The 2020 US Presidential Campaign: Partisanship on Twitter

This US presidential election saw the emphasis on digital communication rise to an unprecedented level of prominence as rallies and in-person canvassing receded in the face of the pandemic. As such, we might expect to see campaigns switch to digital channels, although the question of which side might benefit most from this shift was not immediately clear. Certainly, Donald Trump was well-placed to communicate with the nation via social media given his campaign’s widely touted success in using Facebook advertising in 2016 and his own long-standing use of Twitter, very large followership, and apparent genius for crafting viral content. However, the traditionally more vocal nature of the left and the over-representation of those that disapprove of Trump within the Twittersphere (Pew, 2019a; Pew, 2019b), combined with rapid rise of Covid-19 on the national agenda during 2020, and likely use of social media by citizens to vent their frustration at Trump’s handling of the problem arguably granted Biden an opportunity to raise his profile and ‘out-Trump’ the President on his medium of choice. Here we investigate the salience and sentiment toward the two main candidates across the final four weeks of the campaign. Did Trump absorb the lion’s share of attention on Twitter? If not, how and when did Biden cut through and to what extent was this linked with a rise and fall of particular issues, most notably the question of Covid-19?

Method

In part 1 of this series of blog posts, we explain how we map the issue discussion on Twitter using YouGov survey data and Twitter data collected during the final four weeks of the campaign. In this post, to study the partisan nature of the campaign discourse, and the extent to which this discourse on Twitter favoured the Left, we use a dictionary that includes election-terms as keywords, as well as a dictionary with Twitter hashtags as keywords. We use the election-keywords to map the general prominence of references to Donald J. Trump, Joe Biden, the Democratic Party, and the Republican Party. Examples of these keywords are ‘The Donald’, ‘Biden’, ‘DNC’, and ‘RNC’. Thereafter, we identify hashtags which are neutral, in favour (‘pro’) or against (‘anti’) these actors, and we consider the prominence of these hashtags. Examples of these hashtags relating to Trump are #Trump2020ToSaveAmerica and #VoteTrumpOut. For Biden, example hashtags are #AmericaNeedsJoe and #CrookedJoeBiden. More information about our approach can be found in the methodological appendix.

Findings

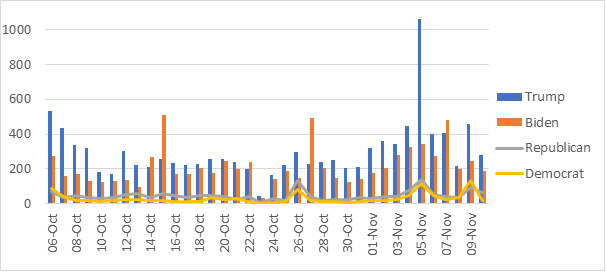

We first consider ‘neutral’ references to these four actors, to understand the extent to which these actors are talked about in Tweets, throughout the campaign. With a combined line and bar chart, Figure 1 shows the frequency of neutral references to these actors and the extent to which these fluctuate during the campaign.

Figure 1: References to the Two Candidates and Parties leading up to Election Day

Overall, Trump is referred to more frequently than Biden. Spikes in these references can be linked to campaign events and developments, which are reported and discussed on Twitter. For example, there is a major spike in references to Trump on November 5, which was when Trump continued to claim voter fraud, when two of his lawsuits, one relating to the handling of absentee ballots and the other to ballot counting, were dismissed and when he won a case about poll watching. Trump references spike again on November 9. This coincides with news about Trump’s vote certification lawsuit in Pennsylvania. In comparison, Biden is less frequently referred to. References to Biden hit a peak on October 15 and 27, and November 7. These peaks relate to his campaign activity: the ABC town hall (October 15), his first visit to swing state Georgia (October 27), and his predicted victory: when Pennsylvania was called, and the 270 electoral votes were reached (November 7). In comparison, there are considerably fewer references to both political parties. For both parties, there are three peaks in references. The first peak most likely relates to the confirmation of Barrett’s nomination to the Supreme Court (October 26). The second peak is likely connected to the lawsuit relating to Republican poll watchers, and to the criminal referral by the Nevada Republican Party to US Attorney General Barr alleging over 3,000 cases of voter fraud (both on November 5), as well as Biden’s leap in ballot counts (on November 5 and 6). Finally, the third peak in references to both parties could be linked to several developments, including: Trump’s vote certification lawsuit in Pennsylvania, the lack of access granted to Republican poll watchers, the refusal by Republican Raffensperger to step down, the professed victory of the Democratic Party and the transition, with Biden’s team contemplating to act against the GSA and Emily Murphy, a Republican herself.

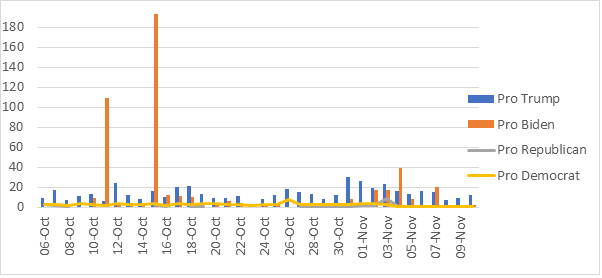

Next, we turn to positive and negative references to the two candidates and their parties. With a combined line and bar chart, Figure 2 shows the frequency of pro-hashtags and the extent to which these fluctuated during the campaign, and Figure 3 shows the frequency of anti-hashtags and their fluctuations.

