The Multispecies Material World of Early Modern Microscopic Records: Sasha Handley on Ghosts, Bed-Sheets, Posset, and Soporifics

Stefan Hanß: In one of our previous blog entries on “microscopic records”, we discussed the importance of collaborative research environments: open office doors open up new questions and lead to explorations in how to tackle such research questions in novel ways. Professor Sasha Handley, a social and cultural historian of the early modern British Isles, is one of these colleagues in Manchester who leave their doors open. She leads the Embodied Emotions research group and we co-organise the material culture seminar series Affective Artefacts. Her monograph Sleep in Early Modern England (Yale University Press, 2016) won the Social History Society Prize and was shortlisted for the Wolfson Prize and Longman History Today Award in 2017. Her research explores new paths in the history of sleep, religious and supernatural beliefs, and the history of emotions. As an advisor, she is supporting the preparation of the British Academy event Microscopic Records: The New Interdisciplinarity of Early Modern Studies, c. 1400–1800, which explores the often invisible world of small-scale materiality. In the early modern period, microscopic records were anchored in a multispecies material world of encounters between animals, humans, materials, plants, and even the supernatural. Sasha Handley’s research explores such multispecies material encounters evident in hardly visible, small-scale materialities. She took the time to reply to some questions.

Microscopic records draw our attention to the hardly visible material world. Some early modern protagonists would have associated the invisible material world with the supernatural realm. Seventeenth-century English pamphlets and treatises reported about “the wonders of the invisible world”, which had been “discovered to spirituall eyes.” Early modern material environments were animated, agentive, and sometimes inhabited. At times, they were fuelled by agentive supernatural forces. How did you encounter these “unseen worlds” in your research on early modern supernatural beliefs?

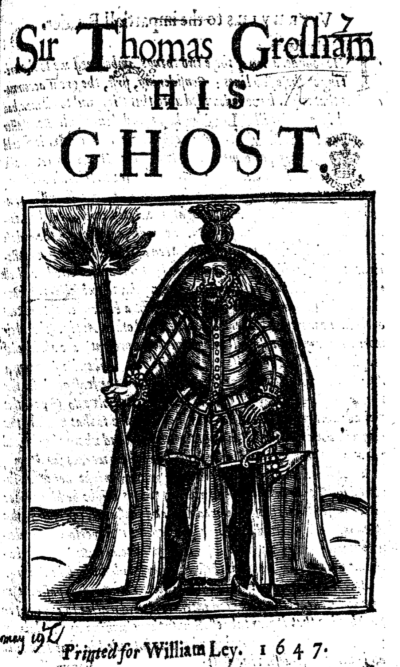

Sasha Handley: In my first book Visions of an Unseen World (Routledge, 2007), I focused on how my recovery of so many colourful ghost reports from the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries challenge dominant paradigms of the so-called ‘disenchantment of the world’. The visceral and fleshy way in which people described ghosts struck me from an early stage. They were not translucent or immaterial figures but solid, often familiar to those that saw them and sometimes wearing the same clothes that they had been known to wear when still living (fig. 1). Even unfriendly spirits, whether visible to human eyes or not, were understood to have material qualities, hence why people believed they might defeat their diabolical predators by throwing things at them, shooting them with pistols, or by setting their dogs on them. My research showed that a combination of material and spiritual weapons were routinely used to fend off unwelcome visitors of this kind. Part of my mission was to think carefully about the contexts in which ghostly visions remained resonant and emotional experiences for particular individuals and communities and to understand how they explained them in particular ways, often without recourse to the published sceptical commentaries of philosophers that often insisted on drawing a clear dividing line between the supernatural and material realms.

Fig. 1: Anon., Sir Thomas Gresham HIS GHOST (Printed for William Ley, London: 1647), titlepage. Image credit: EEBO.

