Sowing the seeds of Muntú (part 2)

Sowing the seeds of Muntú to decode my Alphabet of a root-woman (part 2)

By Ashanti Dinah (Activist, Poet, Teacher, Researcher); translated by Peter Wade

I believe that literary criticism with Hispanic roots has to change the traditional theoretical and methodological tools used for the textual and discursive analysis of our cultural productions. Usually the ways of seeing and working of these instruments and devices start from universalist/universalizing categories and conceptual apparatuses applied to all literary artifacts from every region of the cosmos, nullifying any particularities. From an intellectual point of view, the normative effect of these trends has been to accentuate and consolidate a unidirectional vision, which serves as an anchor for ethnic biases.

Questions of racial democracy are still ignored or scarcely studied in the literary world of the continent; even our works continue not to be catalogued in bookstores and libraries; they remain unknown, unnoticed, delegitimised and not widely disseminated in cultural industries and publishing circles; we are not yet compulsory curricular reading in Latin American schools; conditions that favour equity in the literary field are still lacking. Even today we are not members of national language academies, because our presence in these institutions of power and knowledge, where the great majority are white-mestizo men, constitutes a kind of open wound of denied representativity.

Faced with aesthetic epistemicide and the menacing resurrection of doctrines of exclusion, persecution and death, which have wanted to keep us distant, scattered, silent; and in the face of the exoticization, demonization, infantilization and primitivism of black people in literature, we must undertake the task as Afro-descendant writers and writers to appeal to the vernacular Ubuntu concept of “I am because we are” as a non-Western philosophy, as a plural cosmopoetic, in the key of integrated good living (buen vivir). This discipline of knowing how to listen to the lessons of the grandmothers, who lacked the privilege and power of writing, was embodied by the Afro-Cuban poet Georgina Herrera (1936) in “Oriki para las negras viejas de antes” (“Oriki for the old black women of before”) in her poetry collection De Gatos y liebres o Libro de las conciliaciones (2009: Of Cats and Hares or Book of reconciliations). With the ancient wisdom of Obatalá, the collective I of maroon women, transformed into songbirds, working with a didactic vocation and with the sweat of the struggle on their backs, taught the pedagogy of life to the youngest women:

At funeral wakes / or at the time when sleep was the cloak / that covered the eyes, / they were like fabulous books opened / on golden pages. / The old black women, beak / of mysterious birds, Recounting as in songs what before / had reached their ears. / We were, without knowing it, owners / of all the hidden truth / in the depths of the earth. / But we, who now / should be them, were argumentative, / we didn’t know how to hear, / we took courses in Philosophy, / we didn’t believe. / We were born too close to another century. / We only learned to question everything / and, in the end, / we are without answers. / Now in the kitchen, on the patio, / anywhere, someone, / I’m sure, / expects us to tell what we should have learned. / We remain silent, / we seem sad / mute parakeets. / We did not know / how to seize the magic of telling / simply / because our ears were closed, / they were stubbornly deaf / before the grace of hearing.

If we start from the fact that the exercise of creativity is, and should be considered, a type of political participation, not to be underestimated, then writers are cultural agents of metamorphosis and renewal. Working against the denuding of collective memory, our commitment is to vindicate Afro humanism in order to achieve an organic reconnection with the fabric of life rooted in the land, through a polyphonic and ecological cosmovision of knowing and doing. Shoulder to shoulder, we must place ourselves on the side of organisational processes linked with social struggles and, therefore, on the side of the victims of racism, a racism that also disguises itself as theatre, which camouflages itself as a joke, that insults us with blackface, with that insolent laugh, tinged with blackness, that celebrates, rejoices and hurts us; it bruises our self-esteem, it makes us suffer in silence because “The rest of the world yearns to get back to normal. For black people, normal is the very thing from which we yearn to be free. […] Eventually, doctors will find a coronavirus vaccine, but black people will continue to wait, despite the futility of hope, for a cure for racism,” as described by the African-American writer of Haitian descent Roxane Gay in an opinion column in The New York Times.

