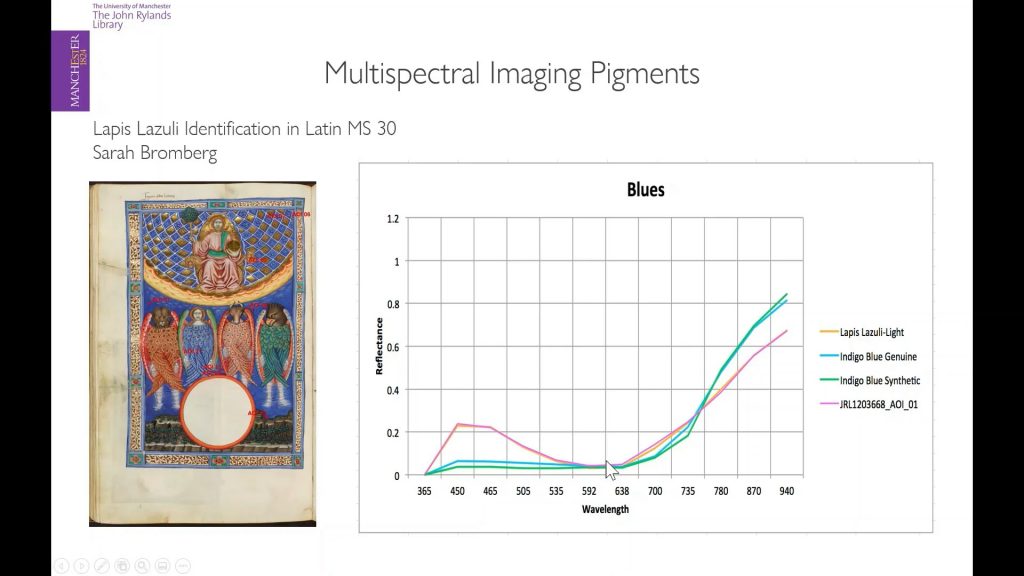

Imaging departments at research institutions across the globe are constantly developing imaging technologies to better capture archival collections and reveal new information about the items they hold. In a pre-circulated video introduction to the ground-breaking imaging projects at the John Rylands Library, Richards elaborated on the different ways that imaging workflows can be tailored to specific archival collections and research questions. Such techniques include: adapted studio lighting, focus stacking, Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), photogrammetry and multispectral imaging. By photographing objects under wavelength specific LED lighting–from UV through to near infrared–multispectral imaging can recover cleaned or faded texts and drawings, which provides one example of imaging technologies’ ability to capture details invisible to the naked eye. Lilley’s previous collaboration with Professor Richard Guest from the University of Kent offered academics attending Microscopic Records a leading example of the crucial role that early career researchers can play in furthering developments in imaging technology. Throughout her PhD, entitled Interpreting Practice: Scribes, Materials, and Occupational Identities, 1560-1640, Lilley worked with Guest to develop an image processing method that cleans and enhances digital images of manuscript letters in order to measure and extract data from individual letterforms. The workshop element of this masterclass focused on a small portion of this data.

Participants were invited to examine the similarities and differences between the scripts of two stewards who were employed separately by Lionel Cranfield, First Earl of Middlesex (1575-1645). A comparison of letters penned by the two men showed great similarities between the two hands. However, in examining quantifiable data on their respective letterforms–collected through image-processing and microscopic analysis–unique traits and differences could be identified in character perimeter, Euler (number of times the writing implement is lifted whilst forming a letter), and orientation. Nevertheless, their overall similarity was thrown into sharp relief when a third sample, from another steward employed by Sir Thomas Temple (1567-1637), was taken into account. Such a forensic approach to palaeography has the potential to reveal formerly ephemeral information about the people behind letters and their writing practices.

Lilley expertly demonstrated how this data can be interpreted through the stewards’ biographical details and the specific social and cultural contexts in which they lived. Unlike professional scribes, estate stewards appear to have adopted the aesthetic and style of script preferred by their employers, which goes a long way to explain why Lionel Cranfield’s stewards’ hands were so similar. Nonetheless, Lilley’s qualitative reading of the letters also highlights a number of variables that can explain changes in scribal technique and letterforms such as illness, deterioration of sight, physical impairment and confinement to bed. The stewards’ personal testimonies reveal that even slight deterioration in the quality of their writing caused great personal anxiety, which suggests that early modern people were inherently more sensitive to minute changes in handwriting than we are today. Understanding the impact of such happenings on the stewards’ ability to write and perform duties highlights the intimate connections between their bodies, skill and occupational identity.

The pursuing discussion between Lilley, Richards and the audience underscored the broad impact that this project and its mixture of contextual observation with forensic imaging will have on archival research carried out by early career researchers and experienced academics alike. Image processing might, for example, be employed by historians who work with manuscript writing manuals, account books and personal correspondence to reveal valuable information about children’s education and the writing practices of different social groups and genders within households. In this masterclass Lilley addressed the impact of illness on what early moderns considered ‘good handwriting’. In the closing minutes Richards confirmed that multispectral imaging could be used in the future to reveal insights about a whole host of other variables, such as emotion, on the practice of writing through the analysis of ink texture and density. These potential research avenues highlight but a few ways that imaging technologies will rejuvenate palaeographical research and connect it to key sub-disciplines in early modern history.

Abigail Greenall, The University of Manchester.

0 Comments