Sasha Handley: Since taking the ‘material turn’ in my own research a few years ago, I am increasingly interested in the rituals and materials of protection that people may have used to defend their households (and themselves) from unfriendly spirits. Much research remains to be done by archaeologists and historians in this area but these rituals may have included inscriptions and ritual marks on bedsteads, the use of protective objects and charms such as iron knives and necklaces made of wolves’ teeth, and concealed objects such as shoes, garments, and so-called “witch bottles” that were placed inside chimneys, walls and beneath the threshold of doors. Some people even hoped to be saved from diabolical spirits by diving beneath a simple linen bedsheet. This ordinary household textile was invested with protective qualities because of its material properties (which can be viewed in incredible detail through microscopic analysis) and because of its well-established use in liturgical contexts. I hope to delve deeper into people’s understandings of the relationship between the material and supernatural realms in a book that I am writing about a Lincolnshire haunting from the early eighteenth century.

Stefan Hanß: In a History Workshop Journal article from 2018, you build on your interest in early modern bedsheets and suggest that using microscopy helps studying the emotional world of early modern materials that could connect the living with the dead. What are the insights that can be gained from the analysis of microscopic records of early modern artefacts?

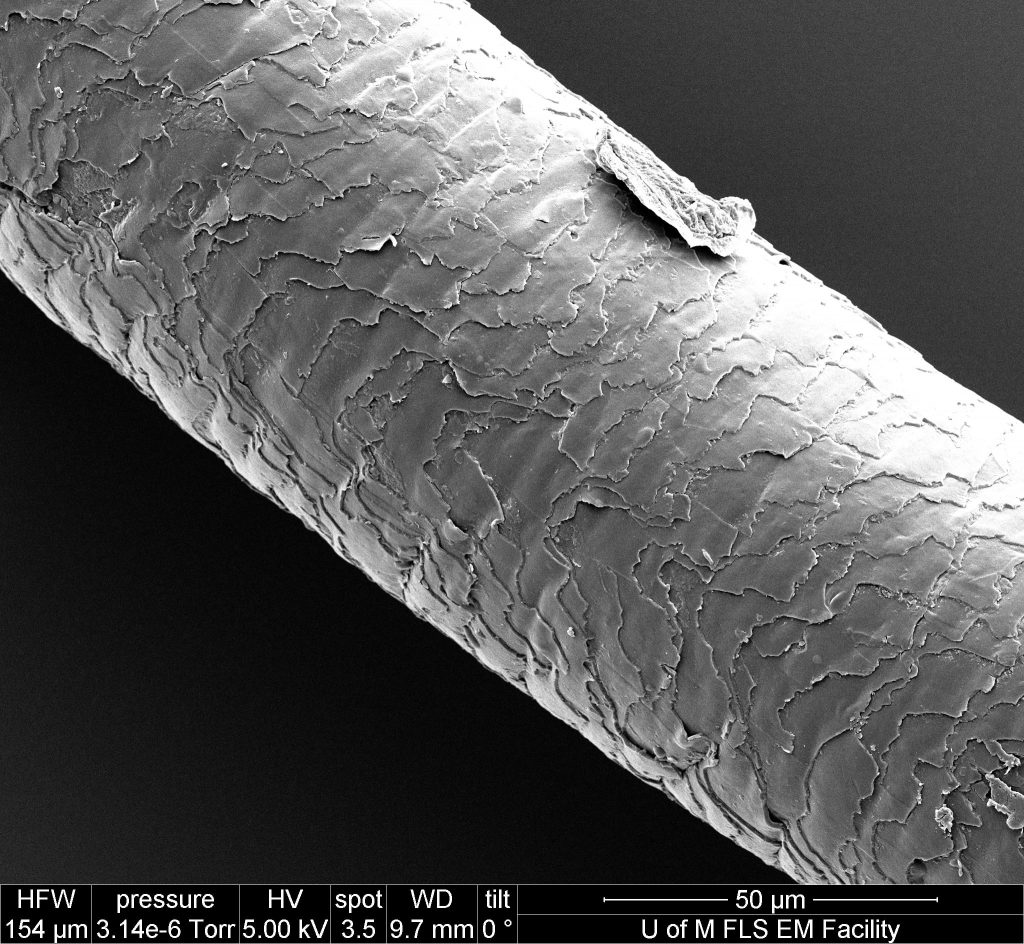

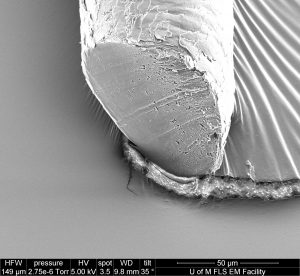

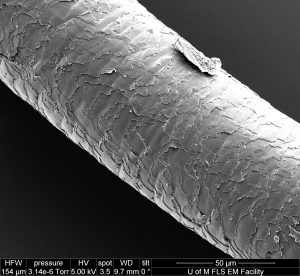

Sasha Handley: For my article ‘Objects, Emotions and an Early Modern Bed-sheet’, I was able to closely examine one incredibly evocative bed-sheet in the Museum of London’s collection to recover an emotional history of one woman’s grief and mourning following her husband’s execution for high treason. The sheet, which has never been on public display, has a very powerful inscription embroidered on it, which reads “The sheet off my dear x dear Lord’s Bed in the wretched Tower of London February 1716 