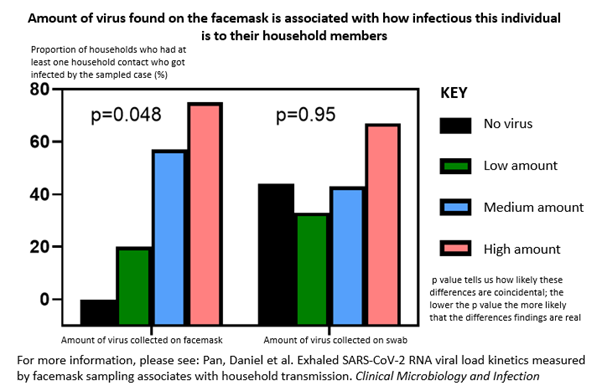

SARS-CoV-2 detected on exhaled breath by facemask sampling predicts how likely someone is to transmit to their household better than upper respiratory tract swabs.

- People who test positive for COVID-19 and breathe out virus are more likely to infect their household members than via virus sampled in their nose and throat

- People are most likely to breathe out high amounts of virus early on when they are infected

- If participants were highly symptomatic early in the first few days infection, they could produce more virus in their breath even if the virus in their nose is low

According to researchers at the University of Leicester, supported by the PROTECT National Core Study and the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), people who breathe out virus are more likely to infect their household members compared to virus sampled in their nose and throat. The findings are published in Clinical Microbiology and Infection.

Over the last ten years, the researchers have been developing technology that can capture exhaled bacteria and viruses in the breath of infected persons using modified duckbilled facemasks. In the first study that examines patterns of exhaled virus over time, the research team followed 34 healthcare workers who contracted COVID-19 between December 2020 and February 2021. Each healthcare worker provided seven modified facemask and nasal swab samples over a two-week period. Around 200 facemask and nasal swab samples were taken in total. All participants included in the study had tested positive for COVID-19 in an initial nasal swab test.

The authors found that people are most likely to breathe out high amounts of virus early on when they are infected. If participants were highly symptomatic early in the first few days of infection, they could produce more virus in their breath even if the virus in their nose is low. Most importantly, the higher the amount of virus captured by facemask sampling, the more likely that participant was to infect their household contacts by the end of the study. This last finding was not seen in virus captured on the nasal swabs.

Dr Daniel Pan, NIHR Doctoral Research Fellow and Specialist Registrar in Infectious Diseases at the University of Leicester and University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust is lead author of the paper. He said: ‘this paper provides further evidence that the majority of SARS-CoV-2 transmission depends on the amount of virus from the breath of infected individuals. In fact, some people could be breathing out large amounts of virus whilst having low amounts of virus on their nose swab. Our results emphasise the continued importance of reducing exposure to airborne virus by universal masking, physical distancing and increased room ventilation.’

Prof Mike Barer, Professor of Clinical Microbiology at the University of Leicester and Honorary Consultant at University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust is senior author of the paper. He said: ‘This paper, and another we now have online on TB transmission, are landmarks in our facemask work. Originating 20 years ago, following a TB outbreak in Leicester, we began to explore whether masks could be used to study airborne infections. It took us ten years to establish a workable method. These papers provide the first clear but perhaps unsurprising evidence that what individuals breathe out into masks indicates how infectious they are. Supported by the PROTECT National Core Study, we have opened a new door into better understanding and combatting respiratory infection.’

Prof Cath Noakes, who leads the transmission modelling theme within PROTECT, said: ‘The results from this study are really significant for understanding how and when Covid-19 transmits. The association between higher transmission rates and measured virus from exhaled breath adds further evidence that aerosols play an important role in transmission.’

The paper: ‘Exhaled SARS-CoV-2 RNA viral load kinetics measured by facemask sampling associates with household transmission’ will be published in print, in the February 2023 issue of Clinical Microbiology and Infection.

0 Comments