Renaissance Clothing and Craftspeople: Paula Hohti Erichsen on the Microscopic Records of Early Modern Textiles in the Age of Digital and Hands-On Research

Stefan Hanß: Paula Hohti Erichsen, Associate Professor of the History of Art and Culture at Aalto University, is an expert of Italian Renaissance textiles, fashion, and the decorative arts. She is scientific director of the European Research Council consolidator-grant funded project Refashioning the Renaissance: Popular Groups, Fashion, and the Material and Cultural Significance of Clothing in Europe, 1550–1650. Sophie Pitman and Maarit Kalmakurki, members of this ERC research group, will present their research and run a masterclass at the upcoming British Academy event Microscopic Records: The New Interdisciplinarity of Early Modern Studies, c. 1400–1800.

Your project group brings text-based research into a conversation with material-based research on dress in Renaissance Italy. One particularly innovative and exciting strand of this ERC project is the development of methodological approaches that focus on remaking and the digital reconstruction of sometimes partially lost textiles from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Could you elaborate a bit more on the significance of reconstruction for research on early modern textiles?

Paula Hohti Erichsen: One of the main problems for material culture historians is that we often find interesting objects in our historical records, but we do not know what these objects originally looked like. For example, our project has created a database of 30,000 clothing items that used to belong to early modern artisans and shopkeepers, based on archival documents from Siena, Florence and Venice in 1550–1650, but how these items were exactly made and what tools were used to manufacture them remains unclear. This is especially the case with items that used to belong to poorer members of society, who left few possessions behind. Even archaeological objects provide often only stratified evidence because few garments and textiles have survived and those that did are often worn out or fragmented, or the colours have faded.

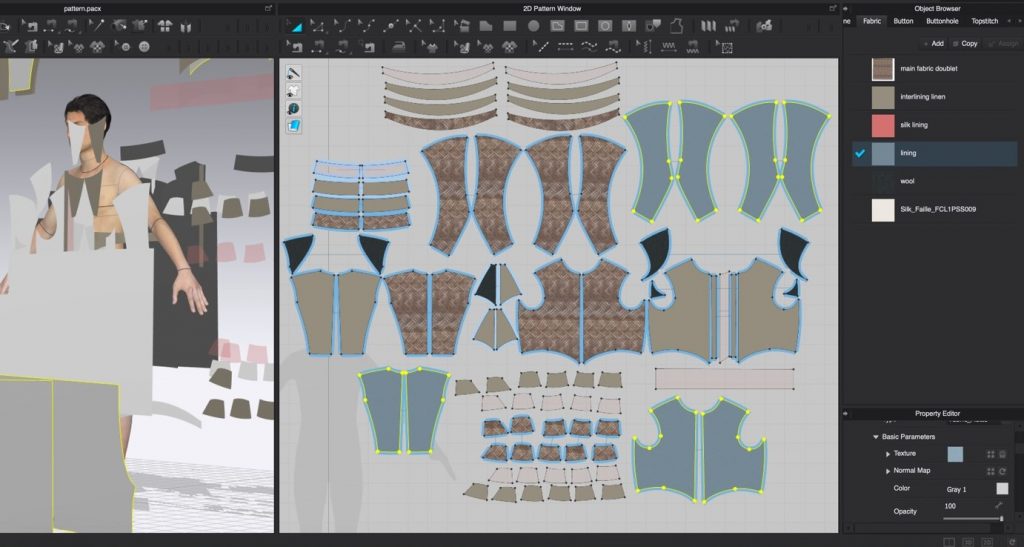

Historical reconstruction offers a new and exciting way to study past material objects, to visualise historical data, and to gain a better understanding of them. Our team works with several experiments. We spend time in labs studying how we can use sixteenth-century recipes and techniques in our work, we take courses and training in historical textile techniques, and we collaborate with craft experts to bring alive some of the historical objects that we find in our documents. For example, we have started a major historical reconstruction project with the London School of Historical Dress, to reconstruct a male doublet—a fantastic imitation piece—that used to belong to one of our seventeenth-century Florentine artisans named Francesco. We have also initiated a citizen science knitting project, with twenty voluntary knitters helping us to reconstruct seventeenth-century knitted stockings.