x”. The linguistic power of this message is overshadowed by its materiality because the inscription is actually sewn with hair. It was only with the help of my wonderful colleague, Andrew Chamberlain—a Professor of Bioarchaeology at the University of Manchester—and the assistance of three wonderful curators at the Museum of London—Beatrice Behlen, Hilary Davidson and Melina Plottu—that I was able to use microscopic analysis to get a close view of the hair inscription (fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Microscopic analysis of two hair samples from an embroidered linen bed-sheet, Museum of London, 34.63. Image credit: Sasha Handley.

Sasha Handley: Taking tiny samples of the hair from the reverse of the sheet, we examined it with a Quanta 250 Field Emission Gun Scanning Electron Microscope, and compared those samples with a modern specimen of human head hair. From this analysis, we were able to definitely say that it was indeed human head hair, likely of European origin, which was clear from the diameter of the hair strands and the cuticular scale patterns that cannot be seen with the naked eye. We could also tell that the hair was from two different people and that it had abraded over time, signalling its age. These crucial details, alongside textual and iconographic evidence, led me to conclude that the hair was a combination of the bereaved widow and her deceased husband. Microscopic analysis also made it clear to me how incredibly difficult the process of sewing with hair must have been, given the incredible thinness and slipperiness of hair in comparison to silk or cotton thread. The careful and drawn-out labour involved led me to think about how it was made and about the levels of needlework skill and education in the period, which were staggeringly sophisticated. The microscopic analysis of the hair samples completely transformed the research. It elevated the emotional significance of the bed-sheet to unexpected heights and it was crucial in helping me to locate it within contemporary cultures of political and religious strife, as well as personal mourning. This project remains my most enjoyable research experience to date—I absolutely loved it!

