Consider the Strawberry: Rachel Winchcombe on Small-Scale Food Encounters in Early Colonial Northern America

Stefan Hanß: Dr Rachel Winchcombe is a cultural, environmental, food, and emotional historian of early modern England and America. Her monograph Encountering Early America discusses the broader sixteenth-century English colonial discourse about ‘the New World’ and will be published with Manchester University Press in early 2021. She also published an article on the narrative strategies of a child indentured servant sent to early seventeenth-century Virginia in Cultural & Social History. Another article entitled ‘Foodways and Emotional Currency in Early Colonial Virginia’ is forthcoming with a special issue of Environment & History. Rachel Winchcombe has been a lecturer at the University of Manchester from 2017 until 2020 and is about to embark on an ISSF Wellcome postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Leeds. From May 2021 onwards, she will start her three-year Leverhulme postdoctoral project Environment, Emotion, and Diet in the Early Anglo-American Colonies at the University of Manchester. She will be a participant at the British Academy Event Microscopic Records: The New Interdisciplinarity of Early Modern Studies, c.1400–1800 and a contributor to this event’s volume on early modern microscopic records. Her chapter will discuss the archaeobotanical and textual evidence of small-scale food encounters in the English colonies of seventeenth-century North America. In this interview, Rachel Winchcombe talks about the role of small-scale materials in her research.

Your project focuses on the history of food and connects environmental history with the history of emotions. Can you briefly outline your research interest, and how the British Academy event’s focus on microscopic records features into this?

Rachel Winchcombe: I’m particularly interested in the ways in which English settler colonists engaged with the new environments of America, especially new foods, and how this engagement impacted various emotional states. Initially, the New World provoked a significant degree of amazement and puzzlement among English observers. In 1584 Arthur Balowe, for example, a sea captain who was in the employ of Sir Walter Ralegh, undertook the first English reconnaissance of the lands that would become known as Virginia. Recounting his initial observations, Barlowe appeared captivated by the new environment in which he found himself. This region of the Americas, so Barlowe told his readers, was home to soil that was the “most plentifull, sweete, fruitfull and wholsome of all the worlde” and to “the greatest abundance” of delectable fruits, fowl, and fish.1 Early English explorers and settler colonists, like Barlowe, were equally loquacious when confronted with this radically new material environment. North America, although appearing similar to England in some respects, was home to unique flora and fauna and to botanical material that differed dramatically to that found in Europe.

Fig. 1: ‘Trade and Exchange in Newfoundland’, in Theodore de Bry, Decima Tertia pars Historiae Americanae (Frankfurt: Theodore de Bry / Matthäus Merian, 1634). Image credit: Courtesy of The John Carter Brown Library.

RW: Such encounters with new material environments were in fact often experienced and negotiated on the level of small-scale materials – or via, one might say, “microscopic records”. Analysing English travel narratives that detail environmental encounters with American foodstuffs is one way to recover how early modern protagonists engaged with new material realities in general and small-scale materials in particular. Those English settlers writing about the New World were in many cases able to distinguish between English and New World material realities and use this information to their advantage. Early modern Europeans were keenly aware of how small differences in foodstuffs could have a significant impact on their bodies. Food in the early modern period was understood in terms of its micro-components and elemental qualities. These qualities of heat and cold, moisture and dryness, had the ability to disrupt the body’s four humours (which themselves were comprised of the same material qualities) which in turn could aggravate or alleviate illness. Understanding the material differences of American produce was thus not solely a matter of curiosity, but a matter of securing and maintaining bodily and emotional health. My Leverhulme project will explore the consequences of English engagement with these new material phenomena, investigating social rituals of eating, access to food, and the connections between health, travel, and diet in a colonial context in order to reshape how we think about the interconnectedness of environmental change, bodily management, and emotional wellbeing in the early modern world.

SH: Could you give an example for such small-scale food encounters in the English colonies of North America?

RW: Take something like the strawberry. English settler colonists in North America quickly discovered that this region was home to a strawberry that appeared superior to the tiny, wild variety that was known back in Europe. Multiple writers described the differences between New World strawberries and those back in England, both visually and gustatorily. John Brereton, writing about New England described “strawberries, red and white, as sweet and much bigger than ours in England.” William Wood also found New England strawberries to be different to English ones, describing them as “very large,” with some “being two inches about.” Similarly, Roger Williams had only positive words for American strawberries. This berry, so he told his readers, “is the wonder of all the Fruits growing naturally in those parts: It is of it selfe Excellent,” adding that “one of the chiefest Doctors of England was wont to say, that God could have made, but God never did make a better Berry.”2 These descriptions of small-scale material culture, and the enthusiasm and interest that they conjure, reveal, on a larger scale, the interplay between new material environments, emotional states such as excitement, and early modern curiosity for small-scale material enquiries.

Fig. 2: “Red Straw-berries” in John Gerard, The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes (London: Adam Islip, Ioice Norton and Richard Whitakers, 1633). Image Credit: Early English Books Online.