As a counterpoint, we must give pride of place to shining examples of rebellion and insurgency as a way to reaffirm our identities, as the Afro-Cuban poet Nancy Morejón (b. 1944) does in her epic poem “Mujer negra” (1967, Black Woman), which tells of harassment, sexual abuse, and then the coming to consciousness of a captive woman who manages to escape to a palenque, an enclave of maroon settlement on the fringes of the institution of slavery, later joining the independence fighters of Afro-Cuban general Antonio Maceo (1845-1896):

I still smell the sea foam they made me go through. / The night, I can’t remember it. / Not even the ocean itself could remember it. / But I do not forget the first pelican I saw. / High, the clouds, like innocent eyewitnesses. / Perhaps I have forgotten neither my lost coastline, nor my ancestral language / They left me here and here I have lived. / And because I worked like an animal, / here I was born again. / How many Mandingan heroics did I try out / I rebelled. / Your / Grace bought me in a plaza. / I embroidered Your Grace’s coat and birthed you a male son. / My son did not have a name (…) I walked / This is the land where I suffered beatings whippings / and floggings / I rowed along all its rivers. / Under its sun I sowed, gathered and did not eat the harvests. / My home was a [slave] barracks. / I myself brought the stones to build it (…) I revolted (…) / I worked even more. / I made a better base for my millennial song and my hopes. / Here I built my world. / I went to the mountains. / My real independence was the palenque / and I rode among Maceo’s troops (…)

In a narrative couplet, in the poem that begins Rumbos (1993), entitled “Noble antílope, Benkos Bioho, ciudadano desnudo de la Guinea entera” (Noble Antelope, Benkos Bioho, Naked Citizen of All of Guinea) by the Afro-Caribbean writer Pedro Blas Julio Romero, from Getsemaní, Cartagena (b. 1949), the figure of Benkos Biohó, established as the founder of the routes of ma gende suto ri Palengue (Palenque de San Basilio), returns us to the site of marronage and the liberating role of our heroes:

From long ago I already knew about you, Benkos / since you seemed like a huge wind without speech / / a dull neighbourhood inside the dark noise / with your tongue beating out a drum solo of the lungs / The good winds began to arrive / into the warm summer of my room / you resided / in the gaze of my salty sadness / I understand that you were like another precious grandfather / a continuous thundering of the skin / birth of early rage / because a little – Mambo – were you still (…) Your orgasms / were hurricanes to guard Palenques / Benkos Biohó blackened commander among volcanoes / they were not lands of Canaan / but your kingdom in the sacrosanct mud / scorched mangrove of moving life / for your legendary throne of resistance / I still believe in you, beautiful monarch of the forbidden photo / in your milk is the height of all upright foliage / with your distant birds issuing blessed depositions / on the thickets of your heart / awash with jungle songs.

Today, we form a great powerhouse of anti-racist Afro-descendant writers, increasingly visible, aware of the social thinking and socio-ideological implications that derive from our literary works, all of which demands a profound redefinition of postponed identities, of aesthetics and of national literary canons. We are here, our emotions are heartfelt. Reworking in the plural the famous poem “And Still I Rise” by the African-American poet Maya Angelou (1928-2014), despite everything we collect together the fragments of our laments and raise up a howl in the shreds of our dreams:

You may write me down in history / With your bitter, twisted lies, / You may trod me in the very dirt / But still, like dust, I’ll rise. / Does my sassiness upset you? (…) ‘Cause I walk like I’ve got oil wells / Pumping in my living room. / Just like moons and like suns, (…) Still I’ll rise. / Did you want to see me broken? / Bowed head and lowered eyes? / Shoulders falling down like teardrops, / Weakened by my soulful cries? / Does my haughtiness offend you? / Don’t you take it awful hard / ‘Cause I laugh like I’ve got gold mines / Diggin’ in my own backyard. / You may shoot me with your words, / You may cut me with your eyes, / You may kill me with your hatefulness, / But still, like air, I’ll rise. (…) / Out of the huts of history’s shame / I rise / Up from a past that’s rooted in pain / I rise / I’m a black ocean, leaping and wide, / Welling and swelling I bear in the tide. / Leaving behind nights of terror and fear / I rise / Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear / I rise / Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave, / I am the dream and the hope of the slave. / I rise / I rise / I rise.