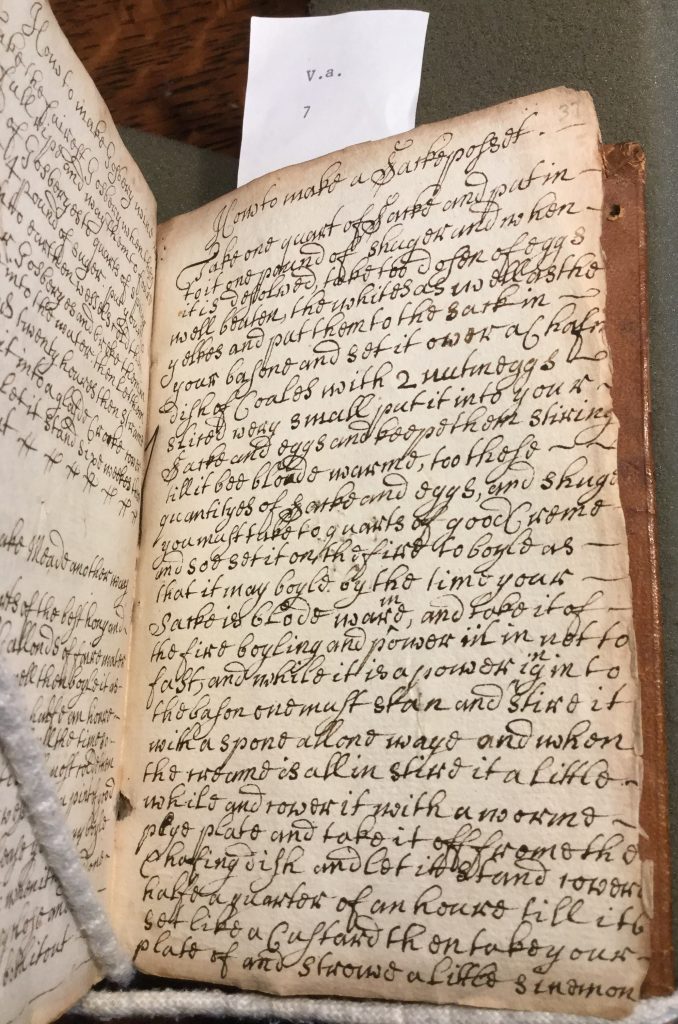

Fig. 3: A seventeenth-century recipe of “how to make a Sackeposset” documents the multiplicity of non-human materials involved in the making of posset. Image credit: Folger Shakespeare Library/Sasha Handley.

Stefan Hanß: At the upcoming British Academy event, you will speak about your recent research on “posset”. What does posset tell early modern historians about the hardly visible and often surprisingly agentive world of tiny materialities?

Sasha Handley: I have been interested in “posset” for some time as part of my growing interest in early modern foodways and environmental history, which I see as natural extensions of my interest in material histories. In early modern England, posset was a warm milk-based drink that was a household staple. Its basic recipe of milk and eggs was widely adjusted with the addition of herbs, spices, alcohol, almonds and even bread to treat an array of common physical ailments, but also to create lavish beverages suitable for important lifecycle celebrations. In the autumn of 2019 I was lucky enough to spend some time at the Folger Shakespeare Library, where I delved into their outstanding collection of manuscript recipe books. I uncovered hundreds of recipes for various types of posset, including a large number for something called “sack posset”, which was routinely served to newlyweds to end a day of wedding festivities in the seventeenth century (fig. 3). Sack posset’s core ingredient of milk was believed to promote particular affective states and behaviours such as lustfulness that were very helpful for a wedding night and that helped support the fertility fortunes of the newlyweds. As well as reconstructing the social contexts in which posset was used, and the cookery methods used to make it, I was eager to trace the multiplicity of non-human materials, species and agricultural practices that were essential to the production of posset’s core ingredients (fig. 4).