Figure 2: Frequency of Pro-Hashtags referring to the Two Candidates and Parties

Figure 2 shows us that between October 6 and November 9, pro-hashtags for Trump are tweeted more frequently than pro-hashtags for Biden. The frequency of pro-Trump hashtags increases slightly on October 12, 17, 18 and 31 and November 3. These hashtags, which include #Trump2020, #MAGA, #MAGA2020, #americafirst, and #Trump2020LandslideVictory, correspond to his campaign activity: rallies in Florida, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Nevada (on October 12, 17 and 18) and rallies in Pennsylvania, Iowa, North Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Michigan, Wisconsin, and an illegal rally by Trump supporters in Downstate New York (between October 31 and November 3). Pro-Biden hashtags are less present throughout the campaign period, but there are major peaks on October 11 and 15, and November 4. This is when Biden is ahead of Trump in the polls (#biden2020, October 11), when Biden participates in an ABC Townhall (#BidenTownHall, October 15), and when the Associated Press declares Biden the projected winner of Arizona (#biden2020, November 4). Compared to the two candidates, pro-hashtags to the Democratic and Republican parties are used seldomly. Altogether, pro-hashtags for the Democratic Party are used more frequently than pro-hashtags for the Republican Party. There is a peak in the use of these pro-hashtags for the Democratic Party when Supreme Court Justice Barrett was confirmed (October 26), with hashtags such as #VoteBlueToEndThisNightmare and #voteblue. There is only a slight increase in pro-hashtags for the Republican Party on November 3, Election Day (with #votered used most frequently).

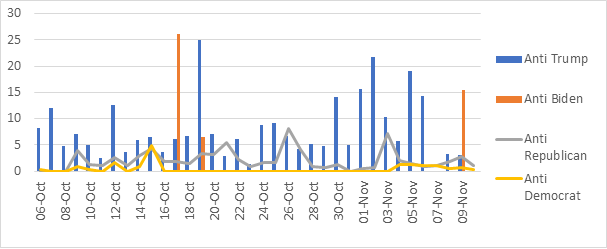

How about the use of anti-hashtags? Figure 3 tells us that anti-hashtags for Trump are tweeted more frequently than anti-hashtags for Biden. These anti-Trump hashtags also fluctuated more than the anti-hashtags for Biden.

Figure 3: Frequency of Anti-hashtags referring to the Two Candidates and Parties

Anti-Trump hashtags peak on October 19, and November 2 and 5. On October 19 and November 2 the #votehimout is trending, a slogan turned hashtag made popular by Hillary Clinton. The steep increase in anti-hashtags for Trump on November 5 is likely in response to Trump’s disapproval of the (legitimacy of the) election result. On this day, the anti-hashtags #TrumpIsALaughingStock, #TrumpIsLosing and #25thAmendmentNow are particularly prevalent. In contrast, anti-Biden hashtags are less prominent, and spike thrice. The first two peaks are on October 17 and 19. On these dates, #CrookedJoeBiden is frequently used, an anti-Biden hashtag that refers to Hunter Biden and his business dealings in Ukraine. On November 9, which is after Election Day, #sleepyjoe is frequently used instead. This is when opponents of Biden reflect on his victory. Meanwhile, the Republican Party is referred to more frequently referred to with anti-hashtags than the Democratic Party. These negative references to the Republican Party peak on October 9, 15, 21, 26 and 27, and November 3. These peaks in anti-hashtags that refer to the Republican Party are likely linked to the spread of COVID-19 after the Rose Garden Event (#RoseGardenMassacre, October 9), the Town Halls (#VoteBlueToEndThisNightmare, October 15), and news about Mitch McConnell (#DitchMitch and #MoscowMitch, frequently used on between October 21-27 and on November 3). In comparison, there are very few anti-hashtags that refer to the Democratic Party. There are peaks in anti-hashtags on October 12 and 15. On these days, #DemocratsAreCorrupt is frequently tweeted. Like #CrookedJoeBiden, this hashtag refers to Hunter Biden’s business dealings in Ukraine, but it is also used in Tweets about ‘ObamaBidenGate’, which was about the probe in the Republican role in Russia-collusion and the prosecution of Michael Flynn.

Discussion

In part 1 of this series of blog posts, we investigated which issues were most discussed on Twitter during the campaign. We found that the coronavirus pandemic, economy and law and order were the most important issues and that Twitter users and the general public have a common concern for these specific issues. In this second post, we further studied the idea that Twitter is used by specific users by focusing on the presence of partisanship on his platform. We do not find evidence that the Twitterverse was predominantly against Trump: instead, Trump receives considerably more attention on this platform than Joe Biden. In fact, few positive hashtags are frequently used to refer to Biden and following scandals relating to Hunter Biden and Russian collusion, there are only short-lasting spikes in anti-hashtags for Biden and the Democrats. These findings do not suggest that Twitter is left leaning or more pro-Democrat than pro-Republican. Instead, we find that Twitter served as a platform for Trump, his supporters, and his opponents.

References

Pew (2019a). Sizing up Twitter Users. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/04/24/sizing-up-twitter-users/

Pew (2019b). National Politics on Twitter: Small Share of U.S. Adults Produce Majority of Tweets. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/10/23/national-politics-on-twitter-small-share-of-u-s-adults-produce-majority-of-tweets/

0 Comments