And while it is true that it hurts us a lot to utter the cry from the throat of our own reality, our pain also transmutes into community responsibility, into empowerment, participation and leadership, into strength, into food and spiritual energy. Cleansed by the incense of the word-action, the art of narrating from pain, from our emotional geography, from the pulse of our wombs united in the sacred waters of Yemayá, means to heal collectively the shared experience of the middle passage, implying a search for self-affirmation or radical autonomy rather than victimization. As a literary event, our writings about survival cannot be read as stories in baby letters that rock the cradle of the master’s estate.

For me, literature is “A weapon loaded with the future” [a poem by Gabriel Celaya], a terrain where nonconformity, political dispute and possible utopias are born. For me, the profession of writing, of putting time into poetry, has required lengthy encouragement, especially if we decide to reunite those fragments of African heritage scattered across centuries of sadness and loneliness. Which means that writing for me is an indispensable breath of air in the existential trenches of my belonging as a woman to the collectivity of descendants of the African Diaspora in Colombia, who were forged from silences and were born of denial and forgetting; and who have been defined by internalised perceptions of alterity, projected in the form of unlikeness.

From a transversal perspective, since poetry is an emotional, aesthetic, symbolic expression, I go beyond established conventions to fracture the predominantly white masculine canon imposed onto black literature. I write in pulses of blood:

I sense a priestess fashioned in Zarabanda. / I go deep into her woody rain / where the scented yam dwells. / She moves like an iguana fluttering through the silence, / like a witch summoned by the singing. / I sense a priestess fashioned in Zarabanda. / Waves of drums copulate in her navel. / Her dance fires up the great feast / on the reefs of the village. / I hear her shout out her secret through the drum: / Zarabanda, I call you / Zarabanda, I beg you / Zarabanda, you are the eye / Zarabanda, your malembe music / Zarabanda, you open the way / Zarabanda, your mayimbe music. / I sense a priestess fashioned in Zarabanda. / Black dawn, fire inside, shadow of hoe and machete, / strangler of roosters. / In the dark she wears the ritual / mask to officiate death. / No death throes will make her stop / her reptilian blood under the fireplace of the earth. / I sense a priestess fashioned in Zarabanda. / I keep her in my prayers, / I light her verse by verse, / I carry her in my cries. / Oh, nightfall of my soul! (“Ceremonia muertera” [Death ceremony] Ashanti Dinah)

On reencountering that planetary knowledge, pushed out by the hard shell of Western philosophy, I ask for Orisha Oko’s permission to plant a handful of pollen in the fauna and flora of my poetry and in the ethos of its ecosystems. Thus I not only pay tribute or make the gesture of moforibale, expressing gratitude to my ancestors, I also highlight the importance of the knowledge they received at birth through their navels, which witnessed the deep flow of the centuries and of “anonymous humanities”, and which still remain as dust in the purposeful forgetting of the tomes of official historiography:

I greet you my grandmother’s grandmother, / name of jungle or musical name of river. / Iron brand on the barracks of my shoulders. / Nocturnal motherland, / accomplice of stars, / From your curls hang constellations of feathers. / I am reflected in your bird-woman eyes / turned into a hum of leaves. / I pray to you with this creed of witches / with my forest tongue. / My healer, when I pronounce your name / my mouth fills with affection. / You are here looking out from the balcony of my memories, / in the calligraphy of my heart. / Proclamation of my enslaved African blood, / I caress the spirit of your uterus: / that terrace with the smell of lemon balm and sage, / rosemary and laurel / with hints of cassava and cane molasses. / I offer you my song so that you may run free / to iron out the wrinkles of sadness. / I thank you for accompanying my wanderings / and spreading sunlight on my roots. / I greet you, midwife of hope, / clairvoyant / tobacco smoker. / That at my dawn rebirth / eucalyptus and cinnamon may spring up alongside your fronds. / I ask you, guide my life map. / Today I dedicate to you my finest proclamations (“Tributo a mi tatarabuela” [Tribute to my great-great-grandmother], Ashanti Dinah)