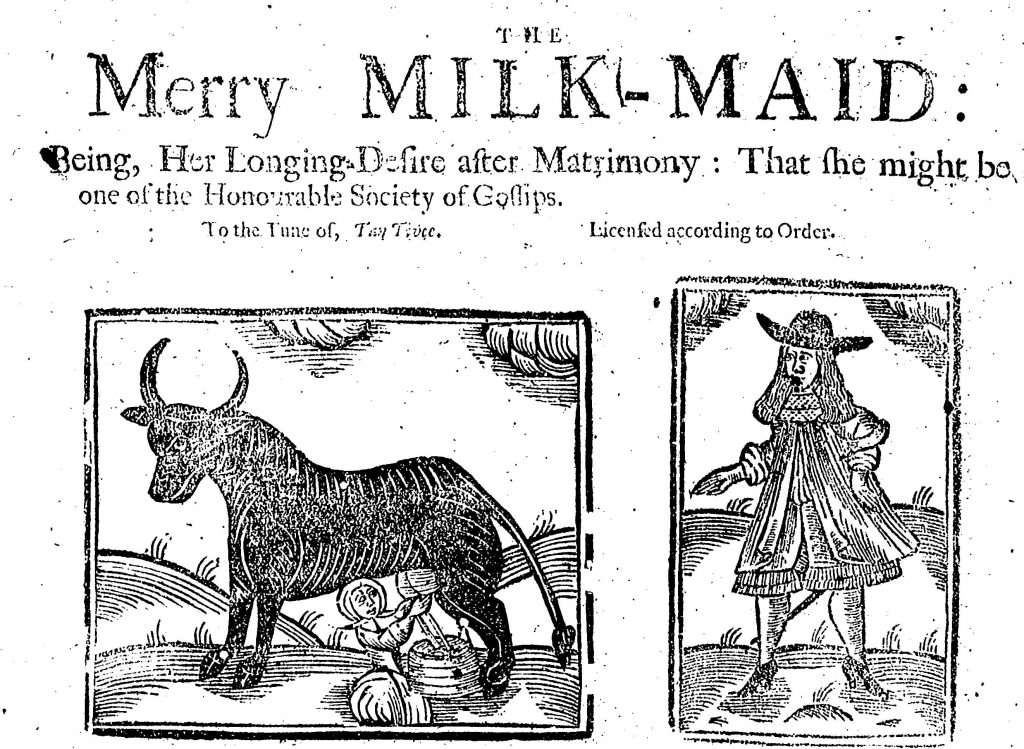

Fig. 4: Multi-species encounters and their broader cultural associations are an important part of the history of early modern posset, as this seventeenth-century pamphlet on “the merry milk-maid” shows (1690). Image credit: EEBO.

Sasha Handley: My fellowship at the library was funded by a major collaboration between the Folger Shakespeare Library and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation entitled Before ‘Farm to Table’: Early Modern Foodways and Cultures. The project uses the pervasiveness of food as a window into early modern culture. For me, this is absolutely about uncovering the importance of the tiny materialities of everyday life and the agentive force of foodstuffs, plants and herbs in shaping the physical and emotional dimensions of early modern lives. The material agency of foodstuffs, and the interlinked multispecies material world that underpinned foodways, was particularly powerful for early modern communities whose understanding of embodiment and subjectivity was so powerfully shaped by their entanglements with their physical surroundings. My research is still ongoing, but new and neo-materialist scholars such as Timothy J. LeCain, and posthumanist scholars such as Erica Fudge have certainly inspired me to pursue it.

Stefan Hanß: You have been recently awarded a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award for your new project on Sleeping Well in the Early Modern World: An Environmental Approach to the History of Sleep Care. Congratulations to this impressive achievement! Do you mind introducing this interview’s readers briefly to this project, and elaborating a bit more on how historians’ explorations of early modern microscopic records may benefit from environmental approaches to history? I assume that the insights gained from coevolutionary histories and new materialist approaches to the past are crucial here?

Sasha Handley: Thanks for your kind words about my Investigator Award, Stefan. This project will be the first to assess how people’s efforts to sleep well c.1500–1750 were influenced by a distinctive set of environmental relations and linked environing practices in which people engaged with their physical surroundings to optimise their sleep timings, bedding materials, and to prepare soporific tonics. We hope to reconstruct the principal agents, materials, and environing practices that were used to manage sleep in ecologically distinct parts of Britain, Ireland and England’s emergent American colonies of Virginia and Newfoundland, alongside the bodies of medical, botanical, climatic and material knowledge associated with them. The research is important because it brings a fresh environmental history perspective to bear upon cross-disciplinary debates about the significance that physical environments and non-human agents play/ed in shaping healthy and unhealthy sleep habits. The project will also assess the immediate and longer-term impacts of early modern processes of environmental change, such as the ‘little ice age’, in shaping people’s sleep care practices.