Projects such as these allow us to gain a more accurate understanding both of what the products looked like as well as of the technical processes and experiences that were associated with making and wearing these early modern items. This kind of information cannot be gained from textbooks or visual sources.

Combining written and visual research with re-making and reconstruction is a relatively new way of studying history. This means that we are still lacking proper methodological tools. Our aim in my ERC project is to test various experimental methods and analyse, in collaboration with our colleagues, how this kind of experimental work can be developed as a methodology in historical work. As part of this goal, we have also experimented with how digital reconstruction can be used to support and disseminate our research results, for example through animation or digital printing.

Digital reconstruction of seventeenth-century doublet patterns. Image credit: Maarit Kalmakurki.

SH: The upcoming British Academy event focuses on early modern microscopic records, thus, the small-scale world of materiality which is often hardly visible. Scientific and digital tools offer new means to explore and present information embedded in the microscopic record of early modern material culture. How do you encounter small-scale materialities in your research project? What is the value of information embedded in microscopic records, for example, for the reconstruction of early modern textiles?

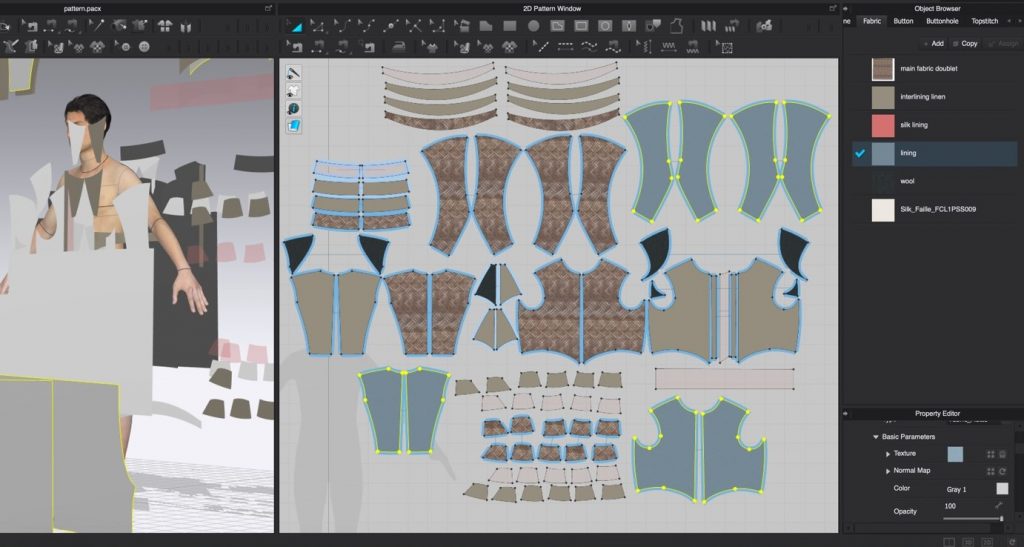

PHE: Historical reconstruction requires careful examination of the techniques and materials that were used in the original product. We have used microscopic research and scientific analysis in our reconstructions to gain a more accurate sense of the material components that were present in the original items. For example, we carried out both fibre analysis (SEM microscope and EDS analysis done at the Aalto Nano microscopy lab) and chromatographic analysis (SEM-EDX technique done at the Rijksmuseum) as part of our silk stocking knitting reconstruction project, using a small sample taken from the original seventeenth-century silk stocking, so that we could identify the character and nature of fibres, organic colorants and chemical elements that were found in the historical stocking.

This information allowed us to source materials and develop techniques that would be as close to the originals as possible. The analyses revealed that the original stocking was made of bombyx mori silk (a domestic silk moth that eats mulberry leaves), and it was originally black, with possibly alder bark used to produce iron acetate through fermentation in the so called “lasagne method”. As a consequence, we were able to commission the hand-reeled bombyx silk yarn from a Calabrian co-operative, and establish the kind of expertise and ingredients that we will need to re-create the original colour and dyeing method.

Microscopic analysis of the stocking fibres. Image credit: Refashioning the Renaissance project .

Producing silk yarn from cocoons in Nido di seta, Calabria. Image credit: Refashioning the Renaissance project.