SH: What exactly was so puzzling about theses strawberries?

RW: Whilst on the face of it these descriptions may seem like typical English hyperbole aimed at promoting the burgeoning colonies, they in fact do reflect the material differences between the English strawberry and its Virginian counterpart. Herbalists and botanists back in England took an active interest in this new variety of strawberry, emphasising its unique features whilst lamenting their inability to cultivate it successfully. John Parkinson, for example, noted that “the Virginia strawberry carryeth the greatest leafe of any other,” but because of “the want of skill, or industry to order it alright (…) scarce can one strawberry be seene ripe among a number of plantes.”3 Botanists, however, did not give up on the sweeter, larger strawberry from Virginia. Robert Morison, for example, appears to have used the seeds of Virginia strawberries to create a hybrid that became known as the “scarlet” strawberry due to its unusual colour. The scarlet remained a popular variety in England until the successful hybridisation of the Virginia strawberry with an even larger variety from Chile in Brittany in the eighteenth century. This cross of New World strawberries, known for their size and sweetness, are the forerunners of our modern-day garden strawberry.4

As well as being prized for their delectability, strawberries in the early modern period, by virtue of their specific elemental qualities, were believed to have a number of health benefits. The herbalist John Gerard categorised the temperature of strawberries, including the variety from Virginia, as being cold and moist, making them ideal for the alleviation of ‘heat of the stomack, and inflammation of the liver,’ and for ‘reviving the spirits, and making the heart merry’.5 The early modern interest in small-scale food materiality, then, can be viewed as a response to early modern understandings of the body. The micro-components of particular foods could penetrate porous and unstable early modern bodies which in turn could provoke or mitigate certain health conditions. Similar tales of settler colonists and botanists recognising, and then exploiting, botanical differences between the Old and New World for health reasons can be found in early modern travel narratives and herbals, from the cultivation of new strains of sweeter tobacco in Virginia, to the successful integration of entirely new species of plants into English diets such as the Virginia potato.

SH: Such stories of small-scale material encounters in the English colonies in seventeenth-century Northern America have often been exclusively anchored in the study of texts. How does your project set a new agenda of a combined analysis of textual and material records? What can microscopic records reveal, for example, about colonial food encounters?

