Suicide by middle-aged men

Date of publication: May 2021

This report describes findings from a national study combining multiple sources of information to examine the factors related to suicide in middle-aged men. We collected data from a range of investigations into the deaths of men aged 40-54 by suicide (including probable suicide) in England, Scotland and Wales by official bodies, primarily coroner inquests (police death reports in Scotland).

This report is based on deaths that occurred in a 12-month period between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2017. It describes the antecedents of suicide and barriers to accessing services, and includes recommendations for suicide prevention for men in mid-life.

Key messages

Contact with services

Almost all (91%) middle-aged men had been in contact with at least one frontline service or agency, most often primary care services (82%). Half had been in contact with mental health services, 30% with the justice system.

Almost all (91%) middle-aged men had been in contact with at least one frontline service or agency, most often primary care services (82%). Half had been in contact with mental health services, 30% with the justice system.

It is therefore too simplistic to say men do not seek help. We should focus on how services can improve the recognition of risk and respond to men’s needs, and how services might work better together.

For the minority (9%) of men who we found to be out of contact with any supports, there are several examples of local and national third sector initiatives aiming to reach this group. We suggest these should be supported and adopted more widely.

Common antecedents of suicide

We found high rates of key risk factors compared to their incidence in the general population. 30% of men were unemployed, and a fifth (21%) were divorced or separated. Over a third (36%) reported a problem with alcohol misuse; 31% reported illicit drug use. Overall, 57% were experiencing economic problems – unemployment, finances or accommodation – at the time of death.

We found high rates of key risk factors compared to their incidence in the general population. 30% of men were unemployed, and a fifth (21%) were divorced or separated. Over a third (36%) reported a problem with alcohol misuse; 31% reported illicit drug use. Overall, 57% were experiencing economic problems – unemployment, finances or accommodation – at the time of death.

We suggest suicide prevention for men in mid-life requires a range of public health, clinical and socio-economic interventions.

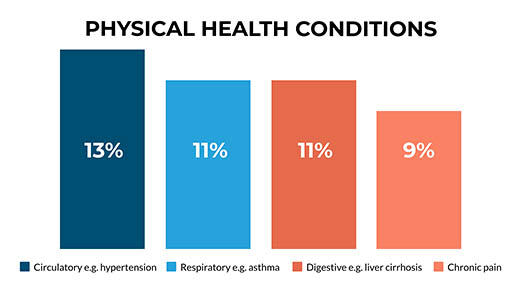

Physical health conditions

More than half (52%) of men who died had a physical health condition, most commonly circulatory system diseases, such as hypertension. We ask services to be aware of the importance of physical ill-health as a factor in suicide risk. We suggest that help-seeking for physical health problems may be an opportunity for prevention.

Psychological therapies

![]() A comparatively low rate (5%) of engagement with talking therapies was evident among the men we studied, despite the higher than expected rate of contact with services that we found. This is consistent with data showing women are twice as likely as men to finish a course of Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT), and are more likely than men to seek help through psychological therapy. We recommend psychological therapies suited to the needs of men should be offered.

A comparatively low rate (5%) of engagement with talking therapies was evident among the men we studied, despite the higher than expected rate of contact with services that we found. This is consistent with data showing women are twice as likely as men to finish a course of Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT), and are more likely than men to seek help through psychological therapy. We recommend psychological therapies suited to the needs of men should be offered.

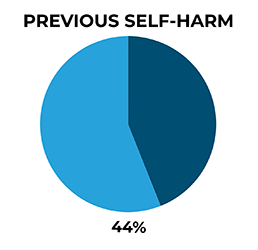

Self-harm

44% of men in mid-life who died by suicide had previously self-harmed, 7% in the week prior to death. We emphasise that recognition of risk by services after self-harm is vital, as further self-harm may involve a method of greater lethality such as hanging.

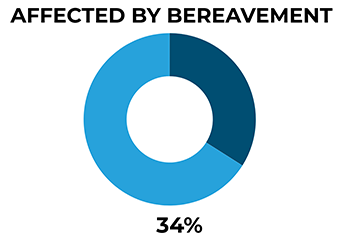

Bereavement

34% of men in our study appear to have been affected by bereavement, 6% by suicide bereavement. We suggest there is a need to ensure bereavement support is available in a way that addresses the needs of men.

Internet risks

We found 15% of men who died by suicide had used the internet in ways that were suicide-related, most often searching for information about suicide methods. We recommend online safety should be part of any prevention plan for men at risk of suicide.

We found 15% of men who died by suicide had used the internet in ways that were suicide-related, most often searching for information about suicide methods. We recommend online safety should be part of any prevention plan for men at risk of suicide.