Knitted samples created by our voluntary knitters. Image credit: Virpi Tarvo.

Original silk stocking, 1668, Turku Cathedral, Finland. Image credit: Refashioning the Renaissance project.

Reconstructed silk stocking by one of our voluntary knitters, Liisa Kylmänen. Image credit: Liisa Kylmänen.

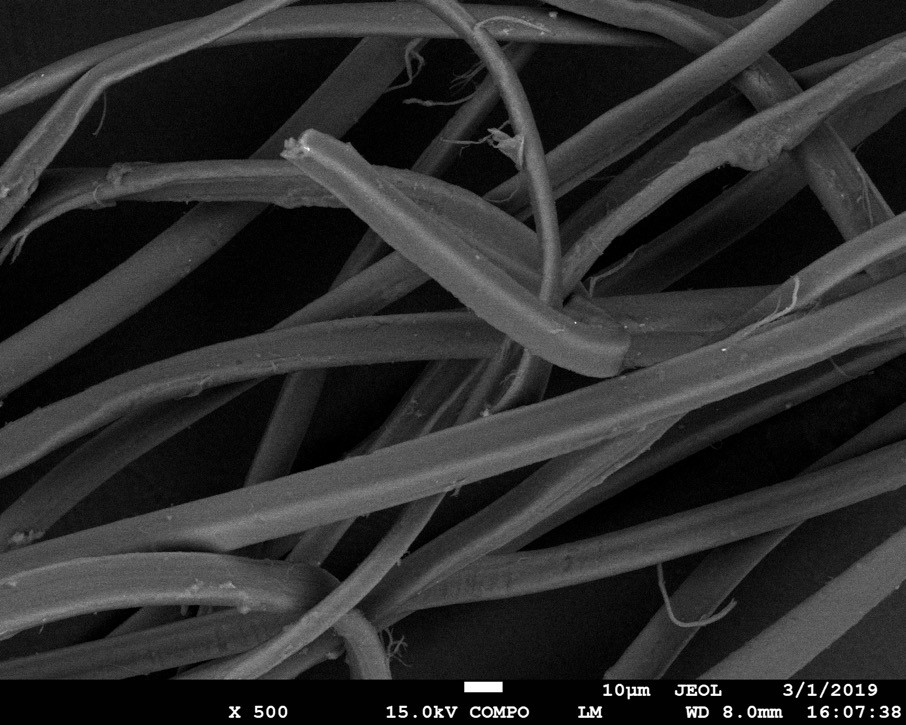

SH: In July, your new monograph will be published with Amsterdam University Press’s trendsetting book series Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700. In Artisans, Objects and Everyday Life in Renaissance Italy: The Material Culture of the Middling Class, you explore how artisans, local traders, and shopkeepers experienced “the material Renaissance”, thus, a period of heightened awareness of materiality. What have been the most exciting research findings for you? And can you exemplify how Renaissance Italian artisans were engaging with the contemporary material world?

PHE: My book explores how ‘ordinary’ Italians, such as shoemakers, bakers and innkeepers, connected with Renaissance culture: how they lived and worked, managed their household economies and consumption, socialised in their homes, and engaged with the arts and the markets for luxury goods. It tries to establish a framework for defining an ‘artisan’ and demonstrates the complexity and versatility of the topic.

Paula Hohti Erichsen’s new monograph will be published with Amsterdam University Press in July 2020. Image credit: AUP/Paula Hohti Erichsen.

PHE: The most exciting discovery during my research was the richness of the material culture at the lower levels of society. I want to show in my book that, although the economic and social status of local craftsmen and traders was relatively low, the material possessions of Italian artisans and small shopkeepers show how these men and women who rarely make it into the history books were fully engaged with contemporary culture, cultural customs and the urban way of life.

Our current ERC-Refashioning project builds on the findings of this book. The close engagement with Renaissance culture not just of the economic and social elites but also of the modest artisans and small shopkeepers further down the social scale becomes visible especially in the world of clothing and fashion, for example through the increasing availability and use of novelties, imitations and cheaper substitutes of elite fashion manufactures.

Paula Hohti Erichsen, Aalto University

Stefan Hanß, The University of Manchester

0 Comments