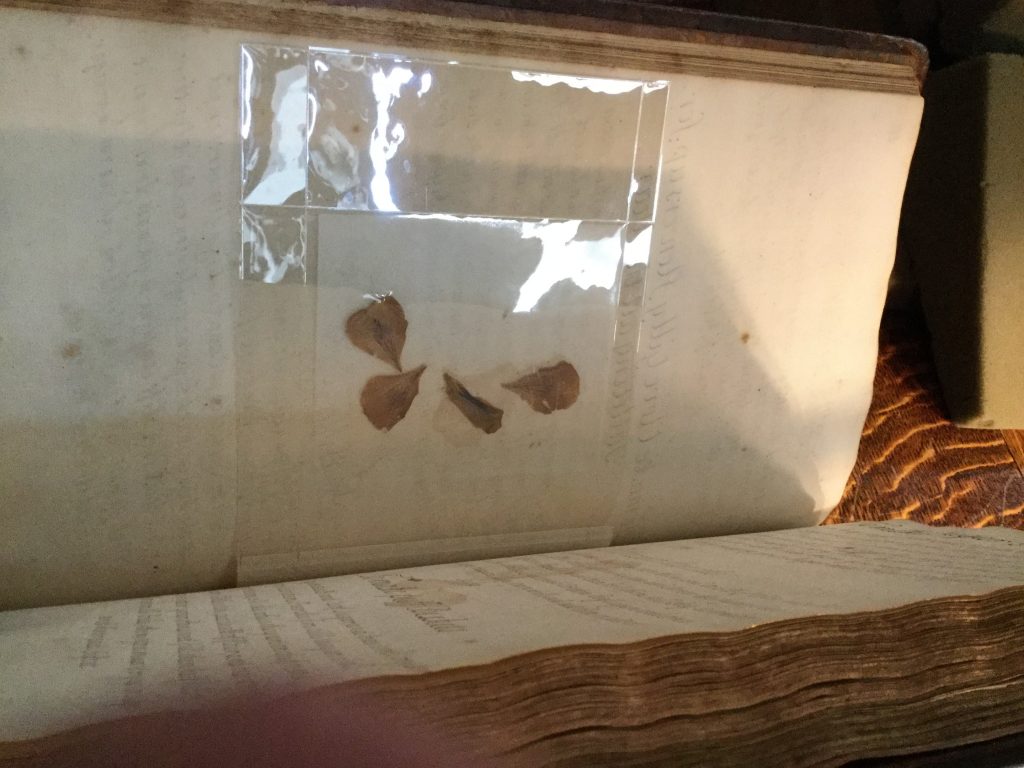

Fig. 5: Early modern recipe collections document small-scale material encounters: plant specimens preserved in an early modern English recipe collection. Image credit: Folger Shakespeare Library/Sasha Handley.

Sasha Handley: There are several ways in which the project might intersect with microscopic records. We will be analysing a range of surviving artefacts such as household textiles, window coverings, domestic ceramics, lighting technologies and carbonised food remains from the period to reconstruct the photic and thermal qualities of different sleep environments and to think about how sleep was managed through dietary practices. Many of these artefacts have been recovered in archaeological excavations and our assessment of them will be much more precise, detailed and persuasive if we can use microscopic technologies and methods to identify material qualities and likely provenances of those materials in local and/or global contexts. Similarly, we may be able to identify the flower petals and leaves that survive, for example, in some of the Folger Shakespeare Library’s recipe books (fig. 5), alongside the rich botanical literature of the period, to see if they have any relationship to the sleep remedies used in those collections. This will be particularly useful in helping us to construct a historic pharmacopoeia of soporifics. I hope that these investigations will build new connections between early modern social history, microscopy, and the exciting new field of plant humanities. Such an approach would undoubtedly sharpen our research conclusions and help us to better understand the nature, transformation and use of different plant species that were valued for their soporific qualities. Implicit within the project design is of course a strong emphasis on new materialist theories and co-evolutionary histories of plants, animals, humans and climatic influences.

Sasha Handley, The University of Manchester

Stefan Hanß, The University of Manchester

0 Comments