Annual report 2019: England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales

Date of publication: December 2019

Our 2019 report provides findings relating to people who died by suicide in 2007-2017 across all UK countries. Additional findings are presented on the number of people convicted of homicide, and those under mental health care.

Our large and internationally unique database is a national case series of suicide by mental health patients over 20 years. This allows us to examine the circumstances surrounding these incidents and changes in trends over time, and to make recommendations for clinical practice and policy to improve safety locally, nationally, and internationally.

Key messages

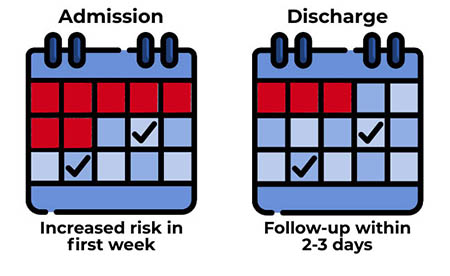

In-patient and post-discharge care

Our findings show that in-patient and post-discharge care remain times of high risk for suicide. We continue to recommend an emphasis on:

- safer wards, including removal of low-lying ligature points;

- awareness of increased risk within the 1st week of admission;

- comprehensive care planning for discharge and pre-discharge leave;

- follow-up within 2-3 days of discharge from in-patient care.

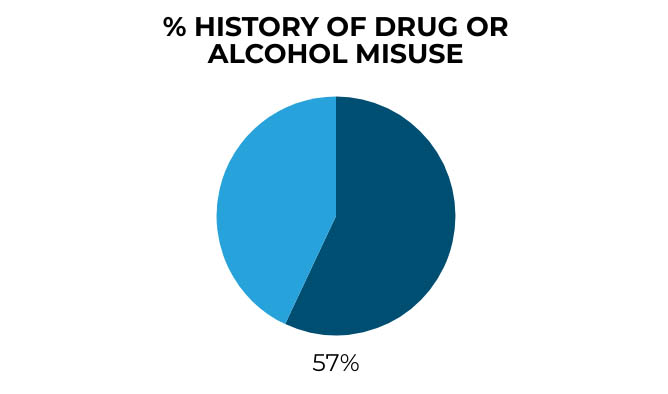

Alcohol and drug use

57% of patients who died by suicide in 2017 had a history of drug or alcohol misuse.

Clinical measures that could help reduce risk are:

- substance misuse assessment skills in frontline staff;

- specialist substance misuse clinicians within mental health services;

- joint working with local drug and alcohol services.

Methods of suicide

Reducing access to methods is one of the most effective ways to prevent suicide.

Services could take the following measures to reduce risk:

safer prescribing in primary and secondary care, particularly opiates/opioids prescribed to people with long-term physical illness;

safer prescribing in primary and secondary care, particularly opiates/opioids prescribed to people with long-term physical illness;

working with local authorities to reduce risk at frequently used locations, such as high places and railways;

working with local authorities to reduce risk at frequently used locations, such as high places and railways;

ensuring clinical staff are aware of suicide methods associated with internet use, as a result of information available online or by online purchase.

ensuring clinical staff are aware of suicide methods associated with internet use, as a result of information available online or by online purchase.

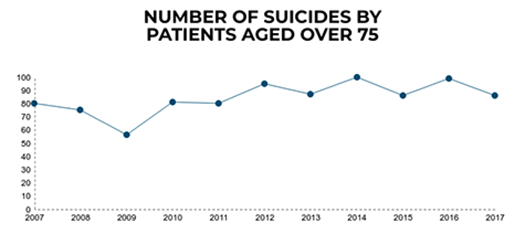

Patients aged 75 and over

During 2007-2017, the number of deaths in patients aged 75 and over in the UK increased, but the suicide rate (which takes into account the rising patient numbers) has fallen.

We ask clinical services to be aware of:

- the lower rate of contact with specialist mental health care in this age group and the need to work with other community services;

- different patterns of clinical risk, with more depression, bereavement and physical illness, and lower rates of self-harm and substance misuse.

Female patients under 25

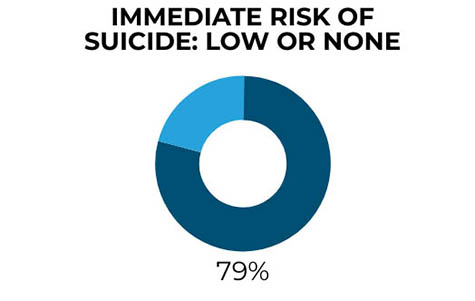

We have previously identified a distinct risk profile for female patients who died by suicide. Our findings now show the clinical complexity of young women who die by suicide was often not reflected in risk assessment, with the majority being seen as low risk.

We recommend that clinical services should:

- have the breadth of skills to respond to clinical complexity and comorbidities in this group, often including depression, a diagnosis of personality disorder, eating disorders, self-harm, and substance misuse;

- offer self-harm care that meets current quality standards;

- be aware of the recommendations of the Women’s Mental Health Taskforce report.

Homeless patients

There were 40 suicides per year in patients who were homeless, though this has been lower in the last three years. These patients were more often male and unemployed, and we found age-related differences – younger people with self-harm and substance misuse (including new psychoactive substances), and older men who were more likely to have depression and financial problems.

We suggest clinical services should be aware of:

- different patterns of risk among homeless patients;

- the need for specialist expertise in working with homeless people in areas where homelessness is a severe problem.

Patients with anxiety disorders

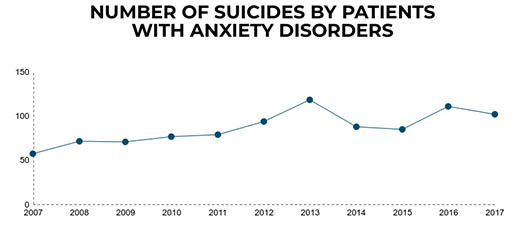

Our findings show the number of people who died by suicide with a primary diagnosis of anxiety disorder has risen – this might reflect a change in patterns of referral or diagnosis, or an increase in risk. Most were receiving drug treatment and around a third were taking benzodiazepines. A quarter were receiving some kind of psychological therapy and 8% were accessing Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services at the time of death.

We suggest measures to help suicide prevention in this group are:

- an awareness of the rise in suicide in patients with anxiety disorders, despite fewer conventional risk factors;

- reduced prescribing of benzodiazepines, and access to IAPT services.

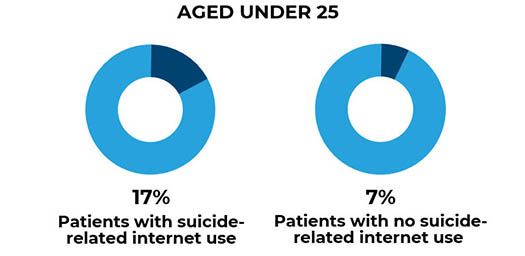

Internet risks

We found that the most common type of suicide-related internet use was searching for information about suicide method. The methods used by this group were different from other patients, with more deaths by gas inhalation and self-poisoning. Although they were more likely to be young, the patients in this group were diverse in age and diagnosis.

Clinicians need to be aware that:

- suicide-related internet use is a potential risk for all patients;

- there is a need to enquire about online behaviour as part of assessing risk.