Beyond the phonetic experiments of yambambó, yambambé (as in the poem by Nicolás Guillén), which belong to negrismo or the intellectual project of negritude, from my place of aesthetic enunciation, I assert ancestrality, I appropriate its subjectivities and its human condition in order to fill the “semantic voids”, to reverse the “dead signs” of the “other history of History” (with a hegemonic capital letter). I do not summon Hephaestus or Vulcan. I swim among the currents of my underground galleries. I unearth the silenced voices of the women healers, doctors and herbalists, of the midwives, the storytellers, guardians of knowledge: of the griots or the jalis (in the northern and southern areas of Mandê), of the guewel (in Wolof ), of the gawlo (in Fula), or of the akpalôs (in Nagô), because to ignite the volcanic lava of Aggayú and the bonfire hidden in my blood, I do not need permission from the Greek or Roman gods. I invoke the “Canto a changó, oricha fecundo” (Song to Changó, the fertile orisha) by Manuel Zapata Olivella (1920-2004), an Afro-Caribbean writer from Colombia:

Changó! / Voice forging thunder. / Hear, hear our voice! / Hear, hear our singing! / Hear the word of Muntu / without the thunder-light of your lightning. / Give me your saliva word / giver of light and death / shadow of the body / spark of life! / Hear, hear our voice! / The drum drowned in blood / speaks to the first parents! / Mighty Changó! / Breath of fire! / Brilliance of lightning! / Give me your thunder! / Fertile orisha, / mother of thought / dance / song / music / lend me your rhythm, / striking words, / let your drum voice settle here / your rhythm, your language! / Changó, your people are united in a single cry (…) / We do not weep, nor do we fear (…) / We just hope that you will keep us together / like the fingers of your hand. / Let your curse fall on our backs / Let a new flame be reborn in each wound, / But reveal to us, Changó, your tomorrow-face / showing where the unknown river of exile runs.

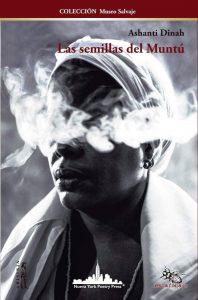

Indeed, in my book Las semillas del Muntú (The Seeds of Muntú) published by Escarabajo Editorial, Abisinia y Nueva York Poetry Press in 2019, the first of a trilogy, I embrace the legacy of Changó, el gran putas (1983), the epic of the Great Ekobio Zapata Olivella. With “cultural plasticity” (Rama, 1984: 38), through the category of Muntú, a term of Congo-Bantu origin for the principle of African humanity, I combine the ancient knowledge of African ecumenical philosophies (Congo-Bantu and Yoruba) in family coexistence with the egguns (the dead) and the dust from their bones; in connection with the ancestral sacredness of the Orishas of Santeria, with the Nkisis of Palo Monte and also with the loas, spirits of Voodoo, and their diagrams and word symbols drawn on the ground.

Both in my first collection of poems, and in the second, soon to be published, Alfabeto de una mujer raíz (2020, Alphabet of a Root Woman), my words are revealed, are politicised and cause a fracture, a paradigm shift in favour of decanonisation:

If you want strength in your blood, / season your spirit with panther. / Take root! / Nourish yourself with all sap in the forest. / Retrace the murmurs of the centuries, / plough through the afterglow of freedom in your body’s most solid part. / Feel the power of the roots / that keep watch over the time of the dead / in the flesh of the acacia trees. / Moisten yourself with the dance of the ivy / that hurries up your thighs. / Feel how the echo embraces / the sowing of your steps, / how the fish stretches / towards the bosom of the earth. / Rise and flourish like the sun / from pore to petal, from bark to stem. / The wind will know how to fly over your pollen / and awaken the long-awaited spring. / If you want answers, / look for them in the origins of the question. (“Raíz de África” [Root of Africa], Ashanti Dinah)