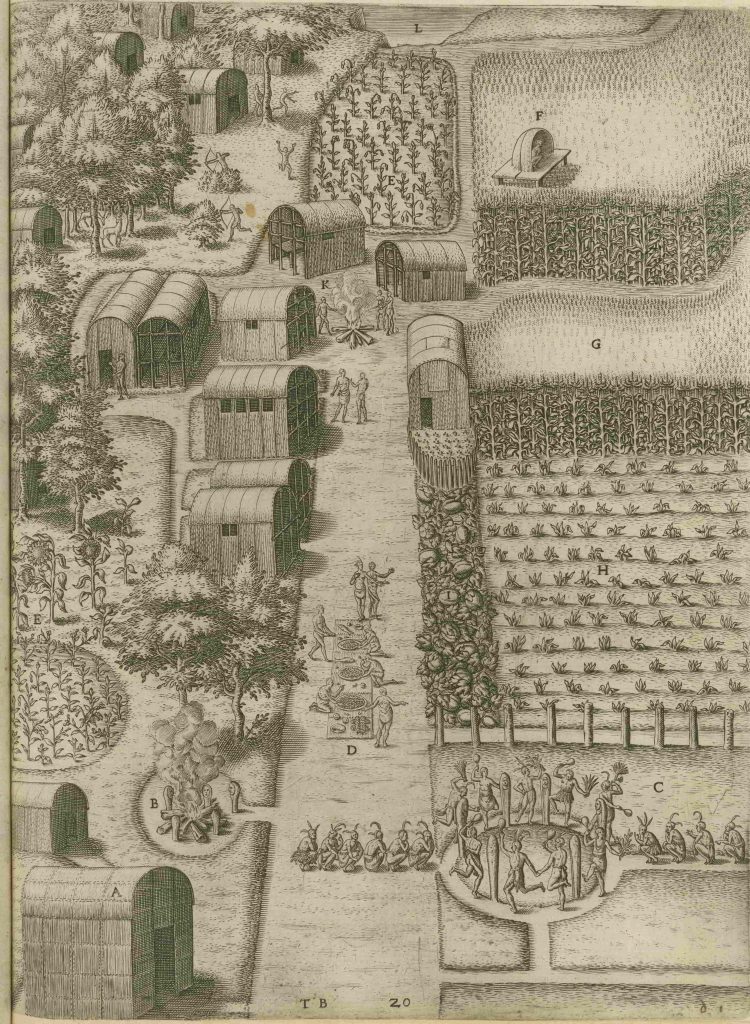

RW: The early modern material record of small-scale materials can provide exciting insights into the experimental nature of early settler diets and their reliance on Indigenous botanical knowledge. Archaeobotanical assemblages from the early years of the Jamestown colony, for example, are dominated by Indigenous cultigens and wild American produce.6 Alongside the wild berries that English explorers lauded in their writings, English diets in the New World comprised many important Indigenous crops. For example, samples from an excavated well, which was likely filled in 1611, contain botanical traces of the ‘Three Sisters’: maize, beans, and squash.7 Textual evidence from the early decades of English colonisation indicates that settlers were aware of Indigenous approaches to this kind of mixed-cropping and its ability to encourage growth and replenish soils. William Barret, for example, writing about his observations of corn cultivation in Virginia, noted how for every five corn seeds that were sown “two beanes” were planted alongside. The beans, as Barret explained, “runne upon the stalkes of the wheat [maize], as our garden pease upon stickes, which multiplie to a wonderous increase.”8 A similar observation was made my Thomas Harriot who too noted that when planting corn Indigenous farmers would “set as many Beanes and Peaze in divers places also among the seedes of Macócqwer [pumpkin], Melden [wild spinach], and Planta Solis [sunflower].”9 English colonists, then, paid close attention to Indigenous agricultural practice, particularly how seeds were sown, which in turn impacted their diets.

Fig. 3: ‘The Town of Secota with Cultivated Maize Fields’, in Thomas Harriot, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (Frankfurt: Theodore de Bry, 1590). Image credit: Courtesy of The John Carter Brown Library.

RW: Combining the study of archival and textual records with the study of early modern microscopic records and the small-scale material record of Indigenous-English encounters in the early Americas, sheds new light on the early English experience of radically different environments and foodstuffs. The lack of Old World cultigens in archaeobotanical samples suggests that English settlers were far more reliant on Indigenous foods than some historians, and indeed the writings of many colonists themselves, have previously suggested. This leaves intriguing questions to be asked about whether early settlers were either unwilling, or unable, to reshape the materiality of American environments., questions that I will explore in my chapter on small-scale food encounters in colonial North America which will be published in the volume on early modern microscopic records. Thinking about colonial encounters with small-scale materials, in this case botanical substances, then, allows us to question our current assumptions about English engagement with American environments, and indeed the American environment’s engagement with English colonists. It allows us to consider how early modern knowledge of micro-materials was put to work in order to make new material realities understandable, and in some cases profitable, how microscopic food remnants from this period can provide new insights into settler diets, Anglo-Indigenous botanical exchange, and American agricultural change, and how microscopic records themselves have shaped colonial history.

1 Arthur Barlowe, ‘The First Voyage Made to the Coasts of America, with Two Barks’, in Richard Hakluyt (ed.), The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation (London: George Bishop, Ralph Newberie, and Robert Barker, 1598–1600), 3:248–50.

2 John Brereton. A Briefe and True Relation of the Discoverie of the North Part of Virginia (London: George Bishop, 1602), 5; William Wood, New Englands Prospect (London: Thomas Cotes, 1634), 13; Roger Williams, A Key into the Language of America (London: Gregory Dexter, 1643), 98.

3 John Parkinson, A Garden of all Sorts of Pleasant Flowers (London: Humfrey Lownes and Robert Young, 1629), 528.

4 Steven Wilhelm, ‘The Garden Strawberry: A Study of Its Origin’, American Scientist 62.3 (1974), 266–67.

5 Gerard, Generall Historie of Plantes, 998–99.

6 Steven Archer, ‘Jamestown 1611 Well: Archaeobotanical Analysis Report Prepared for Historic Jamestowne’, unpublished report (2006); Justine, McKnight, ‘Archeobotanical Analysis of Archived Soil from the James Fort Period Well (STR 177)’, unpublished report (2011).

7 Ibid.

8 William Barret, A True Declaration of the Estate of the Colonie in Virginia (London: Eliot’s Court Press and William Stansby, 1610), 27–8.

9 Thomas Harriot, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (Frankfurt: Theodore de Bry, 1590), 15.

Further Reading

Earle, Rebecca: The Body of the Conquistador: Food, Race and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492–1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Eden, Trudy: The Early American Table: Food and Society in the New World. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2008.

Gentilcore, David: Food and Health in Early Modern Europe: Diet, Medicine and Society, 1450–1800. London: Bloomsbury, 2016.

Norton, Marcy: Sacred Gifts, Profane Pleasures: A History of Tobacco and Chocolate in the Atlantic World. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2008.

Purnis, Jan: “The Stomach and Early Modern Emotion.” University of Toronto Quarterly 79, no. 2 (2010): 800–818.

Reeds, Karen: “Don’t Eat, Don’t Touch: Roanoke Colonists, Natural Knowledge, and Dangerous Plants of North America,” in: European Visions: American Voices, edited by Kim Sloan, 51–57. London: British Museum Press, 2009.

Rublack, Ulinka: “Fluxes: The Early Modern Body and the Emotions,” History Workshop Journal 53 (2002): 1–16.

Shapin, Steven: “Why was ‘Custom a Second Nature’ in Early Modern Medicine?,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 93, no. 1 (2019): 1–26.

Rachel Winchcombe, The University of Manchester.

Stefan Hanß, The University of Manchester.

0 Comments