At the dawn of a new heroism, my black writing is a fire that conspires from within the crackling stoves, where Afro-diasporic words and thoughts simmer together. Its framework is a vehicle for re-existence, a necessary metaphor to choose the decolonising option in literature and aesthetic insubordination:

Mama Wanga has already said it: / “Let’s trust the wisdom of the universe, / its nature cannot be wrong. / If alchemy vibrates in our chest, / a rumour pulses within us, / a syllabary of bird calls, / a tender sprouting of wings. / Let’s awaken the voices / in the resinous saliva of the stars. / We are shepherds of the cosmos”. / We heard María Lionza say: / “Let us learn to read in the lines of the leaves / the memory of the roots. / A jump awaits us; / the heartbeat of the forest turns us a lemon green. / We are the sap in the veins of the tree”. / Mother Water advised us: / “Let us follow in the footsteps of the ancestors / when they reveal themselves through us / through the intuitions of the uterus. / Bird refuge where the sources of our power are deposited, / where fevers and the tide break out. / We are an intimate garden / full of mud and sacred marigolds”. / Mamá Chola predicted it long ago: / “We should let our waters settle, / it is vital to caress them, care for them with attention, / remove the dead leaves. / Let us care for their pains with aloe, / palo santo and cloves. / Let us offer them words, song and dance. / We are a ritual of aromas in the morning”. / Ma Francisca already told us, / “We must learn the mission / through the eyes / of a woman-spirit, / a woman-animal / half flight / half path. (“Las mujeres de la raíz” [The women of the root], Ashanti Dinah)

References cited

Angelou, Maya. 1978. And Still I Rise. Nueva York: Penguin Random House.

De Sousa Santos, Boaventura. 2009. Una epistemología del Sur. La reinvención del conocimiento y la emancipación social. México: CLACSO/ Siglo XXI.

García Márquez, Gabriel. 1970. Cien años de soledad. Barcelona: Círculo de Lectores.

Gay, Roxane. 2020. “Remember, No One Is Coming to Save Us.” The New York Times, May 30, 2020. https://nyti.ms/3gFDn0a.

Herrera, Georgina. 2009. De gatos y liebres o Libro de las conciliaciones. La Habana: Ediciones Unión.

Julio Romero, Pedro Blas. 2010. Obra poética Pedro Blas Julio Romero. Biblioteca de literatura afrocolombiana, tomo XIII. Bogotá: Ministerio de Cultura.

Mansour, Mónica. 1973. La poesía negrista. México: ERA.

Morejón, Nancy. 2002. Looking Within / Mirar Adentro: Selected Poems, 1954-2000. Bilingual edition edited by Juana M. Cordones-Cook. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Orozco Herrera, Dinah, 2009. Hacia una aproximación Sociocrítica: el sujeto afro- Caribe frente a la modernidad colombiana en la obra de Gabriel García Márquez. Tesis de Maestría. Bogotá, Instituto Caro y Cuervo.

Orozco Herrera, Dinah. 2019. Las semillas del Muntú. Bogotá, Buenos Aires, Nueva York: Escarabajo Editorial, Abisinia Editorial, Nueva York Poetry Press.

Orozco Herrera, Dinah. 2020. Alfabeto de una mujer raíz. Bogotá: Escarabajo Editorial.

Rama, Angel. 1984. Transculturación narrativa en América Latina. México: Siglo XXI.

van Dijk, Teun A. 1988. El discurso y la reproducción del racismo. Lenguaje en contexto (Universidad de Buenos Aires), 1(1-2): 131-180.

Zapata Olivella, Manuel. 2010. Changó, el gran putas. Bogotá: Biblioteca de literatura afrocolombiana. Ministerio de Cultura.

0 Comments